NAWA Luminaries – Anna Walinska

NAWA Luminaries is the intersection of NAWA’s Historical Research and current exhibitions around the United States highlighting celebrated NAWA members.

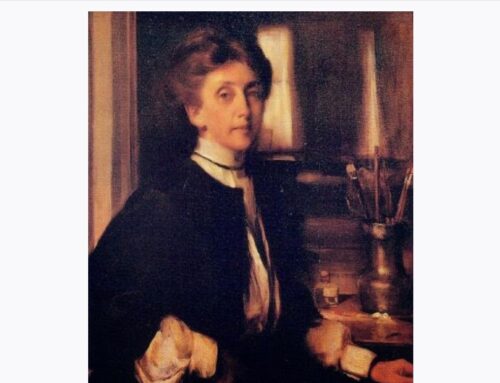

Anna Walinska photo, 1926 (photo courtesy Atelier Anna Walinska)

Anna Walinska : West Meets East, an Artist’s Journey Around the World, 1954-55, opens on June 4th at Graham Shay 1857 and runs through July 11th.

An American painter and celebrated NAWA member, Anna Walinska was a prolific artist, creating more than 2,000 works on canvas and paper throughout her lifetime. She is known for her colorful Modernist works, collages done with handmade Burmese Shan paper, and a large body of works in response to the Holocaust.

Born in London in 1906, Anna Walinska was the daughter of Jewish labor leader and self-made Russian immigrant Ossip Walinsky and sculptor-poet activist Rosa Newman. In 1914, the family moved to Brooklyn, New York. Anna studied dance as a young girl, and at the age of 12, she enrolled first at the National Academy of Design and then at the Art Students League, her studies indicating a precocious emerging talent in the visual arts. Her oldest known work is a watercolor dated 1918 when Anna was 12.

Anna dreamed of studying art in Paris, but her father refused to financially support the venture, wanting his daughter to attend college. Undeterred and resourceful, Anna approached the owner of the leather goods company where her father worked. Telling her father’s boss she needed $2,000 to cover expenses for a year abroad, she proposed an arrangement: if he provided the funds, she would paint him a copy of a masterpiece. He wrote a check on the spot.

Anna sailed off to live in Paris at the age of 19, finding residence on the Left Bank – first at a pension on Rue Stanislas and then at 67 Rue Madame, around the corner from Gertrude Stein. She studied with André L’Hote and at the Grande Chaumière. Anna spent countless hours perched on a ladder at the Musée Luxembourg, copying Paul Baudry’s La Fortune et le Jeune Enfant for her benefactor. Months later, when she returned to New York with the painting in hand, her father took one look at it and was immediately struck by its quality. Without hesitation, he reimbursed his boss the full amount and decided to keep the remarkable piece for himself.

Convinced Paris was where she needed to be, Anna boarded the Ile de France and returned to Paris for the remainder of the decade. Paris was then a great gathering place for avant-garde artists working in all manner of expressions from all over the Western World. Anna became friends with composers Poulenc and Schoenberg. The experience was auspicious, and her work was exhibited at Salon des Indépendants, where artists not selected for the Beaux-Arts Exhibitions staged their own shows for modern art. Many of them became quite famous, including Picasso, who, along with Matisse, had a significant influence on her work. Indeed, Anna made a drawing of Picasso in a café, placing it in a sealed box for the safe return home, where it remained for over seventy years.

Anna Walinska, Paris Nude #58, 1929, Ink on paper (photo courtesy Atelier Anna Walinska)

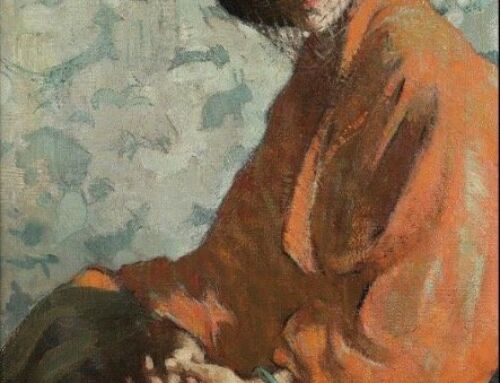

In Paris, Anna finally had the opportunity to attend nude figure drawing classes with live models—something she had long yearned to experience. As her confidence grew, she began creating nude self-portraits and eventually posed as a model for fellow artists. Anna produced hundreds of line drawings, delicately capturing her subjects’ forms in visceral, spontaneous sketches that manifest her grasp of composition. During her stay in Paris, she developed what she would refer to as a calligraphy of line that would remain with her from that time on.

