Looking Forward

The Life and Art of NAWA President (1961-65) Greta Matson

by Catherine Toulsaly

The National Association Women Artists (NAWA), founded in 1889, counted among its members many immigrants and a few African-American artists. There was a strong social component in works by past NAWA members. Some NAWA artists lived through the Great Depression and times of war; some nurtured opposition to the rise of fascism, militarism and the natural consequence of those movements – war. They, too, heeded a call for nonviolent resistance in the 1960s to shape public consciousness and stir feelings of compassion in their audience.

History has been dismissive of the immense value of the woman artist’s eye and the artworks created in the light of social progress. NAWA President Greta Matson ( served:1961-1965) said, “You can’t have everything. Not a full family life, an art career, and a social life all at once.” It is less about being remembered as one of the “great” American artists than being one out of many — a tessera in a universal mosaic — who provides insight into human nature and contributes to the betterment of our inner humanity.

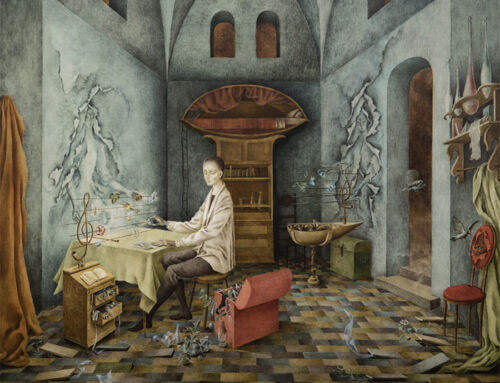

Former President Matson was a celebrated portrait artist. Her talent gained national acclaim in the 1940s. Her journey into artistry was marked by determination and resilience. Growing up in Claremont, Virginia, her interest in painting sparked in high school when she enrolled in an art class. After graduation, Matson sought mentorship under Glenna Latimer and studied for one year at the Grand Central School in New York. Matson spent four summers at Cape Cod, where she studied under Jerry Farnsworth becoming Farnsworth’s class monitor. Early in her career, she engaged actively with NAWA, participating in the annual exhibitions and traveling shows.

Matson was described as an approachable and compassionate woman. She commented that having one’s portrait painted was therapeutic. Often, the subjects felt their portraits represented aspirational goals. She liked to emphasize the eyes, because she felt that a person’s true character and aura shine through the eyes. She expertly captured the essence of individuals during times of grief and hardship, as exemplified by the profoundly empathetic gaze found in artists like Photographer Dorothea Lange. As if her father were emerging from Lange’s photograph, the sensitive depiction of his anguish in the powerful watercolor piece, Grief, exhibited at the 1944 NAWA Annual Exhibition, added a poignant layer to her artistic narrative. He remained a recurring subject and so was her mother, notably in Sewing, which was exhibited at the 1946 NAWA Annual Exhibition.

Parallels could be drawn between her work as a portraitist and French painters Manet and Degas who brought to the forefront a larger concept of portraiture, delving into the narrative possibilities inherent in different societal strata. Post-impressionist realism planted the seed of the artist-citizen. Matson understood the value of her social involvement when she volunteered to sketch soldiers during World War II , and when she did portraits other than those of notable figures such as in Short Order, Looking Forward and Grief.

The year 1961 marked the beginning of a new political era. Matson was elected President of NAWA the same year John F. Kennedy was elected President of the United States. At that time, the Book Review Section of the Sunday New York Times accepted photographs of artworks to publish with its book reviews. Grace Glueck, a former picture researcher, said these photographs were published in the Book Review and Sunday Magazine sections of the Times. Matson’s painting, She will live on her own, illustrated a Times review of Angus Wilson’s novel Late Call and Looking Forward was chosen to illustrate James Baldwin’s essay, A Negro Assays the Negro mood, in the March 12, 1961 edition.

Matson’s work may have been chosen to visually complement the sentiments and ideas conveyed in the book reviews or to enhance readers’ engagement and understanding of the issues. Gender and race (both of the artist and the subject) mattered. A mural study featuring African American women in the workplace (1944) by the African-American artist Thelma Johnson Streat could as well have summed up contemporary sentiments.

The year 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of James Baldwin’s birth. He wrote his essay in the aftermath of the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of The Congo and the ensuing protests on February 15-16, 1961, at the New York headquarters of the United Nations. Matson’s Looking Forward embodies the yearning for a “new day” at home and abroad.

The relevance and evocative nature of Matson’s portrait of a “courageously poised” young African American for which she earned the Ida Wells Stroud Prize Award at the 82nd annual exhibition of the American Watercolor Society (AWS) in 1949 may be evidence of the connections between art and social commentary and underscore the contribution of artists like Matson to the broader dialogue of their time.

