RECONSIDERING CAMILLE CLAUDEL: “WOMAN GENIUS”

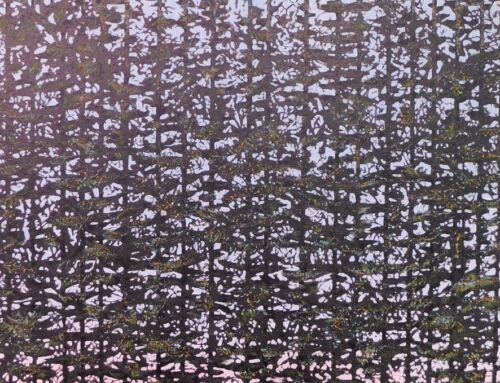

Camille Claudel in her Paris Studio (left), and a portrait of Camille Claudel (right)

by Micheline Klagsbrun, NAWA

“A revolt of nature…a woman genius…”

Critic Octave Mirbeau’s words in 1895 sum up the combination of admiration and condescension that greeted artist Camille Claudel during her early career. Born when ‘woman genius’ was considered a contradiction in terms, she was nevertheless celebrated for her technical skill as a sculptor of the human form. She was also famous (or infamous) as Rodin’s main assistant, muse and lover, and, unfortunately, her tumultuous relationship with him, and her descent into poverty and instability, spending the last 30 years of her life in an insane asylum, have been more remembered than her work.

The recent exhibition Camille Claudel, curated by Emerson Bowyer and Anne-Lise Demas, at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Getty Museum, aims to rectify this situation by turning the focus back onto Claudel’s oeuvre.

Claudel’s Bust of Rodin(1888-89), in the Musée Rodin

Claudel began sculpting as a teenager, showing such promise that her mother was persuaded to move to Paris, in 1881, so that 17-year-old Camille could attend a private art academy. Her mentor, Alfred Boucher, introduced her to Auguste Rodin and from 1884-1893 she worked in Rodin’s studio. He had already recognized her talent and she worked on several of his commissions, including the Gates of Hell and the Burghers of Calais, modelling hands and feet. Since Rodin only modelled in clay and plaster, leaving the enlargement, bronze casting and marble carving of his sculptures to be done by assistants, it is likely that she also worked on marble carving. They were also lovers, and she extracted a “contract” from him promising to use his powerful network of influence to help her in her career, and to marry her. Although he kept (or tried to keep) the first part of his promise, he finally refused to leave his wife and ended the relationship with Claudel.

It is easy to sensationalize the story by assuming that Rodin’s abandonment drove Claudel into a life of poverty and decline, damaging her career and her mental stability, finally landing her in the mental institution. But, in fact, she had produced her own work all along, and in the 1890’s she embarked on a creative new period, finding ways to distance herself from Rodin’s influence and differentiate her work from his. Several of her masterpieces date from this period. Rodin for his part continued to support her efforts from a distance, engaging patrons and commissions, often anonymously, on her behalf. But the art world worshipped him, and sculpture at the time was mostly regarded as the province of men, physically demanding and expensive to produce. Rodin’s success spread to the U.S. in the 1890’s, glorified by critics and prominent collectors. Meanwhile, Claudel, who did show a piece in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, alongside his, was virtually ignored. Alma de Betteville Spreckels, founder of the San Francisco Legion of Honor Museum, amassed a huge collection of Rodin and was the first US purchaser of a piece by Claudel, her portrait bust of Rodin, on view there today.

Not until 1984, when her first retrospective opened at the Musée Rodin in Paris, did the art world “discover” her, and her story was popularized in the sensationalist (and not very factual) biopic starring Isabelle Adjani and Gerard Depardieu. At the time, only four Claudel sculptures were in U.S. museum collections, and even today, there are only 10.

When I stepped into the exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, I had not read the weighty catalog and I did not know much about Claudel’s life. Through my feminist lens, I was prepared to see Claudel as a tragic victim exploited by her powerful teacher. I looked for, and found, evidence that he had stolen at least one creative idea from her. Yet, as I walked through room after room, I was filled with admiration for her work, work that had been unfamiliar to me. I was also deeply impressed by how different most of her work was from that of Rodin. It occurred to me that preoccupation with the victim stereotype could undermine my appreciation of the innovation and boldness of her work.

