NAWA Luminaries – Amelia Peabody

NAWA Luminaries is the intersection of the National Association of Women Artists’ historical research and current exhibitions around the United States highlighting celebrated NAWA members.

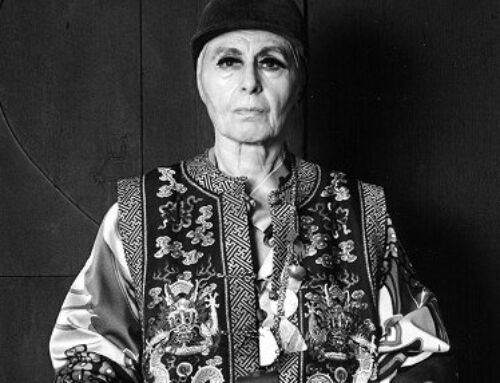

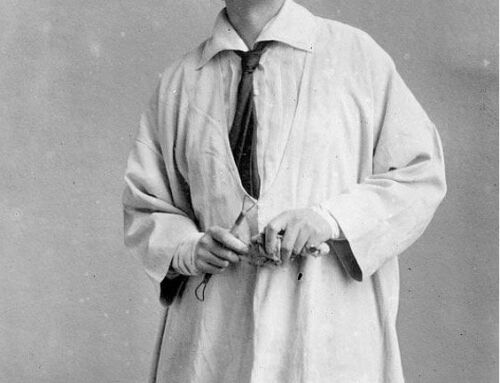

Amelia Peabody, from her 1922 passport application.

NAWA Luminary Amelia Peabody

by Susan M. Rostan, MFA. EdD. NAWA Historian

A NAWA artist and honorary VP, Amelia was also a philanthropist who arguably transformed education, medicine, arts, science, and conservation throughout Massachusetts. Through an impressive foundation, her impact continues to shape life in the Commonwealth. From April 19 through June 29, the Dover Historical Society presents Amelia Peabody as an artist, philanthropist, and visionary. It is the first exhibit of Amelia Peabody’s work since 1975, featuring more than 40 sculptures on loan from private and public collections.

Amelia’s remarkable life and achievements were brought to our attention by Judy Schulz, who researched Amelia for this exhibition. I met Judy in October 2024 when we talked about Amelia during a Zoom interview. The interview portions have been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

SMR: I’m intrigued by your involvement in this research. How did you get involved in this project?

JS: I’m a history major who worked at Childs Gallery for 20 years. We were in Boston and New York, and the man who founded the gallery, Charlie Childs, created it during the Depression with an eye on looking at artists who were undervalued and accessible. Guess who was undervalued and accessible: Women artists. So, it has a very rich tradition of focusing on women artists, something dear to my heart.

Amelia Peabody, Hurricane and Flood, courtesy of Judy Schulz

I just stumbled on Amelia Peabody. I grew up in the town where she had her studio, and I certainly knew of her, although I didn’t have a personal relationship with her when I was a young kid. I’m a trustee at the Dover Library, and we have seven sculptures of hers. Looking at those beautiful sculptures, I realized there wasn’t even proper signage. It just said the gift of Amelia Peabody. And one says Hurricane. Well, it’s not Hurricane; it’s Hurricane and Flood, and it’s commemorating the enormous hurricane that came through New England in 1938 and destroyed something like 55,000 homes, if you can imagine. It’s considered the most tragic storm that has ever hit New England. This sculpture commemorates that, and she showed it at the Whitney Museum with the National Sculpture Society in 1940. So it’s got a story.

SMR: Amelia has quite a story, too.

Amelia Peabody: A Life of Artistic Passion and Purpose

Amelia Peabody was born to an illustrious family in Marblehead, Massachusetts in 1890. Her mother, Gertrude Bayley Peabody, descended from Captain Robert Gray, the acclaimed American navigator who was celebrated for pioneering circumnavigation and establishing Chinese trade relations. Her father, Frank Everett Peabody, was a partner in the prestigious investment firm Kidder, Peabody & Company, and the family divided their time between an elegant Back Bay townhouse designed by the notable architects William R. Emerson and Carl Fenner and a seasonal residence in Marblehead.

