By Linh Vivace

Back in June, I pitched an idea to Sandra for the NAWA NOW Magazine: how about highlighting the way national change can occur at the level of local community? While federal laws and initiatives can remove legal challenges and help to jumpstart conversations, women will have had their personal and professional paths imperceptibly (and not so imperceptibly) shaped by local influences long before statutes take over. Women first grow up in towns and cities across the country, making decisions deeply affecting their adult lives all the while – or they may instead arrive at a later stage in life from abroad, with their first set of challenges being local acceptance and day-to-day life. The circumstances are as diverse as the women themselves, but we all face stakes that are simply a product of location and community. That is why I wanted to undertake this project. It serves as a reminder that how we are treated and supported at all levels profoundly matters—and it lauds the organizations and groups that have stepped up to do their part, however small or geographically remote, in helping to create the next generation of women artists.

Actually, highlighting these places was not the only pitch that I made to Sandra: I was going to visit these places, too, during the course of my normal travels between New York and the West Coast. The pandemic and safety will ultimately dictate the recurrence of this column, but thanks to good timing and precautions, I have so far been able to continue my drives back to see family and explore this vast country along the way. It is with great pleasure, then, that I share with you this inaugural article. In it, I write about Sun Valley, a small resort town in Idaho where an admirable museum model for public awareness and discourse has been instituted, and which I visited during my ninth cross-country road trip.

Pathfinding in Sun Valley, Idaho

In conversations about social progressiveness, Idaho is basically always left out. Today considered one of the most conservative states in the country, it would seem like an unlikely place to go searching for an openly supported establishment where strong, creative women can exhibit their art, share their stories, and advocate for change. Yet, in the same way that one can be surprised by the 395,000-acre Craters of the Moon lava field in the middle of the state (I mean, I was surprised by it—and I was out there looking for it), one can be surprised by Sun Valley in Central Idaho (ditto).

Somewhat befittingly, Sun Valley lies not far from the aforementioned geological anomaly. It is located in Blaine County and similarly nestled in a rugged landscape of mountains transitioning into plains. From either Boise or Idaho Falls, a drive takes about 2 hours and 40 minutes via Highway 20—a remote but at times scenic corridor running south of a few national forests through the Snake River Plain. The only city with a population greater than 15,000 in closer proximity is Twin Falls, with a population of a little under 50,000, one hour and 40 minutes away due south. Welcome to rural Idaho.

However, about 20 minutes shy of the final destination, one gets the first hint that what lies ahead is not sparsely inhabited farmland: Friedman Memorial Airport appears on the left, and its runway and terminal make it clear that it is fit for commercial flights. By the time one catches sight of the high-end shops in downtown Ketchum (population: approx. 2,800), one knows that one is dealing with a resort town.

For some, Sun Valley will need no introduction—such is its fabled history and ski resort fame. Officially, it is a city of about 1,500 adjacent to Ketchum, but the name often refers to the region comprising both cities plus the valley extending south past the airport to where the Snake River Plain opens up near Bellevue. I point this out because it is in Ketchum, and not the city of Sun Valley proper, that one finds the Sun Valley Museum of Art.

I became interested in the Sun Valley Museum of Art (SVMoA) when I found out that it had recently mounted an exhibition celebrating the centennial anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. The force of the title—Deeds Not Words: Women Working for Change—suggested that this was neither a token exhibition nor the museum’s first foray into the charged sphere of women’s rights and social equality. Indeed, subsequent research revealed that Deeds Not Words was part of a larger, multidisciplinary program—called BIG IDEA—that sought to deliver on the museum’s commitment to community conversation and engagement. So, off I went with a detour to Sun Valley to learn more.

One of the first things that I noticed upon entering the museum was the portion of wall next to the door listing some BIG IDEA milestones. It proclaimed up at the top, for year 1999, the first two BIG IDEA projects and traveling exhibitions. One of these was Uncovered and Recovered: Women Artists in the Modernist Tradition.

Toward the back of the museum, I found a portion of wall highlighting humanities lecturers who had participated in the programming over the past 50 years. The presence and diversity of women on the list (Joy Harjo, Barbara Ehrenreich, Vicki Ruiz, Gloria Steinem, Mary Oliver—just to name a few) were uplifting, but at this point, I was starting to wonder how this all went together in what was ostensibly an art museum. After receiving the Deeds Not Words brochure from the friendly assistant at the front desk and doing a bit more reading, I reached out to SVMoA’s curator Courtney Gilbert for some answers. Our phone conversation left me truly enthusiastic about the museum’s unconventional approach.

Courtney explained that SVMoA’s exhibitions focus not so much on art history but, rather, work toward the museum’s larger mission of public dialogue. As such, they mostly relate to BIG IDEA projects alongside performing arts and lecture events. These latter two components help to bring people to the museum where they can simultaneously be exposed to conversations that they might not otherwise have in a less multidisciplinary setting. As an example, Courtney mentioned a recent lecture on the brain. Some attendees might have been interested in neuroscience but maybe not so much in art or certain regional or national issues. Nevertheless, these people would have still found themselves surrounded by an art exhibition and thematic project—and hopefully gained more awareness (if not a new interest) in the process.

