NAWA Luminaries – Janet Scudder (1869-1940)

NAWA Luminaries is the intersection of NAWA’s Historical Research and current events around the United States, highlighting celebrated NAWA members.

Graham Shay 1857, at 17 East 67th Street in New York, is exhibiting A Curated Selection of Twentieth Century American Paintings &Sculpture through August 30, 2024. Among the esteemed artists in the show are four historical members of NAWA: Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, Janet Scudder, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, and Anna Walinska. These artists have significantly contributed to the twentieth-century American art scene, and their works are a testament to their artistic prowess. The acclaimed sculptor Janet Scudder is the subject of this celebration of NAWA Luminaries.

NAWA Luminary Janet Scudder (1869-1940)

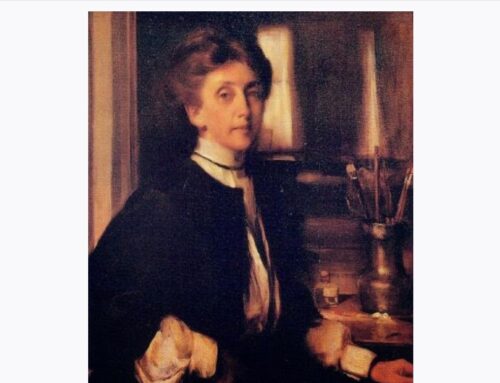

Janet Scudder. George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Digital File Number: LC-DIG-ggbain-15199)

American sculptor and painter Janet Scudder was best known for her memorial sculptures, bas-relief portraiture, portrait medallions, and garden sculptures and fountains. She was born Netta Deweze Frazee Scudder on October 27, 1869, in Terre Haute, Indiana, to Mary (Sparks) and William Hollingshead Scudder. She was called Nettie” by her family and was the fifth of seven children in a family marred by tragedy. Her mother died at the age of thirty-eight when she was five years old, and four of her six siblings died before they reached adulthood. Scudder’s father, a blind grandmother, and Hannah Hussey, the family maid, cook, and housekeeper, raised the surviving children. Her father subsequently remarried a woman Scudder notably disliked.

When, as a child, Scudder’s beloved grandmother gave her two illustrated volumes of Longfellow’s poetry, Scudder was not particularly interested in the poetry, but she did enjoy copying the illustrations. While attending Terre Haute public schools, Scudder developed her artistic talents in Saturday art classes at Rose Polytechnic Institute of Technology (the present-day Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology) under the direction of Professor William Ames. After graduating from Terre Haute High School in 1887, she enrolled at the Cincinnati Art Academy. When a teacher made an issue out of her unusual name, Scudder experimented with several alternatives before changing her name to Janet Scudder. At Cincinnati, she studied sculpture with Italian-born sculptor Louis Rebisso and decorative design, woodcarving, and painting.

In 1888–89, Scudder returned home to Terre Haute when the family suffered a series of hardships: the death of one of her brothers, the failure of her father’s business, and her father’s death in 1888. To help with household expenses, twenty-year-old Scudder taught woodcarving at a local school, Coates College for Women. Her older brother paid for her return to Cincinnati in 1890 to complete her studies at the academy. In 1891, Scudder moved to Chicago to live with her brother and his family while she attended classes at the Art Institute of Chicago under the direction of John Vanderpoel and Frederick Freer. She intended to earn a living as a wood carver and briefly worked in a furniture factory that created architectural decorations. Despite her skill and success, the workers’ union coerced her to quit when they made it clear that they would not accept women members.

Scudder found that other people were willing to hire a woman with her abilities. Chicago was preparing for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, and sculptor Lorado Taft, one of Scudder’s teachers, took her as an assistant despite her evident limited experience. When Daniel Burnham, the chief architect of the fair, told Lorado to hire assistants to help with additional work, Lorado was concerned he would not be allowed to hire women. Burnham, in response, told him he could employ “anyone who could do the work … white rabbits if they will help out.” Scudder became one of a group of women known as Taft’s “white rabbits,” who assisted him in enlarging sculptures from scaled models. Two other women in this group would also emerge as leading women sculptors and future NAWA members: Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1920) and Enid Yandell (1924)

The exposition proved to be an important incident for Scudder. With Taft’s help, she secured a commission to create a statue of Justice for the exposition’s Illinois building and the Nymph of Wabash for the Indiana building. She was enthralled by the beauty of Frederick MacMonnies’ monumental fountain in the Court of Honor. Although MacMonnies was supervising the installation, she was too shy to approach him. She decided that she had to study with him, and after the exposition, in late 1893, she traveled to Paris with Taft’s sister Zulime with a letter of introduction to MacMonnies. Initially rebuffed by him, she was persuasive enough to become one of his life drawing and modeling students while taking classes at the Académie Vitti and studying drawing with painter Luc-Olivier Merson at the Académie Colarossi. At age twenty-five, Scudder was the first woman MacMonnies employed at his atelier.

