NAWA Luminaries – Ethel Kremer Schwabacher.

NAWA Luminaries is the intersection of the National Association of Women Artists’ historical research and current exhibitions around the United States highlighting celebrated NAWA members.

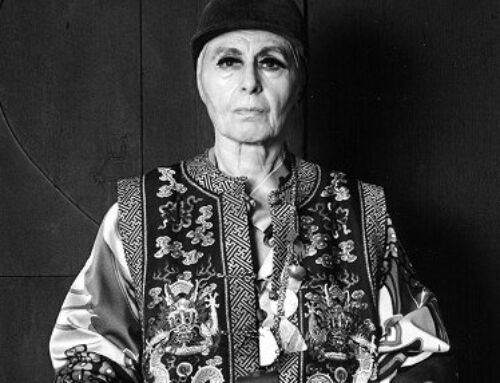

Ethel Schwabacher (ca. 1920s). Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

Ethel Kremer Schwabacher

by Susan M. Rostan, MFA. EdD. NAWA Historian

“..art was always a question of bringing near-nothingness to something. Out of a blank piece of paper, out of a few insignificant materials and the thought of the artist came productions, productions that awoke thoughts and feelings, productions that had meanings…. It is..an expression of joy giving, it gives back something that was frequently hidden from the individual –his power of feeling, the power of feeling the beautiful, his deep involvement in it.” Ethel Kremer Schwabacher, October 12, 1979

The painting first seized my attention when Berry Campbell Gallery’s 2024 “Perseverance” exhibition flashed across my iPhone screen—just a partial image, but enough to stop my scrolling. The exhibition celebrated women artists spanning multiple generations, and among these works stood a commanding 1959 painting titled “Prometheus.” The bold, energetic brushwork and vibrant color choices struck a deep chord with my artistic sensibilities. Intrigued, I began searching for the artist and digging into her background and artistic journey, only to uncover a fascinating detail: she had become a member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (NAWA) in 1926 when she was just twenty-three and then known as Ethel Kremer.

Like many historical National Association of Women Artists (NAWA) members, Ethel Kremer Schwabacher achieved significant recognition during her lifetime, later overlooked by art history. Though not officially part of the Abstract Expressionist movement, she was deeply embedded in New York’s art world from the 1940s through the 1960s. As a student and close friend of Arshile Gorky, she maintained strong connections with leading artists, including Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman. The prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery, a primary venue for avant-garde art, represented her work, hosting five solo exhibitions and including her in fourteen group shows. Beyond her achievements in painting, Schwabacher distinguished herself as a writer. Her 1957 biography of Gorky offered unique artist-to-artist insights, particularly emphasizing his Surrealist influence on Abstract Expressionism. She continued her literary contributions with other works, including a 1974 book on John Charles Ford.

Ethel Kremer was born in New York on May 20, 1903, to Eugene George and Agnes (née Oppenheimer) Kremer and grew up in a privileged and creative environment. When the Kremer family moved to Pelham, New York, in 1908, Ethel attended the experimental and developmental unit of Teachers College, the Horace Mann School in Riverdale. Ethel began painting and keeping a journal at an early age when her first painting experiments captured the flora and foliage in the garden of her family’s home. In 1918, at age 15 and in high school, Ethel enrolled at the Art Students League. She studied briefly with the Canadian American painter and anatomy and figure drawing teacher George Bridgman and the French American modernist figural sculptor Robert Laurent, with whom she continued studying until 1927. Intending to become a sculptor, she studied sculpture with Brenda Putnam and Georg J. Lober, both figural sculptors.

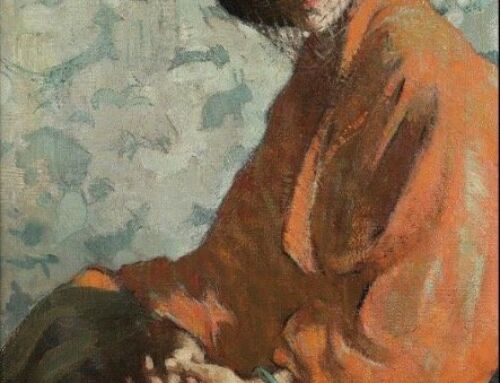

Ethel Schwabacher, Return No. 3, 1957, Oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches, © Estate of Ethel Schwabacher. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

After losing her father in 1920 and graduating from Horace Mann, she spent a year at the National Academy of Design, followed by an apprenticeship with the Piccirilli brothers, an Italian family of renowned marble carvers and sculptors. In 1923, she began dating Mortimer J. Adler, a Columbia student who later pioneered the great-books curriculum. She studied under sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington that summer but found the encouraged focus on horses disconnected from her growing interest in women artists’ issues. Thus, she joined The National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors in 1926.