Seven years before the AWS award, Matson painted an older and wealthy white woman – in a profile pose turned to the right – titled Looking forward (New Britain Museum of American Art) as if independent of one’s background, we look beyond ourselves to a better future. In 1962, the year following publication of Baldwin’s essay, Matson exhibited at a NAWA show a brush drawing of an elderly white woman turned to her left titled Looking backward.

Matson was praised for her forward-thinking and courage in leading NAWA through four progressive years and numerous impactful projects. For instance, on February 24, 1965, Matson as NAWA President endorsed legislation to establish both the National Endowment of the Arts and the National Endowment of the Humanities within the same year.

On October 16, 1963, Robert Moses, President of the New York World’s Fair, invited Matson to serve on the Board of the Women’s Advisory Council Board to the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, which was intended to represent 265 women’s organizations around the world.

Matson’s NAWA presidency ended the year the United States sent its first combat troops to Vietnam.

Matson’s artworks have vanished from public view. The whereabouts of her pieces, Grief and Looking Forward, are unknown. Only reproductions of images from newspaper stories survive. Photographs for this article were provided by the Chrysler Museum, the New Britain Museum of American Art and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

[1] The Sculptress Augusta Savage took part in the 1935 NAWA Annual Exhibit with Martiniquaise and The Sage, and in the 1937 NAWA Annual Exhibit with Pelican (also in 1936) and Leonora.

[2] Theresa F. Bernstein with Suffrage meeting (1914), Reading the War News (1915), and The Immigrants (1923), Grace Mott Johnson, Marion Greenwood, Hilda Katz, Maria Nunez del Prado, Minna Harkavy with American Miners’Family (1931) and My Children are desolate because the enemy prevailed (1939), Alice Harold Murphy with Man’s Work (1937), Berta Margoulies with Mine Disaster (1942), Margaret Brassler Kane with Harlem Dancers (1937), BlackOut (1939), Air Raid (1942), and Breadline (1989), Lena Gurr with Evening at Home (1948), Miriam Troop with The Two Faces of Hate (1964 Margaret Lowengrund Memorial Prize) and Jan Wunderman with The Human Condition, No.2 (1966 Medal of Honor and the Ernest Holzinger, Ph.D. Memorial Prize).

[3] “So, the nonviolent approach does not immediately change the heart of the oppressor. It first does something to the hearts and souls of those committed to it. It gives them new self-respect; it calls up resources of strength and courage that they did not know they had. Finally, it reaches the opponent and so stirs his conscience that reconciliation becomes a reality” (Martin Luther King J., Pilgrimage to Nonviolence, 1960).

[4] After the birth of her children, a boy named Lance and a girl named Janine, she devoted her time to her family. Her artistic focus centered closer to home, drawing inspiration from her immediate surroundings — family, neighbors, rooftop views, backyard scenes, and even the house across the street (Virginian-Pilot, July 21, 1957).

[5] Ken Johnson, A Long Life Lived in the Shadow of Others, New York Times art review, August 28, 2014.

[6] Matson showcased her artistry through multiple solo exhibitions, notably at Portraits, Inc. In 1943, she held a significant one-woman show at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. At the pinnacle of her career, her work Judy was described by the Richmond Times-Dispatch as a beautifully integrated canvas, a fine example of delicate color arrangement. Wistful, little Judy is communing with the infinite and will continue to do so long after this show is forgotten and her watercolor piece, Woman Sewing, as a mastery of the medium, exhibiting a technical prowess that was more felt than seen. Her artwork Early American was acquired by VMF in April 1943. In 1943, she reportedly won the Hallgarten prize for her portrait of a boy named Pat at the 117th annual exhibition of the National Academy. City Girls was featured among the watercolors exhibited at Gates Memorial Library in Texas in 1945. Her piece titled The Bath (Frick Digital Collections) earned the Altman Prize at the 119th Annual Exhibition at the National Academy of Design in 1945. The Spring Hat won the $350 purchase prize at the Second Annual Art Exhibition at the Indiana State Teachers College and was acquired by the college as part of its permanent collection. The Texas Tech Art Institute acquired her oil painting titled Working Girl at the 23rd circuit exhibition of the Southern States Art League. Portrait received the Atlanta Art Association Portrait Prize at the annual exhibition of the Southern States Art League in 1947. At the Corpus Christi Art Exhibit and Sale, she received an honorable mention for Well Earned Rest in 1948. Short Order clinched the Anna Cogswell Wood Prize of $200 for the finest oil painting in the Irene Leach Memorial’s sixth annual exhibition, in 1948. City Boy, an oil painting, won the purchase award at an art exhibition held at the Indiana State Teachers College. Titled Thoughtful Mood, her watercolor claimed the First Cash Award Prize at the State Teachers College, in 1950. Sad Drinker earned the first prize at the Caller-Times art exhibit and was acquired by the A & I College through donation, now part of Texas A&M University–Kingsville, in 1954.

