NAWA Luminaries – Faith Ringgold (1930-2024)

NAWA Luminaries is the intersection of NAWA’s Historical Research and current events around the United States highlighting celebrated NAWA members.

Faith Ringgold

American painter, mixed media sculptor, performance artist, author, educator, and organizer perhaps best known for her quilts, Faith Ringgold was one of her generation’s most influential cultural figures. Faith drew from personal autobiography and collective histories for sixty years to document her life as an artist and mother and amplify the struggles for social justice and equity.” 1

Faith Ringgold was born Faith Willi Jones in Harlem Hospital in New York City on October 8, 1930, the third child of Willi (nee Posey), a fashion designer who had studied at the Fashion Institute of Technology, and Andrew Jones Sr, a minister, a driver for the sanitation department, and a powerful storyteller. Her parents came from families that had experienced the Great Migration, the relocation of millions of African Americans from the rural south to the urban north during the first half of the 20th century.

Growing up in Harlem during the Great Depression, Faith suffered from severe asthma and was homeschooled until age eight, after which she enrolled at Public School 90. The asthma often prevented her from attending school, and her mother encouraged her to pursue art and taught her how to sew and use patterns. Faith helped her mother with her fashion shows and became comfortable speaking before groups of people. Her grandmother taught Faith how to quilt and the importance of the African-American tradition in telling stories and creating community. Quilting was a family tradition; Faith’s grandmother had learned about art from her mother, Susie Shannon, a slave.

Faith’s early childhood occurred during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance and her neighborhood was home to many African-American artists, writers, and musicians, including Thurgood Marshall, Dinah Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, Aaron Douglass, and Duke Ellington. Thus, Faith grew up in an environment of vibrant creative possibilities, a strong sense of family and community, artistic practices connecting generations, and an awareness of segregation, racism, and economic inequities.

In 1950, Faith enrolled at New York’s City College, intending to study art, but, was denied entry into the exclusively male program. She was required to enroll in art education to study art. That same year, she married classical and jazz musician Robert Earl Wallace. The marriage ended in divorce four years later. The couple had two daughters, Michele Faith Wallace and Barbara Faith Wallace.

At City College, Faith studied with the artists Yasuo Koniyoshi and Robert Gwathmey and met Robert Blackburn, with whom she later collaborated. Faith graduated in 1955 with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art and Education and began teaching in the public school system in New York while working toward a Master of Fine Arts degree at City College and graduating in 1959.

Faith explored what it meant to be an African American artist and looked at African culture and the masks it produced. She was also influenced by the paintings of Jacob Lawrence, who was known for portraying African-American historical subjects and contemporary life in Harlem. Finding it difficult as an African American woman artist to find gallery representation for her work, Faith had an art-changing conversation in 1963 with Ruth White, who ran a gallery in NY. White refused to show Faith’s still life and landscapes, and Faith explained to her husband, Burdette Ringgold, whom she had married in 1962, that White’s advice had been to tell her story, and it had to come out of her life, her environment, who she was and where she came from.

Faith began painting the American People Series. In 1967, an invitation from Robert Newman for a solo show at his co-op gallery Spectrum energized Faith, and Newman allowed her to use the gallery space as a studio while it was closed for the summer. Faith had time and space free of familial obligations to create significant works. The Black Light Series followed, and these two series, according to Neuberger Museum of Art’s Tracy Fitzpatrick, informed everything she subsequently developed.2

Faith’s work met with an indifferent response from the art world. It was inappropriate to do political art during the 1960s, even though everything else was political. Challenged to overcome this obstacle, she became an activist for feminist and anti-racism causes, co-founding the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee with art critic and historian Lucy Lippard and artist Poppy Johnson to protest an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1968. No women and no African American artists were included in the show. To protest, the group left eggs in the Whitney, and Faith came up with the idea of each member blowing a whistle to disrupt the show. Subsequently, Faith co-founded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation, the National Black Feminist Organization, and “Where We At” Black Women Artists. In the early 1970s, she painted a mural For the Women’s House as a permanent installation at the Women’s House of Detention on Riker’s Island. As a result, Art Without Walls, an organization that brings art to prison populations, was founded.