1927 brought multiple crises for Schwabacher: lingering grief over her father’s death, a breakup with Adler, an overprotective widowed mother, her brother’s mental health struggles, and falling in love with her analyst, Bernard Glueck. Unable to cope, Ethel attempted suicide. When she recovered, she decided to abandon sculpture for painting and studied under Max Weber at the Art Students League. It was at this time in her life that Ethel met Arshile Gorky. Deciding that she needed to travel, Ethel spent time in Europe, where she studied painting in the South of France, and then Vienna, where she underwent psychoanalysis with Helene Deutsch, a Freud protégé specializing in women. Upon returning to the US in 1934, she began private lessons with Gorky, who was not then well-known, alongside Mina Boehm Metzger at his Union Square studio.

During her studies with Gorky, who was blending Cubism and Surrealism while also creating figural works, Ethel developed a style influenced by Matisse, Cézanne, and Cubism. Drawing inspiration from Gorky’s biomorphic abstractions and automatism technique, she began creating nature-inspired abstract forms that incorporated insights from her experiences in psychoanalysis.

Ethel married Wolfgang Schwabacher, a lawyer representing creative clients, including Gorky, in 1935. During their nurturing marriage, they had two children: Brenda in 1936 and Christopher in 1941, the year Ethel was featured in a group exhibition at the Georgette Passedoit Gallery in New York. Through the 1940s, she developed a spontaneous abstract style rooted in childhood memories and nature, creating images in which archetypal forms emerged. Ethel also referenced women’s issues in her art, incorporating a photograph of a “girl guerilla fighter” milking a cow captured from the enemy as the basis for several works. She helped care for Gorky after his cancer diagnosis in 1946 and planned to write Gorky’s biography with his wife, Agnes. After his suicide in 1948, Ethel temporarily shelved the project.

Schwabacher’s first solo show at Passedoit Gallery in 1947 featured works with quotes from D.H. Lawrence and the Hebrew Bible as titles. In the catalog’s foreword, Schwabacher wrote that she had struggled to find “a rhythm in style which would be the rhythm of a living thing, “1 an achievement noted in Artnews2.

Between 1949 and 1963, Ethel regularly exhibited at Whitney Museum annuals. In 1951, she wrote a commentary for Gorky’s memorial exhibition at the Whitney3. Ethel began her Women series at that time, exploring themes of fertility and feminine experience, composing forms of women’s bodies, fetuses, and emblems of female fertility. That same year, her husband Wolf’s sudden death at fifty-three led to a period of intense grief, during which she converted her apartment into a studio and created her Odes series while listening to loud classical music. The topics of loss, anxiety, loneliness, and separation permeated her work, and Ethel attempted suicide again in 1952. Recovering from the resultant coma, Ethel began painting again along with psychoanalysis with Dr. Marianne Kris.

In 1953, Ethel had a solo exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, comprised of paintings created between 1951 and 1953, her Woman, Ode, and City series. The abstract works expressed her traumas, remembered experiences and fears interpreted through Greek myths.. Art historian Lloyd Goodrich praised her in the catalog as a “sensitive” artist whose work conveyed both “lyric rapture” and “tragic emotion.”4 Howard Devree’s New York Times review pointed to her Gorky-like style.5.

Ethel was featured in a show of ten women artists sponsored by the National Council of Women of the United States at the Riverside Museum in New York the following year. The poet Frank O’Hara described Ethel’s work as “brilliantly colored post-Gorky abstractions (with concealed images)” in Artnews.”6 Among the ten women, Anna Walinska, Doris Caesar, and Ethel Katz were NAWA members. Ethel and Anna Walinska became close friends.

