NAWA Luminaries – Augusta Savage

Nawa Luminaries is the intersection of NAWA’s Historical Research and current events around the United States highlighting celebrated NAWA members.

Augusta Christine Savage

Augusta Savage Photo: African American Registry

Herstory, a comprehensive survey of work by NAWA Honorary VP Judy Chicago at the New Museum, closed on March 3, 2024. The exhibit, which spanned Chicago’s sixty-year career and encompassed the artist’s contributions across painting, sculpture, installations, drawing, textiles, photography, stained glass, needlework, and printmaking, also placed Chicago’s work in the context of work by other women artists across centuries. An installation entitled The City Of Ladies, an exhibition-within-an-exhibition, featured artworks and archival materials from over eighty artists, writers, and influential thinkers. Among the group of esteemed women were four other NAWA members: Rosa Bonheur, a member in 1899; Agnes Pelton, a member in 1918; Augusta Savage, a member in 1934; and Louise Nevelson, a member in 1953 and Honorary VP in 1984. Augusta Savage’s work, Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp), 1939, was a small sculpture in a glass case. It was curious enough for Mary Ahern and Elena Zelenina, the other NAWA members with me at the museum, to stop and consider the artist described in the notes posted on the wall. Although informative, the minimal background information did not satisfy our curious minds.

The spotlight is presently shining on Augusta Savage, whose life and work are the subject of Searching for Augusta Savage, a new film from American Masters Shorts.

Born Augusta Christine Fells on February 29, 1892, in Green Cove Springs, Florida, Augusta was the seventh of fourteen children of Cornelia and Edward Fells, a Methodist minister. Her father did not appreciate the talent manifest in Augusta’s early clay figures. She would later recall that he almost whipped the art out of her.1

In 1907, fifteen-year-old Augusta dropped out of high school and married John T. Moore. Her daughter Irene was born the following year, and Moore died several years later. Seventeen-year-old Augusta and her young child moved back into Augusta’s family home. In 1915, Augusta’s father moved the family to West Palm Beach, Florida, where Augusta resumed her high school education. After high school, Augusta briefly attended two colleges: the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University for Negroes (FAMU) (now Florida A&M University) and Tallahassee State University. Her academic career did not last long; in 1915, she married a carpenter named James Savage. While they divorced after just a few months, Augusta kept his last name for the rest of her professional life.

Without encouragement from her family and local clay to work with, Augusta did not continue sculpting until 1919, when a local potter offered her some clay. She used the medium to create a group of figures and entered them into the West Palm Beach County Fair. When the sculptures won prizes, she was encouraged to give her career a go. She moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where she hoped to support herself by sculpting portrait busts of prominent blacks in the community. By 1921, the patronage had not materialized, and Augusta decided to leave her daughter in the care of her parents and move to New York City.

Augusta arrived in New York with $4.60 and found a job as an apartment caretaker. She had hoped to study at the School of American Sculpture, founded by the sculptor Solon Borglum, but she could not afford the tuition fees. Impressed by her work, Borglum wrote a letter of recommendation, and she was awarded a scholarship to Cooper Union School of Art, where she completed the four-year course in three years. Augusta married Robert L. Poston in 1923, only to be widowed the following year.

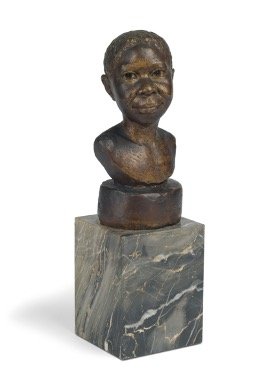

Gamin – 1929

The American sculptor George Brewster, well-known for his portrait busts and historical monuments, strongly influenced Augusta’s work at Cooper Union. Excelling, Augusta was one of 100 women who won a scholarship to study at France’s prestigious Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts. An American selection committee – the American Committee of Eminent American Architects, Painters, and Sculptors – comprised entirely of white men had identified the awardees. Learning that Augusta was Black, they rescinded her scholarship, noting that Southern white women could not be expected to share travel accommodations with a Black woman. Augusta engaged in an intense letter-writing campaign to bring attention to her situation and advocate for fair and unbiased treatment for future Black applicants. Her case was covered in both black and white newspapers across the country. Writing on Augusta’s behalf, the prominent civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois wrote letters to each committee member chastising them for their bigotry.

In the mid-1920s, the Harlem Renaissance was at its peak. Augusta lived and worked in a studio apartment, earning a reputation as a portrait sculptor, completing busts of W.E.B. Du Bois and the political activist Marcus Garvey. Augusta began exhibiting her sculptures throughout New York and received rave reviews. In September 1929, her bust of her nephew Ellis Ford, Gamin was featured on the cover of Opportunity, a literary magazine dedicated to Black culture, and seeing it, the Julius Rosenwald Fund offered Augusta a scholarship to study in Paris. In Paris, she lived in an apartment in Montparnasse, studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière (an institution already associated with Harlem Renaissance writers such as Claude McKay and Countee Cullen), and worked in the studio of one of her professors, the French sculptor Felix Benneteau-Desgrois. She also studied under sculptor Charles Despiau.

Augusta Savage

Head of a Young Girl-Martiniquaise

A French journal ran a cover story on Augusta, and three of her figurative works were exhibited at the Salon d’Automne. She also sent works to the United States for display; the Harmon Foundation exhibited Gamin in 1930 and Bust and The Chase (in palm wood) in 1931. That same year, Augusta won a gold medal for a piece at the Colonial Exposition and exhibited two female nudes (Nu in bronze and Martiniquaise in plaster) at the Société des Artistes Français. In addition, she successfully applied for a second Rosenwald scholarship and received a Carnegie Foundation grant, allowing her to remain in Europe for another year.