A photograph from about 1898 shows Amelia among a group of sixteen children, with only three boys, given as members of Miss Fish’s School. At some point, or on occasion, Amelia also had a French governess. In the years preceding her brother’s death, in 1900, Amelia attended the Winsor School for Girls, located near home. The school offered drawing, art history, French, Latin, diction, and math courses. Amelia left Winsor without a formal diploma. Her parents did not expect Amelia’s future to include a college education.1

Despite societal expectations that she become “a lady of society,” Amelia harbored a profound passion for art. Although she did not pursue collegiate education, she dedicated herself to artistic study in Boston, New York, and Paris. Following her formal societal debut in 1909, Amelia studied under Bela Pratt at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Although an appropriate activity for a young debutante, art was considered a finishing touch. Amelia saw it differently, taking a stand against her mother, who feared Amelia’s sculptural pursuits might diminish her prospects in the marriage market.

Judy Schulz noted: “Studying at the museum school is a tremendous struggle because she’s a society girl. And the idea of having nude male models and things like that was scandalous. She was very prideful of not embarrassing her parents. At the same time, she loved art, but she could only do it from nine to one. In the afternoon, she had riding, piano, or other lessons appropriate for a young woman of that day. The family would go to Europe for a three- or four-month trip, which would also interfere with her studies. But in 1914, she suffered a breakdown. She was cognizant that she had anxiety and depression. She writes about it in her diaries at the Mass Historical Society.

And she ends up at a sanatorium in Marblehead, Massachusetts, where the man running it, Dr. Herbert Hall, is a pioneer in occupational therapy. He is taking the ideas of the arts and crafts movement of making things by hand and combining them with ideas of medicine.

Some of the patients at the sanatorium are very, very ill. And some, like Amelia, are there to get their wind back under their feet and get better, but with the hope of leaving. Dr. Hall puts her in charge of modeling, doing clay piles, or doing urns for garden statuary, which was very popular then. He tells Amelia that this art is going to be your path. And she understands that because she saw it herself. When her brother died of diphtheria, when she was about 10, she had found art a place that was very soothing and very therapeutic for her.”

Amelia’s life philosophy was marked by wholehearted commitment. In a revealing 1912 diary entry, she wrote, “If I ever do take up a charity, I intend to do it, and not half do it.”2 This same intensity characterized her approach to art, which was deeply influenced by personal experience. Much of her work exploring musical themes drew inspiration from memories of her elder brother, Everett Peabody, who died at age 15.

Tragedy struck again when her father, Frank, died in 1918 following a brief illness. Two years later, her mother, Gertrude, remarried to William Eaton, a longtime family friend. As the sole surviving heir to Frank Everett Peabody’s estate, Amelia chose independence over marriage, preferring instead the company of her family and the pursuit of her artistic passions.3

Back on her feet, she had returned to Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts and studied with Charles Grafly for a year, beginning in 1917. Amelia’s sculptural work focused primarily on animals, figures, and portraits, executed in stone, bronze, and ceramics. She furthered her artistic education at the Archipenko School of Art. Northeastern University, awarded her an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree in recognition of her contributions to the field. Her talent earned her exhibition opportunities at prestigious institutions, including the Pennsylvania Academy (1922-1924), the Art Institute of Chicago (1932), and the Boston Sculpture Society.

Amelia had her first one-woman show in 1930, followed by two one-woman shows. The 20s and 30s were a robust time for her.4 In 1936, Amelia joined the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (NAWA), where she would later serve on the Jury of Awards in 1942 and 1944. Her prominence in the organization led to her appointment as an Honorary Vice President in 1943. Her enduring impact on the arts was commemorated with the Amelia Peabody Prize, first awarded in the 1948 Annual Exhibition and continued until 1984.

Amelia Peabody, Telegram, 1939, exhibited at the NY World’s Fair, MA Historical Society, courtesy of Judy Schulz

Her work received international recognition at the 1939-40 World’s Fair. Amelia exhibited at the Whitney Museum of Art and the Boston Athenaeum, with her final exhibition in 1975, when she was 85.

Country Life and Agricultural Pursuits

Beyond her artistic endeavors, Amelia was an accomplished horsewoman and agricultural enthusiast. In the early 1920s, she began acquiring farms and farmland in Dover, Massachusetts, where she dedicated herself to equestrian pursuits and animal husbandry. Her breeding programs produced exceptional thoroughbred horses, white-faced Hereford cattle, and Yorkshire pigs, all renowned for their superior bloodlines and breeding quality.

