NAWA Luminaries – Dorothy Dehner

Nawa Luminaries is the intersection of NAWA’s Historical Research and current exhibitions around the United States highlighting celebrated NAWA members. The last blog announced the exhibition at the Southampton Arts Council, Heroines of the Abstract Expressionist Era: From The New York School to The Hamptons at the Southampton Arts Center in Southampton, New York, which closes on December 17th. The works of the 35 artists in the show are part of the collection of Rick Friedman and Cindy Lou Wakefield and include paintings by Audrey Flack and four more NAWA members, Nell Blaine, Dorothy Dehner, Buffie Johnson, and Louise Nevelson. We have already shared a link with Audrey Flack’s autobiographical story of the Abstract Expressionist movement she was a part of and her evolution as a painter and sculptor. The other four NAWA members are the focus of our continuing historical research.

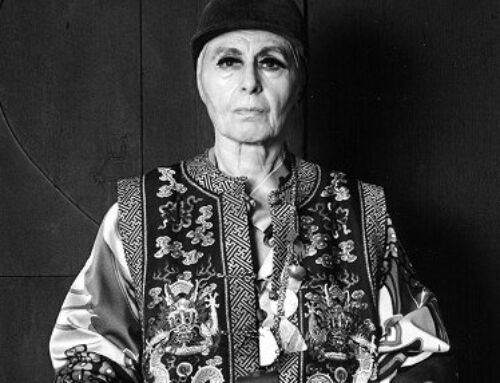

Photo by Arthur Tress, courtesy of the photographer. National Museum of Women in the Arts

Born in 1901 in Cleveland, Ohio, Dehner studied painting with three of her aunts, amateur artists, and then acting at UCLA in 1922. She moved to New York in 1923, studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, and worked in off-Broadway productions. In 1925, she traveled alone in Italy, Switzerland and France.

While touring Europe in 1925, Dorothy Dehner was enthralled by the Cubist sculpture she saw there, and upon return to the United States, she enrolled in the Art Students League and studied with Kimon Nicolaides, Kenneth Hayes Miller, and Jan Matulka. Under Matulka’s guidance, she developed a modernist style. Dehner married David Smith in 1927 and became part of a circle that included the artists John Graham, Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky, and Milton Avery.

In 1940, Dehner and Smith bought a house in Bolton Landing, New York, and her work turned away from modernism to painting realist scenes in a naïve style chronicling their life in the country.

Dorothy Dehner, “Fortissimo”, 1993, fabricated aluminum painted black, 19′ 4″ x 4′ 6″ x 4′ 6″, Museum Purchase with funds provided by the Judith Rothschild Foundation, and Gift of Dorothy Dehner Foundation

In 1945, Dehner moved back to New York City, and disturbing images filled her work, a series she titled “Damnation,” reflecting her personal life in the waning years of her marriage and the horrors of World War II. She left Smith in 1950 and, with a new beginning, obtained a degree from Skidmore College, had her first solo show in New York in 1952, and remarried in 1955 to Ferdinand Mann, the widowed father of one of her students.

Her new work focused on sculpture using the lost wax process. She also studied printmaking in Hayter’s Atelier 17, where she met Louise Nevelson and resumed an abstract style in her prints, primarily engravings. A solo exhibition of her drawings at The Art Institute of Chicago in 1955 was followed in 1959 by participation in the “Recent Sculptures U.S.A.” exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art and a retrospective of her sculpture at The Jewish Museum in New York in 1965. In the 1970s, she developed a unique lithographic technique at the Tamarind Institute in New Mexico, and in the late 70s, Dehner began sculpting in wood and worked on a large scale using Corten steel and on small-scale works with bronze.

Dehner joined the National Association of Women Artists in 1960 and was named an Honorary Vice President of NAWA in 1984. Interviewed by NAWA in 1984, she noted how her marriage to David Smith held her back artistically: “I thought I was good, too, but I didn’t necessarily think anybody else would think I was good.” She added:

“I think it had to do with many things…a childhood in which I had lost my father, mother, sister, and brother before I was fifteen. You’re an awfully different kind of kid if you have that happen to you. I was very pleased that I got strong enough to feel more confident about my luck and in relation to other people, but it took a long time. I think every artist needs support from fellow artists, and the organizations dominated by male artists were not as welcoming to the females.”

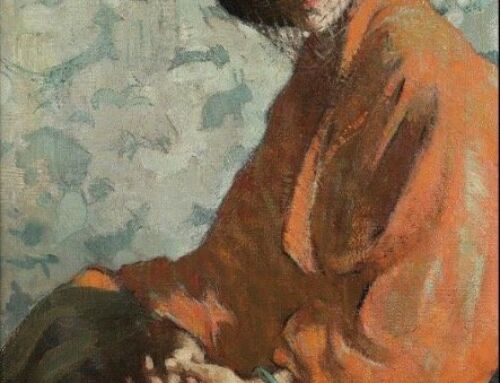

Landscape. 1967. Bronze.. 49 1/8 x 10 3/4 x 23 1/2 inches. signed. Collection of Rick Friedman and Cindy Lou Wakefield

Dehner, deeply touched by her recognition by NAWA, told the organization she was moved to be asked and accepted the honor with love and appreciation. “It’s wonderful to have recognition and give other people pleasure, interest, or even a hard time. To have a response, it’s what’s important. The biggest response you get is the kick in your own studio.”

In 1994, the year before she died, she was the subject of a retrospective at the Katonah Museum of Art in 1993, which later traveled to the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Susan M. Rostan, M.F.A , Ed.D. Co-Leader: NAWA Historical Research Team. Website.

Signature Member of the National Association of Women Artists

NAWA. Empowering Women Artists Since 1889