Ethel Schwabacher, Prometheus (1959).Oil on linen, 85 × 102 inches,© Estate of Ethel Schwabacher. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York. I

In 1955 Schwabacher showed work at the prestigious Stable Gallery annual exhibition and exhibited in two more shows at Betty Parsons Gallery, the second, in 1957, a solo show. Her 1957 catalog statement emphasized translating sensation, emotion, and vision into “solid and enduring form” through “conscious control of knowledge.”7 Her series *Et in Arcadia Ego*(Also in Paradise I am), referenced Guercini and Poussin, and works she identified as “rock gardens” and “seascapes” reflected her engagement with nature. A review in Artnews found she was “knowing in the current abstract idiom.” 8 That same year, the Whitney Museum published her groundbreaking biography of Arshile Gorky, featuring a preface by Lloyd Goodrich and an introduction by Meyer Schapiro, both celebrated art historians. It was one of the first comprehensive studies of a contemporary artist in book form.

*In 1958, Schwabacher participated in the Whitney Museum’s *Nature in Abstraction: The Relation of Abstract Painting and Sculpture to Nature in Twentieth-Century American Art. Her work shifted to epic mythology, beginning with Oedipus, Orestes, and Prometheus, expressing powerful messages of torture, deprivation, and redemption in action paintings.9 Her Oedipus at Colonus series, inspired by Sophocles, earned inclusion in the Whitney’s American Art of Our Century in 1961, where catalog authors Goodrich and Baur grouped her with prominent Abstract Expressionists like Rothko and Motherwell. She continued exploring mythological themes until the end of her life, as evidenced by a 1978 journal entry comparing herself to an unchained Prometheus.

Ethel’s fourth Parsons show in 1960 featured mythological works, with art historian Dore Ashton noting their “exuberant” colors and landscape-like movements.10 Her final Parsons exhibition in 1962 showed her transition toward more abstract color and form.

After Wolf’s death, a committed civil rights activist, Ethel assumed his place on the Greater New York Urban League’s board of directors and sat on the Board of Education Committee on Integration. Her powerful Birmingham Series* (1963-64), responding to racial violence, led to a split with Parsons, who refused to show the political works. She subsequently exhibited a series of expressionistic portraits, including ones of James Baldwin and Gorky, a the Green-Ross Gallery. Ethel returned to biblical and mythological themes of Orpheus and Eurydice, Sisyphus, Prometheus, Antigone, and Apollo by the late 1960s, 11a change coinciding with a switch to acrylic paints.

Ethel had significant shows at SUNY Buffalo’s Gallery 219 in 1972 and New York’s Bodley Gallery with Jeanne Reynal in 1976. The Buffalo News noted that at 69, she remained focused on universal themes of “life and death, love and hate,” with Ethel stating her preference for art that enhanced her understanding of humanity and nature.12

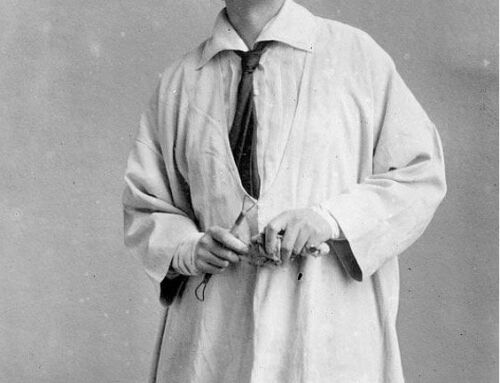

Anna Walinska, 1990, Ethel Schwabacher. Courtesy of Rosina Rubin.

Her 1973 article in Leonardo magazine, “Formal Definitions and Myths in My Paintings,” explored her diverse influences from Dante to Kierkegaard to Blake, explaining how she used diagonal lines to express tensions between “stability and instability” and “life and death.”13 In her late journals (1967-1980), she reflected deeply on her childhood experiences of abandonment, her early need for attention from those close to her, and her lifelong need for love. Though arthritis prevented her from painting after 1976, she continued artistic expression by drawing with markers and maintaining extensive journals. Ethel attempted suicide in October 1979,.and in November, she received the news that her psychoanalyst, Dr. Kris, had died.