[7] Despite a discouraging grade of C at the six-week mark, she refused to give up. One of her teachers suggested Matson abandon painting, advising her to get married instead. It only fueled her determination. Her sketchbook became her constant companion. “Talent is of very little importance,” she said. “Perseverance is the thing.”

[8] Despite all of her achievements, Matson’s daughter, Janine, said that her lack of formal education prompted her to return to college later in her life and finish a degree.

[9] Notably, at the 51st NAWA Annual Exhibition, she earned the Mrs. George Eames Barstow Prize of $50 for her black and white piece titled The Jute Worker. Her involvement continued at the 54th Annual Exhibition in 1946, for which she served as an awards juror. By the 58th Annual Exhibition in 1950, Matson played multiple roles within NAWA. This period coincided with her relocation from Norfolk to Brooklyn in New York City, where she resided with her husband, Alfred Khouri. Her talent garnered recognition with the Samuel Krasick Memorial Prize at the 60th Annual Exhibition. Three years later, her painting The Morning Paper clinched the same prize at the Annual Exhibition, now housed in the Chrysler Museum’s collection. Her involvement extended beyond the Annual Exhibition, actively participating in NAWA’s traveling watercolor shows in Santa Fe, the Winona State Teachers College in Minnesota, the Massillon Museum in Ohio, and the Abilene Museum of Fine Arts in Texas.

[10] National Gallery of Art, Dorothea Lange: Seeing People (November 5,2023 to March 31, 2024).

[11] Such as in Sleeping Up. She earned first prize in 1956 for another painting of her father, known as Big Matt, at the Pen and Brush Club’s annual Spring Oil Show, previously displayed at the 1945 NAWA Annual Exhibition (and awarded the John Myers Foundation Prize at the 1963 NAWA Annual Exhibition).

[12] Metropolitan Museum of Art, Manet/Degas, September 24, 2023 to January 7, 2024. “Both artists stretched the definition of portraiture, introducing ambiguities and exploring its narrative possibilities by representing a broad range of people.”

[13] The expression was used by the artist Barnett Newman ((Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965 – 1975, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, March 15 to August 18, 2019).

[14] During the 1940s, Matson taught art classes to servicemen at the Norfolk Navy Yard and the Portsmouth Naval Hospital. With other famous New York artists, she contributed sketches of servicemen through “studio parties,” drawing portraits that were later sent to their families. Approximately 100 sketches were temporarily exhibited and circulated by the American Federation of Arts across the United States. Matson estimated she likely created more than 1,000 sketches for soldiers and sailors in New York and Norfolk, offering her talent as a heartfelt gesture of support.

[15] Among many others, she painted the portraits of the Dean Emeritus of Columbia College Dr. Harry J. Carman (1964), the Dean of the College of Women at the College of William and Mary Dr. Grace Warren Landrum as a gift from the graduating class of 1947, the New York Secretary of the State Caroline K. Simon (1963) and the actress and President of the American National Theatre and Academy Peggy Wood (1961).

[16] New York Times, October 8, 2022.

[17] NAWA Newsletter, May 1962.

[18] New York Times, January 10, 1965. Like the book’s heroine, Matson lost her husband, the artist Alfred Khouri, 47, on July 27, 1962. Their connection stemmed from their time attending Farnsworth’s class in Cape Cod. Alongside her husband, she taught art classes to a new generation of artists in both New York and Norfolk. The couple’s collaborative efforts included managing a cooperative studio group in New York City known as “The Broadway Painters.”

[19] Ryan Murphy from The New York Times Photo and Page Archives said in an email dated October 10, 2023, they have no information about the origin of the 1961 article.

[20] Ink and Graphite on Paper. Thelma Johnson Streat, who was not a NAWA member, became in 1942 the first African-American woman to have a work, Rabbit Man, purchased by the Museum of Modern Art.

[21] See, The Lumumba Plot: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination (Stuart A. Reid, 2023).

[22] Matson’s career trajectory started with watercolors then moved to oil portraiture.

[23] In 1962, NAWA maintained a consistent national presence, circulating three exhibitions—oils, watercolors, and graphics—across the U.S. NAWA fostered cultural exchanges between the United States and foreign countries.