Drawing and painting weren’t her only interests in Paris. Anna screen-tested for the Gaumont film Joan of Arc and met Maurice Chevalier and Josephine Baker on set. Interestingly, Anna formed her closest friendships with musicians, including Arnold Schoenberg, Francis Poulenc, Jascha Heifetz, composer Edgard Varèse, pianist Josefa Rosanska, and her husband, Rudolf Kolisch. Anna also found her first romance with Schoenberg’s student, Max Deutsch, with whom she frequently walked to Longchamps, developing an enduring love for horses.

Anna Walinska, “Self Portrait, Paris” (1927), oil on canvas (photo courtesy Atelier Anna Walinska)

When Anna returned to New York in the early 1930s, she secured work as a curator with the Federal Art Project (FAP). At a time when few jobs were available in America, the FAP not only enabled artists to continue their craft but also to earn a living and exhibit their work. Eager to bring the avant-garde sensibility she had absorbed in Paris back to New York, she co-founded the Guild Art Gallery at 37 West 57th Street with Margaret Lefranc, a wealthy acquaintance whose Russian Jewish family, like her own, had settled in New York City.

Anna and Margaret’s lofty mission was to showcase artists of genuine merit, whether known or unknown, entirely independent of commercial considerations.1

She had become fluent in French during her years in Paris, a skill which enabled her to seek out Fernand Leger at a nearby hotel and convince him to view Gorky’s work.

Arshile Gorky with Anna Walinska (left), Emily Walinsky (center), and Rosa Newman Walinska (right) (1933).Anna Walinska papers, circa 1927-2002, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

A solo exhibition of Arschile Gorky’s work in 1935 (his first in New York) was among the Gallery’s first shows. Anna first met Gorky in the late 1920s when they were part of a circle of artists. At that time, she’d already been exposed to avant-garde art on two continents and had been painting for over a decade. She often claimed that her friendship with Gorky was one of the reasons she started the Gallery. Other shows featured artists such as Chaim Gross, Raphael Soyer, and Theodore Roszak.

Anna Walinska, “Woman in Interior” (1936), collage with ink drawing on paper, 22 x 19 inches (photo courtesy Atelier Anna Walinska)

Although she was not a strong promoter of her own work, she took particular pride in the fact that when Art News reviewed a group show in 1936, it was Anna’s Portrait of Emily (1932) that they chose to illustrate the piece. The reviewer noted: “She studies form and tonal relation with the greatest of care, and it is interesting to follow her work as it matures.”

Anna Walinska, Portrait of Emily, 1932, oil on canvas, (photo courtesy Atelier Anna Walinska)

The Guild Art Gallery’s lack of commercial success, combined with the fact that it was still in the midst of the Great Depression, ultimately led to the venture’s demise. The Gallery closed by 1937 — the year Gorky painted Anna’s portrait, and her own work was featured at the 1st Annual Members Exhibition for the American Artists’ Congress.

Anna Walinska, The Picnic, 1947, copyright/Atelier Anna Walinska, courtesy. Atelier Anna Walinska

Anna persevered, appearing in the Yiddish Theatre, performing with a Flamenco dance troupe, and serving as Assistant Creative Director of the Contemporary Art Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair. Group shows in these early years included Artists for Victory; Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1942; Paintings of the Year, 1946; National Academy of Design; Recent Drawings USA, Museum of Modern Art, 1956; Baltimore Museum of Art, 1957; and numerous exhibitions organized by the American Federation of Modern Painters & Sculptors and the National Association of Women Artists. Anna’s mother, Rose Newman, an artist in her own right, had become a member of NAWA in 1938, and Anna joined in 1952, winning a National Association Medal of Honor for her watercolor, Cain and Abel, in 1957. Anna was featured in a show of ten women artists sponsored by the National Council of Women of the United States at the Riverside Museum in New York in 1954. Among the ten women, Anna, Doris Caesar, Ethel Katz, and Ethel Schwabacher were all NAWA members. Louise Nevelson, who joined NAWA the same day in 1952 as Anna, would become a lifelong friend.