In 1932, upon returning from her fellowship in Paris, Augusta’s bust commissions were still in high demand despite the Great Depression. Augusta taught art at the Harlem Library to supplement the income from her commissions. She subsequently opened a studio, the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, in a basement on West 143rd Street, where African-American students could attend painting, drawing, and sculpting classes. With the Works Progress Administration (WPA) program, Augusta, with multidisciplinary artist Charles Alston and muralist Elba Lightfoot, established the Harlem Artists Guild and the Harlem Art Workshop in 1935. Successful with these initiatives, Augusta won further WPA funding, which she used to open the Harlem Community Art Center.

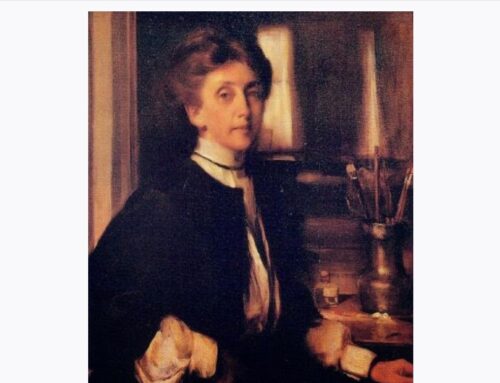

Augusta Savage became the first African-American member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors in 1934. Her sculptures, Martiniquaise and The Sage were included in the association’s annual exhibition in 1935.

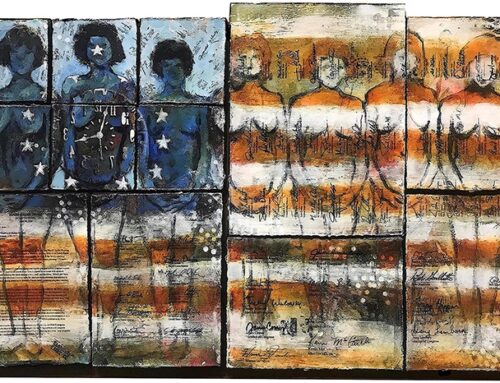

Augusta Savage-Lift Every Voice and Sing Photo: Public Domain

In 1937, she received a commission from the New York World’s Fair to create a sculpture for the International Exposition. She took a leave of absence from her position at the Harlem Community Art Center and spent almost two years completing the sixteen-foot sculpture. Her sculpture, Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp), featured a sixteen-foot-tall harp made of African-American figures. Cast in plaster and finished to resemble black basalt, The Harp was exhibited in the court of the Contemporary Arts building and became one of the most visited works at the Fair. The mouths of the figures were open wide as if they were singing, and the vertical folds of their choir robes were a visual simile of harp strings. At a forty-five-degree angle, a hand extending from the base cradles the figures was intended to represent “the hand of God.” At the front of the sculpture, a male African-American figure crouches, sheet music in hand. Augusta found inspiration from the 1900 poem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” written by her friend and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson and set to music as a hymn by his brother John Rosamond Johnson in 1905. The hymn would come to be known as the “Negro National Anthem.” After the fair closed, Augusta lacked the funds to store the critically acclaimed work or cast it in bronze. The sculpture was destroyed. The miniaturized version in the New Museum exhibition is among the versions that remain.

During the spring of 1939, Augusta held a small, one-woman show at NAWA’s Argent Gallery in New York. With her success motivating her, Augusta opened the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art, making her the first African-American woman to open her own gallery. Artists who exhibited there included Beauford Delaney, James Lesesne Wells, Lois Mailou Jones, and Richmond Barthe. Some 500 people attended the inaugural exhibition, and Savage announced, “We do not ask any special favors as artists because of our race. We only want to present to you our works and ask you to judge them on their merits.”2 Although the exhibitions were well-attended and well-received by critics, there were few sales, and the Salon closed within a few months.

Augusta Savage

Lift every voice and sing

Miniature version on view at the New Museum “City of Ladies” Exhibition 2024.

The gradual decline of Augusta’s career appeared to coincide with the failure of the Salon. At almost fifty, Augusta tried to make a living, but her financial situation did not improve by 1945, leaving her considerably depressed. She moved to a farmhouse in Saugerties, New York, and with the friends she made in the Catskill Mountains and the friends from the city who would come to visit, she made a life for herself raising pigeons and chickens. Interestingly, she also worked at the K-B Products Corporation as a laboratory assistant in the cancer research facility. The laboratory director, Herman K. Knaust, purchased art supplies for Augusta and encouraged her to create. She continued to produce her work in a converted garden studio and taught sculpting to children at summer camps. She also produced portrait busts for tourists and experimented with writing children’s books and murder mysteries, though none were ever published. When she was diagnosed with terminal cancer, she returned to New York City to live with her daughter Irene. Augusta passed away on March 27, 1962. In 2001, Augusta’s home and studio in Saugerties were placed on the New York State and National Register of Historic Places.

Sources:

1 Regenia A. Perry (1992). Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art in Association with Pomegranate Art Books, 1992.

2https://www.theartstory.org/artist/savage-augusta/

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/augusta-savage-4269

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/30/us/augusta-savage-black-woman-artist-harlem-renaissance.html

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A , Ed.D. Co-Leader: NAWA Historical Research Team

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889