Judy Schulz added: “There was a problem of dwarfism with cattle in America, the Hereford lines; each generation was getting smaller. Amelia went to England, bought six female calves and the biggest prize bull you can imagine, and brought it back. She redefined the Hereford breeding lines in America. And there are pictures of her with these guys from Oklahoma and Texas, wearing the big 10-gallon hats and stuff. And again, she’s the only woman in the room. ”

Philanthropy and Innovation

Amelia’s commitment to service manifested in her long tenure as Chairman of the Arts and Skills Service of the American Red Cross. In this capacity, she pioneered art therapy programs for wounded service members during World War II. Amelia recruited fellow NAWA members Agnes Ann Abbott (1938), Jessica Anthony Sherman (1942), and Kay Peterson Parker, who joined NAWA in 1957.

Judy Schulz explains: “She takes that concept of art therapy to the four Boston area VA hospitals and trains hundreds of volunteers using her society ties and her connections in the art world to train these volunteers in leather work, painting, sculpture, sewing, and stenciling. There were articles written about it at that time. In the pictures of the soldiers, with their heads in horrible braces, they’re holding up some embroidery that they did. She understood the power of art and how it had helped her.”

Amelia Peabody, Boy and Horse, courtesy of Judy Schulz

This initiative later expanded to serve hospital patients with various needs in the post-war period. Her dedication to helping veterans reintegrate into civilian life led her to teach returning GIs occupational arts, such as ceramics, providing them with skills for gainful employment. True to her wholehearted approach to charity, she even welcomed students into her Commonwealth Avenue townhouse. She turned her garage into a studio and installed a kiln, firing all the different pieces that the soldiers made. The success of that endeavor traveled to Children’s Hospital in Boston, McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass General Hospital, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and all the hospitals started arts programs.5

In 1942, Amelia established the trust that would later become the Amelia Peabody Foundation upon her death, ensuring her philanthropic legacy would continue. Her forward-thinking nature was further demonstrated in 1948 when she financed the construction of the Dover Sun House on her property—one of the world’s first solar-heated residences and a testament to her innovative spirit, built to provide housing for the people who worked her farms.

Judy Schulz had a story about the horse sculpture with a boy on it. “…it’s just called Boy and Horse. And I thought, who is that boy? What is this about? The boy’s name was Dennis Wile, and his father, Henry Wile, was the contractor who built Amelia’s solar house. Young Dennis would tag along with his dad because there were goats, thoroughbred horses, and Hereford cattle, and he was out in nature, and there was always something fun going on. Amelia saw him one day and said, I need you to sit for this piece I’m working on. And so he did, and it’s this gorgeous piece at the library entrance. Fast forward probably 15 years later, when he’s 25 years old, in General Patton’s war room, and is the official photographer. He was photographing the generals and the soldiers, and now and then, he was photographing bridges and things for strategy. And he was there for the liberation of Buchenwald. His archives are at Emory University, and they are called Witness to the Holocaust. That little boy sitting on that horse. Each of her pieces has these vivid stories that I’m just beginning to find out.”

In 1981, Amelia founded the Amelia Peabody Pavilion, housing a large animal clinic at the Tufts-New England Veterinary Medical Center in Grafton, Massachusetts. This endeavor reflected her lifelong commitment to animal welfare and veterinary medicine.

Continuing the medical philanthropy of her father, step-father, and uncle, Amelia donated generously to numerous Boston-area institutions dedicated to alleviating human suffering. Her lifelong fascination with science led her to support groundbreaking research to prevent illness and discover new treatments. She served on the boards of several esteemed Boston medical institutions, including Boston Lying-in, Children’s Hospital, and Joslin Diabetes Clinic.

Judy Schulz notes: “There are wonderful photos of her at these corporate meetings for Northeastern University, the Museum of Science, or Mass General Hospital. And she’s the only woman in the room. And she would usually wear a hat. And then there would be a sea of black, dark suits and men sitting there, and this little woman with a hat. So I think she understood what that was like. So, she sought out women in similar situations with ceilings to crack. Her patronage extended to various engineering innovations, including the solar home built on her Dover property under the direction of scientist and Hungarian émigré Maria Telkes. Eleanor Raymond, an MIT architect, designed her studio and stables. They had things in front of them that they sometimes couldn’t control.”

