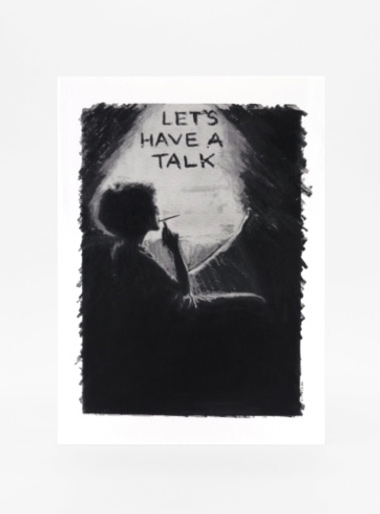

Let’s Have a Talk: Conversations with Women on Arts and Culture

Let’s Have a Talk: Conversations with Women on Arts and Culture

Edited by Lauren O’Neill-Butler

Review by Sandra Bertrand

When I first opened this hefty book of eighty-eight interviews with notable women in arts and culture, I turned to the Table of Contents. The subjects appeared to be in alphabetical order but by first, not last names. A bit confused, I read the introduction, in an attempt to get my bearings on what Lauren O’Neill-Butler intended for the reader. The majority of the interviews were published online in Artforum, which she edited for eleven years. But how to present them?

They are a slippery lot, these subjects. From filmmakers like Agnes Varda, to writers, critics, and gallerists such as Lorrie Moore, Lucy R. Lippard, and Virginia Dwan, to art activists who obliterated the “niceties” in the women’s gaze like Joan Semmel, Carolee Schneeman, Yoko Ono, and so many others, they are all part of the “continuous present”. Quoting Gertrude Stein, the editor chose to present this parade of art practitioners at random. It was a wise choice, because diving willy-nilly into this creative melee, though messy at times, is a marvelous adventure.

About a third of the way in, I discovered Dorothea Rockburne. From her geometric studies in the late sixties to her passion for the mathematics of nature, she has carved out a prodigious art career. Her latest discovery? Stardust. Someone sent her a photograph of a perfect hexagon over Saturn in 2007, which she realized must have been formed by an explosion, releasing particles pushed into shape by electromagnetic currents. A creative mind in process!

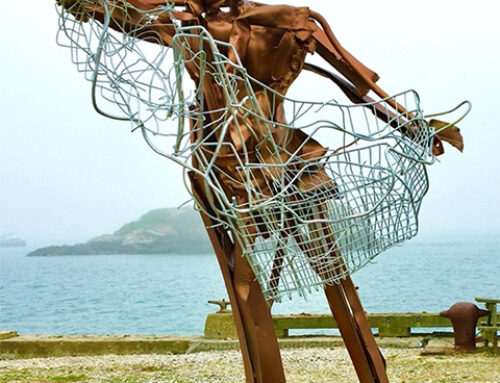

Nature’s discoveries are plentiful right here on earth, evidenced by sculptor Carol Bove. Her solo exhibition at the Horticultural Society of New York in 2009 included an accordion-fold book of a daffodil collection by Janine Lariviere arranged on a timeline according to registration dates. Bove felt the daffodils revealed a “period eye”, meaning certain things can look good at a particular time—an important discovery for Bove. But it wasn’t just popular whim at work that determined, for instance, the taste for brown daffodils in 1973. Daffodils are all clones of one another, so a variety cannot be renewed once it has faltered.

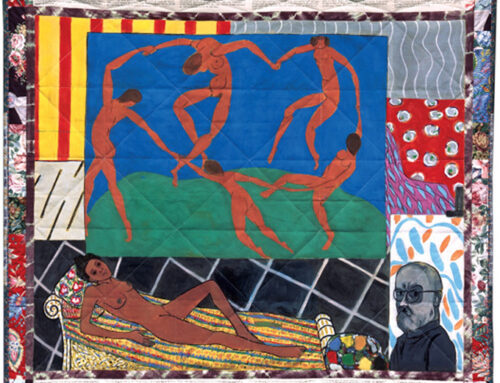

A search for meaning outside the self is often pursued by the creatively-endowed. In Joan Semmel’s case, however, she has spent a five-decade career contesting the history of the nude in art. Vividly-colored canvasses extend from copulating couples to her own aging body. The most convenient model is herself, a constantly changing self. Through this self-regard Semmel aims to change the way the culture views the aging, to liberate women from the constriction and invisibility she has observed in their makeup.

It is only a small leap from the self-obsessed portraiture of Semmel’s palette to the performance art phenomenon that leaped onto the world stage in the sixties. Joan Jonas, inspired by the Living Theatre, Lucinda Childs, and choreographers like Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown, became a pioneer of the discipline. Video art making followed, wanting each of her performances to last. Perhaps the most provocative of these experimental performance artists is Carolee Schneemann. Paintings, dance, installations, films, and videos exploring identity and sexuality were fair game. Dancers became a kind of impersonalized collage material for her. Controversy was her middle name. Such projects as Meat Joy at NYC’s Judson Church, were dismissed by many critics of the day, but in current times reinvented by Lady Gaga with her meat dress performance.

Feminism is writ large in the lives of many of these artists, and Schneeman is no exception. Her observations on what it meant to be a dancer, feminized through the masculine aesthetic, left little room for any deviance. Men would discuss feminism with her and other women artists, but then “it was their ballgame all over again.” Critic Lucy R. Lippard recalls deciding not to talk about feminism anymore, then giving an art talk at MoMA, interrupted when an audience member said “Well, we don’t want to call ourselves feminists.” She spontaneously answered with “That hurts our feelings!” She had to laugh at her response, but it seems the defense of feminism isn’t over, not by a long shot.

Judy Chicago would have to agree. Best known for The Dinner Party, a massive, triangular table set with thirty-nine place settings, each representing an historic female figure has insured her a permanent place in art history. She doesn’t see the struggle being about giving white middle-class career women more rights. She sees it as a “fundamental change on our planet.”

As I said at the start of this review, these interviews were designed to be picked up and perused “at random.” That’s what I did, and I recommend readers to do the same. There’s a lot of “talk” here, some structured and obviously formalized in the editing, and some deeply personal. More importantly, Let’s Have a Talk is a conversation worth having.

(Let’s Have A Talk: Conversations with Women on Art and Culture, published by Karma Books, New York, 2021)