Ethel began seeing a new therapist, Dr. Pfeffer, starting in 1981. Her daughter Brenda S. Webster and Judith E. Johnson, co-editors of Hungry for Light excerpts from Ethel’s journal, note that although Dr. Pfeffer saw Ethel’s arthritic pain as caused or intensified by psychological events, he does not view it as part of an early pattern of demands for parental attention. His therapy does not require the reconstruction or recovery of repressed memories of neglect or abandonment as Dr. Kris had, evidenced in Ethel’s journal writing. Dr. Pfeffer links the pain in her hands and fear of being alone at night to recovered memories of admonished episodes of autoeroticism as a child. Housebound, bedridden, unable to move, paint, or write, and never seeing her paintings collected in a major retrospective, Ethel accidentally choked to death in November 1984.

Three years later, in 1987, the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University organized a traveling retrospective in 1987, curated by art historians Greta Berman and Mona Hadler, later showing at Mills College and SUNY Albany. Anna Walinska, feeling the loss of a close friend, drew Ethel’s portrait in 1990.

In 2016–17, Ethel was among the twelve artists in the landmark traveling exhibition Women of Abstract Expressionism, organized by the Denver Art Museum and the Palm Springs Art Museum. In 2023, her work was included in the Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970 in the Whitechapel Gallery in London.[ That year, Berry Campbell Gallery in New York presented Ethel Schwabacher: Woman in Nature (Paintings From the 1950s), her first solo show in New York in 30 years.

Most recently, In early 2024, and later catching my attention, Berry Campbell Gallery presented Perseverance, the curated group exhibition of cross-generational women artists. Featuring 29 women artists’ paintings and works on paper, Ethel was one of the three NAWA members included in the show, the others being Dorothy Dehner and Mary Dill Henry.

Ethel’s works belong to numerous museum collections: the Brooklyn Museum, New York; the Denver Art Museum, Colorado; the Jewish Museum, New York; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minnesota; the Mint Museum, North Carolina; the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania; the Rockefeller University in New York City; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and the Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut.

Sources:

The primary source was Lisa N. Peter’s biography of Ethel Schwabacher, found at: https://berrycampbell.com/artists/73-ethel-schwabacher/biography/

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/ethel-schwabacher-papers-7336/series-1

https://www.artforum.com/events/ethel-schwabacher-220027/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ethel-Schwabacher

Mona Hadler, Ethel Schwabacher and the Paradise of the Real, in Greta Berman and Mona Hadler Ethel Schwabacher: A Retrospective Exhibition, exh. Cat. (New Jersey: Rutgers University, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum 1987).

Hungry For Light: The Journal of Ethel Schwabacher, edited by Brenda S. Webster and Judith Emylyn Johnson (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993.

1Ethel Schwabacher, “Foreword,” Pastels and Oils by Ethel Schwabacher, exh. cat.(New York: Passedoit Gallery, 1947).

2”Ethel Kremer Schwabacher, Artnews 44 (February 1, 1947), p. 50.

3 Whitney to Offer Arshile Gorky Art,” New York Times, January 4, 1951, p. 27.

4 Lloyd Goodrich, Schwabacher: Paintings and Glass Collages, 1951–1953, exh. cat. (New York: Betty Parsons Gallery, 1953).

5 Howard Devree, “Diverse Moderns: Stress on Expressionist and Abstract Approaches in the New Shows,” New York Times, June 7, 1953, p. X8.

6 Frank O’Hara, “Ten Women Artists,” Artnews 52 (June 1, 1954), p. 56.

7 Ethel Schwabacher, Ethel Schwabacher: Paintings, 1956–57, exh. cat. (New York: Betty Parsons Gallery, 1957).

8“Ethel Schwabacher,” Artnews 56 (December 1, 1957), p. 11

9,11 https://berrycampbell.com/artists/73-ethel-schwabacher/biography/

10 Dore Ashton, “Art: Double Anniversary Celebrated at Exhibition,” New York Times, February 5, 1960, p. 24.

12 Jean Reeves, “A Successful Artist Works On, Still Seeking the Best Painting of All,” Buffalo News, June 7, 1972, p. 91.

13 Ethel Schwabacher, “Formal Definitions and Myths in My Paintings,” Leonardo 6 (Autumn 1973), p. 55.

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A , Ed.D. Website

Historian, Co-Chair NAWA Historical Research. NAWA Luminaries

Email: NAWA Historian

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889