Then there is the strong pre-K-12 school program that generates interest in the museum among the young, who sometimes later manage to involve their parents. Admission to the museum and parking in the area are free, so even the slightest interest in visiting costs nothing. Random foot traffic is common as a result; the museum is only a block off Main St. I even found myself waiting behind a bus with an ad for SVMoA on the back of it at an intersection. The overwhelming message in all this seemed to be: at least think about what we are presenting.

That message, to me, is crucial. So often when it comes to advocacy, we find ourselves more or less preaching to the choir, again and again. Meanwhile, the greatest (but hardest) gains are usually made by inspiring the need for change among those who are not already thinking about the issue. This predicament thus adds power to the fact that for almost four months, between January 8 and April 16, SVMoA had the Deeds Not Words: Women Working for Change exhibition and BIG IDEA project up for anyone to saunter in and view, free of charge, in a state where social change tends to experience more inertia.

On display was work by five contemporary artists (Pat Boas, Angela Ellsworth, Elena del Rivero, Kim Stringfellow, Lava Thomas) and one early 20th-century architect (Alice Constance Austin), each responding to different aspects of women’s historic struggle for justice and equality. The treatment was not limited to woman suffrage. For example, Thomas’s Mugshot Portraits: Women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott honored specific women who mobilized for basic civil rights for Black Americans, while each pin in Ellsworth’s sculptures draws attention to the countless individual women who worked collectively for dress reform but whose names we will never know.

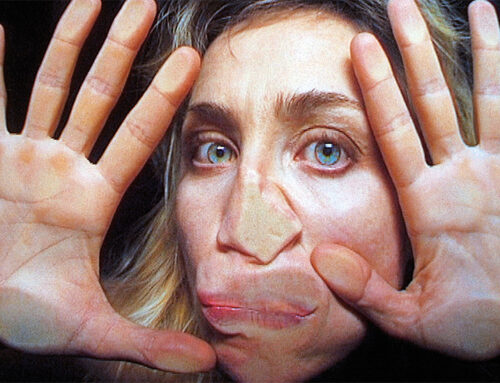

Elena del Rio, image courtesy Sun Valley Museum of Art; photo by Dev Khalsa

For the 50 or so women that Courtney described as working as full-time artists in the valley, the region undoubtedly still presents challenges. The cosmopolitan crowds that come with resort life and help to buoy change only come seasonally—and the same goes for the economic activity that they bring. On this latter point, Courtney said that the museum is very conscious of a financial bias toward male artists, and finding ways of making the art world more equitable and inclusive is always on the museum’s mind.

Alice Constance Austin, Kim Stringfellow, related materials, image courtesy Sun Valley Museum of Art; photo by Dev Khalsa

As it turns out, SVMoA’s status as a non-collecting museum facilitates this. Without a permanent collection to maintain, the museum is able to support a much greater flow of new work and provide visibility for many more women artists. In fact, as curator, Courtney said that she tries to avoid featuring the same artist twice. The museum also occasionally holds workshops for professional development (how to write artist statements and resumes, contact galleries, etc.), enlisting the help of the Idaho Commission on the Arts as needed. While tackling the larger problem of equity and inclusion will take many more institutions, such steps are invaluable for the local women who need to feel supported and optimistic about the viability of their artistic careers.

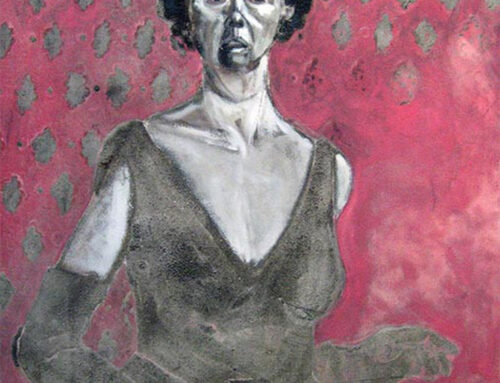

Pat Boas, image courtesy Sun Valley Museum of Art; photo by Dev Khalsa

Lava Thomas, image courtesy Sun Valley Museum of Art; photo by Dev Khalsa

Angela Ellsworth, image courtesy Sun Valley Museum of Art; photo by Dev Khalsa

I cannot write enough about how much I love what the Sun Valley Museum of Art is doing and how I believe its approach addresses certain widespread weaknesses in advocacy. If the first step is always the hardest, then it likely corresponds to the step that gets people through the door of a museum or gallery to view art by women. It is the step that can transform our experiences and voices from nonexistence to reality in the mind of the unaware—and perhaps surprisingly, there is a model for making it happen in the middle of Idaho.

Linh Vivace

www.linhvivace.com

Instagram: @linhvivace