Her work experience with MacMonnies included modeling in low relief, a skill she would later employ in her medallion work. Their professional relationship was cut prematurely short because of the jealousy of another MacMonnies assistant, who convinced Scudder that MacMonnies was unhappy with her work. Uncomfortable discussing the matter with him, Scudder left for New York in 1894. Years later, she learned the competitive student had lied and that MacMonnies, who regarded Scudder as his finest assistant, had been hurt and puzzled by her abrupt departure.

In New York, Scudder lived in poverty until Silas Brownell, the wealthy father of fellow art student Matilda Auchincloss Brownell, used his influence to get Scudder a commission designing the seal of the New York Bar Association. The $750.00 she received to create the seal gave her enough funds to secure a respectable residence in the city. The project also led to opportunities for steady work making plaques, portrait medallions, architectural ornamentation, funerary urns, and sculpting.

Scudder returned to Paris in 1898, eager for more training at the Académie Colarossi. Accompanied by Matilda Brownell and Brownell’s maid and aided financially by Matilda’s father, the three women spent several years living in a home in Paris’s Montparnasse neighborhood. In her autobiography, Modeling My Life, Scudder identifies those three years as “the most important in my career as an artist. It was during that time that I found myself.” MacMonnies would visit her studio regularly and arranged to have her work placed at the Musée du Luxembourg, where she succeeded in selling several of her medallions. Scudder was thrilled having her work in the museum and considered it the “greatest honor any living artist can have,”3 Scudder would comment that MacMonnies “might just as well have asked me if I wanted to go to heaven when I died. Nothing could possibly have given me so much inspiring encouragement. Some people insist that an artist can get along without an occasional bouquet; that just working in an artistic direction is enough. I don’t agree with such statements. I believe we’ve got to have encouragement–just as we’ve got to have food.”4 Her first Salon appearance came in 1899 at the Salon des Artistes Français, where she exhibited a plaster bas-relief portrait in the sculpture section and a bronze medallion in the decorative arts section.

Scudder and Brownell spent the winter of 1899–1900 in Italy, where Scudder found fresh inspiration in Florence’s ornamental fountain statuary and Italian Renaissance sculpture. It was when she first saw works by Donatello and Andrea del Verrocchio. Scudder found what she wanted to do; a visit to Pompeii crystalized her intent: she filled her sketchbook with lighthearted pagan figures and decided never to do “stupid, solemn, self-righteous sculpture—even if I had to die in a poorhouse. My work should please and amuse the world. My work was going to decorate spots, make people feel cheerful and gay—nothing more!” She had settled on designing fountains for gardens, courtyards, and terraces. Returning to Paris, she began making sculptures and fountains featuring lively children, which she called her “water babies.” She was among the women artists invited to represent the United States at the 1900 Exposition Universelle at the Grand Palais. She created a decorative panel with an allegorical figure entitled Music. Scudder attributed its lack of success to her Italian model, who returned to work with an enlarged figure after taking a break to travel to Italy.

Scudder would continue to exhibit regularly at the Paris Salons. Her Frog Fountain (1901), a figure of a young boy looking down upon frogs, launched her career as a prolific and successful maker of ornamental garden fountains and sculptures. Scudder brought Frog Fountain to New York City, where architect Stanford White bought a bronzed cast for his estate on Long Island. Scudder produced five versions of this fountain, with the last one made for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. One of the other bronze versions of the Frog Fountain was created for a garden in the eastern United States and presented to the Woman’s Department Club of Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1928. It now resides in the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Scudder created other versions of garden fountains, most notably Tortoise Fountain (1908) and Young Diana, the latter of which earned an honorable mention at the Salon of Paris of 1911. Stanford White, who became her close friend, regularly ordered sculptures from Scudder until he died in 1906. She created at least thirty fountains as commissions for the homes of wealthy Americans. These included Piping Pan (1911) for John D. Rockefeller and Shell Fountain (1913) for Edith Rockefeller McCormick. American sculptor Malvina Hoffman arrived in Paris around 1910 and worked as Scudder’s studio assistant.

Scudder’s first solo show was in 1913 at Theodore B. Starr Galleries in New York City, and she became a National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors member (former name of NAWA) along with Malvina Hoffman the following year. Sculpture wasn’t Scudder’s only passion. She was a feminist who frequently marched in parades and demonstrations on women’s issues, and in 1915, she became involved in the women’s suffrage movement in New York. As a New York State Woman Suffrage Association member, she participated in the 1915 “Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture by Women Artists for the Benefit of the Women’s Suffrage Campaign” in New York.