The relationship that emerges from this exhibition is more nuanced than I expected. It appears to have been truly collaborative, with Claudel learning constantly from Rodin and the mutual sharing of creative ideas and concepts. On the one hand, the example of Rodin’s copying that I had fixed on compares her terracotta Young Girl with a Sheaf (1887) with his Galatea (marble, 1888): the pose of the seated young girls, hand on shoulder, is virtually identical.

Camille Claudel, Young Girl with a Sheaf, terra cotta (1887)

Rodin, Galatea, Marble, 1888

Much has also been made of the fact that two small bronze heads, Head of a Laughing Boy and Head of a Slave, or The Call, were originally stamped with Rodin’s signature; however, the catalog makes it clear that this was a case of mistaken attribution and stamping after Rodin’s death. On the other hand, a closer look at the work reveals that they borrowed from each other and altered those borrowings according to their individual style.

While she was still working in his studio, in 1884-5, Claudel produced Crouching Woman, clearly modelled on Rodin’s earlier Crouching Woman. Rodin’s figure is more defined, especially the head, which is fully visible and bent to the side, and the limbs are arranged in a way that seems almost stylized, like a yoga pose, but with the shocking element of exposed genitalia. To me, it seems designed to show off a striking composition.

By contrast, Claudel’s woman hides her face within her clasped arms: her body is a smooth, sensual pod, containing and concealing her essence. And she took the concept even further by creating a second sculpture, Torso of a Crouching Woman, in which she removed the arms, head and one knee, emphasizing the curving back as a holding element, almost like a protective shell.

Rodin, Crouching Woman, Bronze

Claudel, Crouching Woman

The exhibition culminates in The Waltz, Claudel’s life-size dancers that seem to fill the entire room in which they are displayed, whirling with energy. She produced several versions: in earlier, mostly nude, examples, the sensuality of their embrace balances with its gracefulness. The couple each has one arm firmly placed on the other’s naked body, yet each also has one arm reaching out in an elegant pose. His lips hover over her outstretched neck, yet there is also space between their torsos. It seems like an idealized balance of desire and distance. Armand Dayot, the inspector general of France’s Fine Arts administration, pronounced the work unacceptable for government support due to its “shocking sensuality” and pressured Claudel to clothe the figures. The result is the dizzying flow of whirling drapery evident in the exhibition version. Claudel added bronze lacy “veils” that float in an openwork web around the couple, sheltering, concealing and revealing all at the same time.

Claudel, The Waltz

I couldn’t help comparing this whirlwind to Rodin’s evocation of ideal romance The Kiss, which seems so solid, so static and heavy by comparison, and also so literal, with the two mouths securely melded together. The Waltz, in its continuous spiraling motion, seems to move beyond the material, becoming a flow of energy.

There are many more intriguing examples of the way in which Claudel managed to free herself from Rodin’s influence, taking the techniques she had learned in his studio and using them to create work that was very much her own. One of my favorites in this show is The Chatterboxes, a small group of four nude women huddled together in intimate and animated conversation. It epitomizes the kind of everyday small-scale subject that Rodin disdained and which for Claudel provided a wealth of humanity and emotion. She is even credited with creating a new genre for sculpture with these small private “sketches from nature”. The women in The Chatterboxes are extremely expressive, their faces and body postures lively and timeless.

Claudel, The Chatterboxes

This exhibition is an eye-opener, a feast of powerful, evocative work that is unfamiliar to most audiences in the U.S. (the two previous exhibitions of her work were in 1984, at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC, and at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 2005). There are too many masterpieces to mention here, including The Implorer and The Age of Maturity, in which Claudel seems to comment directly on her relationship with Rodin. I will close with a glimpse of one of her last works, Fortune (1902-4), another version of the female dancer of The Waltz but this time portrayed alone, one foot on her classic wheel. Here, I take issue with the interpretation of Franck Joubert in the exhibition catalog. He writes: “Perched in fragile equilibrium atop her attribute, the wheel, she is now no more than a solitary, blind dancer, herself abandoned to fate.” In contrast, I see an indomitable spirit, still in fluid motion, despite all her tribulations, raising one arm aloft and dancing into the future.

The exhibition Camille Claudel was on view at the Art Institute of Chicago, October 7, 2023, to February 19, 2024, and at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, April 2 to July 22, 2024.

Ed. Note: All references and quotes are taken from the exhibition catalog, Camille Claudel, Getty Publications, 2023.