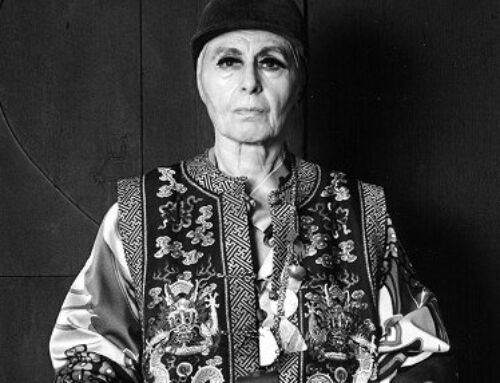

In the early 1970s, Faith’s work moved away from traditional painting as she began using fabric and experimenting with soft sculpture. Influenced by the traditional Western African use of masks, she painted linen and created costumes to which she added beads, raffia hair, and painted gourds for breasts. Each work represented a spiritual and sculptural identity. Intending the pieces in her Witch Mask Series to be worn and not merely displayed as art objects, she developed her first performance piece, The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro. This narrative dealt with the effects of slavery and drug addiction in the African American community. Faith’s Family of Woman Mask Series continued her work in mask costumes. She also created a life-size soft sculpture portrait of NBA basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain, who had made negative comments about African American women.

After a 1972 visit to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, where Faith saw an exhibit of Buddhist paintings on cloth scrolls, known as thangkas, she was inspired to add fabric borders to her paintings. In her Slave Rape Series of 1983, which focused on the slave trade viewed from the experience of an African woman taken into slavery, Faith incorporated the African American tradition of quilt making, and in 1980, working with her mother created Echoes of Harlem, which depicted 30 local residents. Using quilts, Faith could tell stories by combining images with handwritten texts. The narratives focused on a character, sometimes drawn from cultural history, such as in Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) and sometimes autobiographical, such as in Tar Beach or Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pounds Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt, both from 1986.

The 1980s offered more expansive opportunities. Faith began teaching art at the University of California, San Diego, in 1987, a position she held until she retired as professor emeritus in 2002. After seeing Tar Beach, her story quilt, a publisher expressed interest in Faith turning the story quilt into a children’s book. Tar Beach appeared in 1991 and launched Faith’s career as an author of award-winning children’s books based on the stories and images of her art projects.

Her style continued to evolve in the 1990s as she was influenced by the colors and repetitive imagery of Abstract Expressionism and Pop art. She began appliqueing, sewing fabric onto the canvas, and photo-etching. In 2000, she began silkscreen printing on pieces that used text on fabric borders.

Faith Ringgold, Self Portrait, 2023, Signed and dated screenprint 28 x 23″ Edition 98 of 100

Faith reached larger audiences in later years with her 2010 People Portraits, a series of 52 mosaics installed in the Civic Center subway station in Los Angeles. In 2014, she created the billboard Groovin High as an installation piece for the High Line’s train stop at 18th Street and 10th Avenue in New York. Faith’s work as an artist has gradually received more attention from the art world. ‘American People, Black Light: Faith’s Paintings of the 1960s’ was the first comprehensive showing of her work at the Neuberger Museum of Art in 2010. The exhibit was also at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in 2013. “Faith Ringgold: American People,” a retrospective at the New Museum in 2022, provided a comprehensive assessment of her impactful vision. Faith, an Honorary Vice President of NAWA, participated in NAWA’s exhibition at Hollis Taggart Gallery in March 2024, part of the 135th Anniversary celebration. Honored by the National Arts Club, Faith received over 80 awards and honors and 23 Honorary Doctorates. Faith died Friday, April 12, 2024, at 93.

Sources:

1 https://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/faith-ringgold-american-people

2https://www.theartstory.org/artist/ringgold-faith

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2024/apr/19/faith-ringgold-obituary

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A , Ed.D. Co-Leader: NAWA Historical Research Team. Website.

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889