Scudder opposed separate exhibitions for male and female artists and disliked the separate sex and gender references used to describe them, hoping for a time when artists were identified by their artistic accomplishments. Scudder wore pants while working in her studio, which was a bold act for a woman then. Her attire was highlighted in a 1912 Vogue article about American women artists in the Paris Salons: “As she descended from her ladder to greet me, she apologized laughingly for the absence of a skirt in her attire, declaring that experience had taught her the uselessness of such a garment in her profession. …[She] now wears a trim costume which, with her unworn face, slender figure, long step, and swinging gait, makes her more than ever resemble a boy.”1

A frequent traveler between New York and France, Scudder maintained art studios in New York City and Paris but preferred to live in Paris, where her social circle grew to include Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Mildrid Aldrich, and Eva Mudocci. In 1913, Scudder purchased a home at Ville d’Avray on the outskirts of Paris and made it her primary residence for several years.

Photo of Janet Scudder’s “Piping Pan,” c. 1916. The photo represents a sculpture commissioned by J. D. Rockefeller in 1911. Library of Congress, photographic prints 1910-1920

During World War I, she returned to New York to help organize the Lafayette Fund, which raised money to aid French soldiers. Her volunteer work did not keep her from her studio, and in 1915, she exhibited ten pieces at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, where she won a silver medal. When the United States entered the war, she returned to France, working first with the National War Work Council of the YMCA with the singer Camille Lane as entertainers for wounded soldiers, touring France from camp to camp. Lane sang, and Scudder worked as her manager. In 1918, they continued their tour for the American Red Cross. Scudder turned her house in Ville d’Avray over to the Red Cross for use as a military hospital and leased the organization her Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs studio, where American artists Anna Ladd and NAWA member Jane Poupelet (1914) fashioned portrait masks to aid wounded and disfigured soldiers. After the armistice was declared in 1918, Scudder divided her time between her studios in New York and France, and in 1920, she was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design. For her efforts in wartime, the French government made Scudder a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1925 for her wartime service. The same year, her autobiography, Modeling My Life, was published, providing an animated, intimate view of her memoirs.

Her sculpture, Victory, or Feminine Victory or Femina Victrix, symbolized women’s contributions during World War I and served as a model for a proposed National Suffrage Monument in Washington, D.C. It won a $300 prize at the Hoosier Salon exhibition in her home state of Indiana in 1926 for Outstanding Piece of Sculpture. By the 1920s, Scudder’s sculptural forms had become more “reserved,” “rigid,” and “stylized,” in contrast to the “active, dynamic composition” of her earlier and best-known work.2

Scudder continued sculpting and exhibiting her work in the United States and Europe. She participated in the annual exhibitions of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (former name of NAWA) regularly through 1934 and at the Hoosier Salon in Indiana in 1927, 1933, and 1934. Her work was part of the sculpture event in the art competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics, the International Exposition (Paris) in 1937, and the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Scudder spent most of the last decade of her life in Paris, where she painted and continued to sculpt. When WWII began in 1939, she aided refugee children in France before her failing health forced her to permanently return to the United States with her companion, suffragist, lawyer, and children’s book author, Marion Cothren. They settled in New York and summered in Old Lyme, Connecticut, and Rockport, Massachusetts. Janet Scudder died of pneumonia in Rockport on June 9, 1940, at 70.

Scudder’s work is represented in collections in France and the United States at the Library of Congress, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Peabody Institute, Brookgreen Gardens, the Huntington Library, Art Gallery and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Indiana State Museum, the Indiana Historical Society, the Swope Art Museum, and the Richmond Art Museum.

Sources:

3,4https://archive.org/details/modelingmylife008762mbp/page/n9/mode/2up

https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/janet-scudder/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Janet-Scudder

Dearinger, David Bernard, ed. (2004). Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design: 1826-1925. Vol. 1. Manchester, Vermont: Hudson Hills Press.

1Friend, Margaret Alice. “American Women in the French Salons.” Vogue, vol. 40, no. 2, July 15, 1912, pp. 24-5, 52.

2James, Edward T., ed. (1971). Notable American Women 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University. pp. 252-53.

https://reidhall.globalcenters.columbia.edu/content/arc-studio-portrait-masks

https://reidhall.globalcenters.columbia.edu/content/janet-scudder-1869-1940

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janet_Scudder

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A , Ed.D. Co-Leader: NAWA Historical Research Team. Website

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889