From November 1954 to May 1955, Anna, traveling alone, took a trip around the world on five different airlines to Honolulu, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Burma, New Delhi, Karachi, Cyprus, Israel, Istanbul, Athens, Rome, Perugia, Florence, Venice, Pompei, Naples, Sorrento, Capri, Nice, Barcelona, Madrid, Toledo, Lisbon, and finally to Bermuda. Anna wrote of her custom for each flight: “I sang a song of prayer when I got on a plane and sang a song of praise to the infinite when I landed: I am here to continue my journey.”2

The journey included a four-month sojourn in Burma, where her brother, Louis Walinsky, was serving as an economic advisor to Prime Minister U Nu. At the time of her departure for Burma, Anna may have been on the verge of being “discovered” – she had just received a letter from James Johnson Sweeney, the director of the Guggenheim Museum, saying that he was impressed with her work and wanted to visit her studio. Although she later called this “the greatest moral encouragement I have ever had,” she was driven by the desire to explore and express herself through art. There is no doubt that she would never have traded her voyage for commercial success. “3

In Burma, the warmth of its people and the country’s landscape, featuring incredible sunsets, magical pagodas, and colorful marketplaces, inspired Anna’s art. Keepng a diary of the trip, now in the collection of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, she wrote: “It was the end of so much that was precious and very beautiful, and I was very fortunate that I came at a time where even though the West had encroached with the clothes and certain values, still there was a mixture of the two, a juxtaposition which was fascinating.”4

Anna Walinska painting Burmese Prime Minister U Nu, Rangoon, 1955 – Anna Walinska papers, Smithsonian Archives of American Art

Among the many portraits she made during her stay in Burma, one of Prime Minister U Nu. U Nu would become part of the collection at the Asia Society in New York City. She worked on U Nu’s portrait in a formal dress and high heels, and would note: “To have had the unique experience of painting a world leader, who besides being a man of action has the rare qualities of a truly good soul, the gentleness and smiling peace of his good nature, his kindness which is evident, and coming to know him has been for me a great privilege.” Presenting the finished canvas to U Nu was one of the most memorable days of my stay.” She wrote of saying to him, “Mr. Prime Minister, I have sought in my interpretation of your character to convey the qualities of a man of action plus those of a man given to deep reflection and meditation. That is why I sought an informal, relaxed and characteristic pose and mood, rather than the more formalistic approach. I want to say to you how deeply grateful I am that my path in life has led me to your country which I have come to love as well as your people. I carry with me unforgettable memories which will always remain in my heart.”5

Other persons with whom Walinska spent time in Burma included journalists Joseph Alsop and Max Lerner; Israeli Ambassador to Burma David Hacohen and his wife, author Bracha Habas; Lady Patricia Gore Booth, wife of the British Ambassador to Burma and a life-long supporter of the cause of a free democratic Burma; Mrs. Oswald Lord, U.S. delegate to the UN; and the Burmese political leaders and artists – U Thant, secretary to the Prime Minister (later Secretary General of the UN); U Hla Maung, Burmese Ambassador to China; Bo Letya (Commander of the Burmese Defense Army under Bogyoke Aung San) and Bo Setkya (both founding members of the Thirty Comrades, fighters for their country’s independence from the British); and painters Ngwe Gaing, Hla Shein and M. Tin Aye.6

While in Burma, artists took Anna out to paint en plein air, and she shared with them her knowledge of the contemporary art world and instructed local artisans on the art of building an easel and stretching canvas. The Burmese. Hla Shein wrote of her influence: “The vast majority of artists in Burma follow the realistic approach. They have now for the first time seen and heard a modernist, who appears entirely different from the only brand they had known. They have also had an opportunity to see her recent work and were agreeably surprised to realize that abstraction can excite emotions in the same way as realism. “7

Anna also made personal artistic discoveries, falling in love with the Shan paper, handmade in the northeast province of Burma. She used it for a series of collages exhibited in 1961 at the Monede Gallery on Madison Avenue in New York. The aerial geological photos of the country she acquired inspired abstract paintings.

Anna Walinska, Seaform (1961), oil and Burmese Shan paper on board, (photo courtesy Atelier Anna Walinska)

Upon her return home to New York in 1955, Anna became a teaching artist in residence at the Riverside Museum, where she exhibited with sculptor Louise Nevelson, among others.

