Fern Isabel Coppedge

1883 – 1951

One Woman’s Struggle for Equality in the Art World

By Les and Sue Fox

On July 28,1883, in Cerro Gordo, Kansas, a little girl was born who soon became obsessed with the colors of snow that danced before her eyes. These shifts of color and light in nature so dazzled her that she was called the “yellow, purple and green sheep” of her family. This same girl would grow up to become America’s greatest female winter landscape artist (Grandma Moses notwithstanding). In fact, Fern Isabel Kuns Coppedge may just be, arguably, the country’s greatest female landscape artist period.

Thanks to the exhaustive and loving research of Les and Sue Fox, there should no longer be doubt about the power and lasting beauty of Coppedge’s paintings. As the only female member of the famed New Hope School, she never tired of painting the scenes surrounding her Lumberville, Pennsylvania studio, Boxwood; the Glouster Harbor where she spent many summers; and even the golden light of the Arno River in Florence during a European sojourn. She was a consummate artist, whose works could rival the very best of her contemporaries.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the Foxes left no stone unturned in their obsession to uncover the life works and archival photographs of their favorite artist. From illustrative Kuns Family Tree records, biographies and heirlooms; early wanderings from her schooling in McPherson and Topeka, Kansas; her marriage to Robert Coppedge; to Illinois (the Chicago Art Institute); New York (The Art Student’s League), Gloucester, MA; Philadelphia; Lumberville; and finally New Hope, PA, she followed the winding paths of her artistic calling.

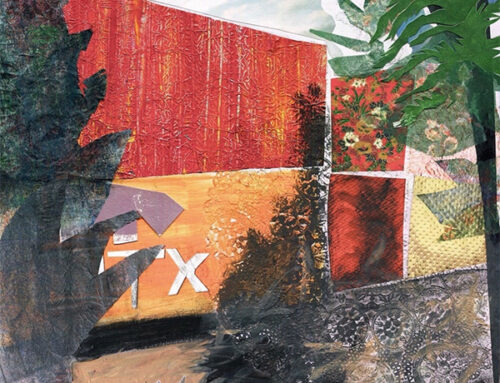

Fern Coppedge, Canal Reflections

Undoubtedly, Fern’s indomitable will was a perfect match for her outsized talent, but her spouse Robert was an unfailing lifelong supporter. He convinced her to leave her studies as a liberal arts major and enroll in a new arts program at Topeka High School, headed by a certain Iris Andrews who was closely associated with renowned artist William Merritt Chase (he later became her instructor at New York’s Arts Student League). A fortuitous decision, not unlike a later choice to spend periods of time apart, where Robert maintained a residence in Philadelphia and Fern built her beloved Boxwood studio home in Lumberville.

We get in-depth glimpses of Fern’s membership in The Philadelphia Ten, founded in 2017 by a group of women artists determined to advance their chances of success independent of the male establishment. Fern also found support with the National Association of Women Artists, then known as The National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. Her painting A Morning in Winter received an Honorable Mention in 1922. Though largely ignored by the male members, through her own persistence and undeniable talents she gained a foothold in the New Hope School. Known as the Pennsylvania Impressionists, they comprised the leading school of American landscape painters during the first two decades of the 20th century, with members such as Daniel Garber and Edward Willis Redfield.

Fern Coppage, January Sunshine

After brazenly suggesting a solo exhibition of her paintings at NYC’s newly constructed Carlyle Hotel, she won the day, garnering greater public attention. A reviewer from the New York Evening Post remarked that “for the particular kind of painter Fern Coppedge happens to be, the absence of snow makes the same difference in the pursuit of her career as the lack of water would make to a swimmer.”

Exhibitions of Coppedge’s work continued to grow, a notable solo held at the Argent Gallery in NYC in 1939, the year of the New York World’s Fair.

Considerable attention is given to the world class retrospective exhibition in 1990 of 51 of the artist’s works at the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, PA. One of a dozen historic prisons to be converted into a museum, it was created to preserve the history of the Delaware Valley and to honor its local artists. “Fern Coppedge: A Forgotten Woman” brought the artist’s genius, though posthumously, to the forefront. Curator Alan Goldstein compared her evolution to Cezanne, van Gogh, and Gauguin, a heady tribute Fern would undoubtedly have enjoyed. A notable exception to her landscape obsession is her oldest known painting, The Dutch Girl, a darkly sensitive portrayal of her subject.

Besides the impressive scholarship evident within these pages, an extra added gift from the Foxes is an imagined interview with the artist over tea on her 50th birthday. A Time Machine Visit with the Artist gives us a closeup encounter in her studio, with a generous, offhand demeanor on display. When asked about a certain painting on display and pleased that the authors like it, she replies: “Good. Unfortunately, it’s not for sale right now. But I’ll let you know if I decide to sell it. How much would you be willing to pay?” A little jostling about price ensues, giving us a hint of the artist’s approach to a possible sale.

The comprehensive catalogue raisonne containing 400 paintings is divided into three major categories: Part I – Winter/Snow Scenes; Part II – Gloucester Harbor Paintings; and Part III – Seasonal Landscapes. One of her winter landscapes, January Sunshine (1930), appeared on the Antique Roadshow in 2007, the owner flabbergasted to discover an appraised value of $120,000 to $180,000. Road to Point Pleasant (circa 1930) and Five O’Clock Train (1933-1934) are only two of many that reveal the artist’s mastery of perspective, the ability to draw the viewer’s eye into the scene at hand. Mechanic Street (1936) is a study in contrasts, with the snowy foreground lined with the boldly cheerful colors she used so well.

The Gloucester Harbor Paintings are another labor of love. She captured perfectly the docks, cottages, sail boats, row boats and the special light of the season and place. Gloucester Harbor (1916-1920) gives full rein to the expansiveness of her view, with full-blown sails catching the harbor breezes. Red Sails in the Sunset (1929) is a serene evocation of the late day light.

Fern Coppage, New England Shore

The Seasonal Landscapes section includes paintings from her early years in Topeka, Kansas as well as her summer study with the Art Students League School in Woodstock, NY, with later Fall images from New Hope and lastly, a sampling of European scenes from her 1925 travels. Canal Reflections (circa 1930) shows a bucolic mirror image of the canal banks. Green and Gold (late 1930s-early 1940s) is an explosion of seasonal color with the palette hues Coppedge knew so well. The Golden Arno (Florence, Italy) (1925) evokes the timelessness she brought to so many of her best works.

We are indebted to the authors and their contributors for making Fern Coppedge an unforgettable American artist for generations to come.

Fern Coppedge 1883 – 1951, One Woman’s Struggle for Equality in the Art World,

By Les and Sue Fox, West Highland Publishing, copyright 2021