Despite her influential position, Amelia remained hands-on in her charitable work. Even in her later years, she would don a volunteer uniform and work at the front desk of Massachusetts General Hospital. Her commitment to education and scientific exploration fostered a lasting relationship with the Museum of Science, where a wing still bears her name today.

Final Years and Lasting Legacy

As Amelia aged, her attachment to her farm deepened, and she often declared the “porch at Mill Farm” her favorite place. She expanded her land holdings and funded forest preservation efforts. When she could not ride in her later years, she enjoyed watching others gallop by and enjoy the land she had so lovingly preserved.

At the time of her death, Amelia was Dover’s largest landowner. She leveraged this commitment to agriculture by providing substantial funding to Tufts Veterinary School, New England’s only land-grant veterinary college. Upon passing, she also donated a memorial to the National Association of Women Artists (NAWA).

Amelia Peabody died at 93 on May 31, 1984, at her beloved Mill Farm in Dover, leaving a remarkable legacy of artistic achievement, scientific patronage, and compassionate philanthropy. Following her passing, the Amelia Peabody Memorial Award was created in 1986, initially presenting two awards annually with at least one dedicated to sculpture, before evolving in 1993 to a single annual award for sculpture until 2015, when it expanded to include photography, printmaking, and digital art.

Two foundations bear her name: The Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund and the Amelia Peabody Foundation. The Amelia Peabody Foundation continues to support and innovate services for disadvantaged youth across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund gives grants to qualified non-profit organizations in Massachusetts in medicine (human and animal), social welfare, visual arts, historic preservation, and land conservation.

Sources:

2,3: https://ameliapeabody.org/about-amelia-peabody/

https://www.askart.com/artist/Amelia_Amy_Peabody/117361/Amelia_Amy_Peabody.aspx

https://collections.libraries.rutgers.edu/national-association-of-women-artists

4, 5 Judy Schulz interview, October 2024.

Kate Van Riper, Archivist for Women Artists’ Collections, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries

1http://Linda Smith Rhoads, Amelia Peabody, for The Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund.

Peter Falk, Who Was Who in American Art @ https://archive.org › details › whowaswhoinameri0000falk

https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fap018

https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fa0046

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amelia_Peabody_(philanthropist)

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A, Ed.D. Website

Historian, Chair NAWA Historical Research, NAWA Luminaries

Email: nawa_historian@thenawa.org

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889

1Ethel Schwabacher, “Foreword,” Pastels and Oils by Ethel Schwabacher, exh. cat.(New York: Passedoit Gallery, 1947).

2”Ethel Kremer Schwabacher, Artnews 44 (February 1, 1947), p. 50.

3 Whitney to Offer Arshile Gorky Art,” New York Times, January 4, 1951, p. 27.

4 Lloyd Goodrich, Schwabacher: Paintings and Glass Collages, 1951–1953, exh. cat. (New York: Betty Parsons Gallery, 1953).

5 Howard Devree, “Diverse Moderns: Stress on Expressionist and Abstract Approaches in the New Shows,” New York Times, June 7, 1953, p. X8.

6 Frank O’Hara, “Ten Women Artists,” Artnews 52 (June 1, 1954), p. 56.

7 Ethel Schwabacher, Ethel Schwabacher: Paintings, 1956–57, exh. cat. (New York: Betty Parsons Gallery, 1957).

8“Ethel Schwabacher,” Artnews 56 (December 1, 1957), p. 11

9,11 https://berrycampbell.com/artists/73-ethel-schwabacher/biography/

10 Dore Ashton, “Art: Double Anniversary Celebrated at Exhibition,” New York Times, February 5, 1960, p. 24.

12 Jean Reeves, “A Successful Artist Works On, Still Seeking the Best Painting of All,” Buffalo News, June 7, 1972, p. 91.

13 Ethel Schwabacher, “Formal Definitions and Myths in My Paintings,” Leonardo 6 (Autumn 1973), p. 55.

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A , Ed.D. Website

Historian, Co-Chair NAWA Historical Research. NAWA Luminaries

Email: NAWA Historian

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889