Anna Walinska, Nevelson, 1975, Oil on board, courtesy Graham Shay 1857 Gallery.

Anna turned her attention to creating a substantial body of work in response to the Holocaust. It was long before museums and memorials existed to house and display such pieces for public viewing. She included a selection of the works in her one-woman retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1957.

Anna Walinska, Holocaust Series: Paintings and Drawings Exhibition Installations, 1979, AAA Anna Walinska papers, 1927-2002, bulk 1935-1980. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Anna Walinska, 1960 in NYC studio. Copyright/Atelier Anna Walinska, Image courtesy Graham Shay Gallery.

Following a solo show at the Monede Gallery in 1961 of Shan paper collages she had started making after spending months in Burma, there was a lull in her exhibitions. Her Holocaust series was subsequently exhibited as a group of 122 works at the Museum of Religious Art at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York in a 1979 retrospective. Anna’s niece, Rosina Rubin, would note that it was a time when the art world was morphing into the art business, and Anna had little interest in fitting in.8

In an interview with Dr. Judith Shapiro on radio station WEVD in November 1979, Anna answered the question of how she happened to dedicate herself to the Holocaust in her work with: “I must speak of my parents, generations of my immediate family [who] were and are engaged in Jewish public service. How could I help but be profoundly involved and influenced by their activities? “

Anna’s Holocaust work was first exhibited in Eastern Europe in 2000 at the Ghetto Museum at the Theresienstadt Memorial in the Czech Republic. Works from this group are in the permanent collections of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,Yad Vashem in Israel, the Clark University Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, and the Judah L. Magnes Museum. After Anna’s death in 1997, solo exhibitions stalled, except for a notable show in 2019 at the former Riverside Museum (now the Master Gallery, located in the lobby of the Art Deco skyscraper), where Anna had maintained a studio for many years.

In 2003, NAWA established the Anna Walinska Memorial Fund with a substantial donation from Anna’s brother, Louis Walinska. The intention was to award an annual achievement prize or sponsor an artist, creating a significant impact on recipients’ professional careers. In an interview about her aunt, Rosina Rubin, who sits on the NAWA Board of Directors, noted: “If you are a passionate artist or whatever, it’s not an option to not do it. You just have to keep doing it, and hopefully, you find a way. You find a support network and people to share the experiences.”9

In 2015, Lawrence Fine Art in East Hampton, New York, offered a selection of works from the 1950s and 60s. Notably, in January 2023, the Graham Shay 1857 gallery presented Calligraphy of Line: The Drawings of Anna Walinska, focusing on Anna’s figure drawings from the late 1920s and later abstract works on paper inspired by Burma from the 1950s. The current exhibition, Anna Walinska: West Meets East, an Artist’s Journey Around the World, 1954-55, brings forth the work inspired by Anna’s stay in Burma seventy years ago. Here are some of the highlights:

Anna Walinska, Landscape-Pagoda, 1955 (c.), oil applied with a palette knife on paper, 5 x 4, courtesy of Graham Shay, 1857.

Anna Walinska, Figures in Landscape-The Lake, oil applied with palette knife on paper, 8.7 x 9, courtesy of Graham Shay 1857,

Annna Walinska, Miss Ichikoo, 1955, watercolor and collage on paper, 26 x 21, courtesy of Graham Shay 1857

Sources:

5https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/anna-walinska-papers-6942/series-4/box-1-folder-74

4https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/anna-walinska-papers-6942/series-4/box-1-folder-73

https://archive.org/details/whowaswhoinameri0003unse/page/3440/mode/2up

3https://grahamshay.com/artist/anna-walinska

https://hyperallergic.com/569666/anna-walinska-arshile-gorky-missing-portrait/

Lisle, Laurie (1990). Louise Nevelson: A Passionate Life. Simon & Schuster.

9https://libmagazine.com/featured-artist-anna-walinska-a-woman-to-revere/

1https://www.margaretlefranc.org/anna-walinska-bio

8https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/05/12/anna-walinska-american-art-fair-graham-shay-1857

Van Riper, Kate, Archivist for Women Artists’ Collections, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, NAWA Archives

2,6,7https://www.walinska.art/about/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Walinska

——-

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A , Ed.D. Website

Historian, NAWA Historical Research, NAWA Luminaries

Email: NAWA Historian

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889