by Linh Vivace

I will let you in on a little secret: I have committed myself to featuring only one place from each state in this column. This article, then, actually constitutes the article for the state of New York. How did I choose just one community, especially being a New Yorker myself? Needless to say, I started out with a very long list—but from the moment I learned about the Hodinöhsö:ni’ (Haudenosaunee) women in Upstate New York, it became no contest. Not only did I feel that this topic would perfectly conclude the set of articles highlighting various celebrations of the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment (keep reading to find out why), I felt that it was both timely and overdue. Here we have a community of women who have fought for centuries for the authenticity of their identity, dignity, and way of life while the world has changed rapidly—and often hostilely—around them. The most stunning element is how they have managed not to crumble in light of the chasm between their own culture’s attitudes towards women and those of the dominating culture coming from without. As the hard-earned gains of the Women’s Rights Movement are overturned in some cases and increasingly under threat in others, maybe it helps to go back to where it began to see if more can be learned about standing our ground.

Ganondagan State Historic Site, New York; photo by Linh Vivace

PATHFINDING in Ganondagan, New York

Even if you do not know anything about the history of the Women’s Rights Movement, signage in the Finger Lakes region of New York lets you know that the Women’s Rights National Historical Park, a unit of the National Park Service (NPS), is located in Seneca Falls. Visiting on a gray, rainy morning, when the streets were very quiet, I reiterated the question in my head that had kicked off this research: “Really, Seneca Falls?”

Sure, I had known about the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention (more instructively known as the First Women’s Rights Convention) since high school, but recently I had become decidedly dissatisfied with the explanations I had heard about why Seneca Falls was the “Birthplace of Women’s Rights”. The reasons all involved some mention of a reform community emerging in western New York in the 1830s and 1840s, to paraphrase the NPS brochure, but that only begs the question. Why did it emerge? I spent some time in the museum at the Women’s Rights National Historical Park Visitor Center and then sat in on a presentation by one of the park rangers in Wesleyan Chapel—the site where, on July 19 and 20, 1848, about 300 women and men had gathered to hold the first women’s rights convention. Free to all and managed by a federal agency, the Women’s Rights National Historical Park arguably reflects the official historical record regarding the emergence of the women’s rights movement in the United States.

Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, New York; photo by Linh Vivace

Seneca Art & Culture Center, Ganondagan State Historic Site, New York; photos by Linh Vivace

Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women: From the Time of Creation exhibit, Seneca Art & Culture Center; photo by Linh Vivace

However, up until a few years ago, this record did not include the profound connection to the Hodinöhsö:ni’ women nearby. The set of panels presenting that connection there now owes its existence to the conversation started by the Seneca Art & Culture Center at Ganondagan State Historic Site.

Women’s Rights National Historical Park Visitor Center museum, Seneca Falls, New York; photo by Linh Vivace

I had come to Seneca Falls knowing full well that I would be continuing on about thirty-five miles west to Ganondagan, but anyone could have easily overlooked the display or not processed the mention of the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Confederacy in the park ranger’s presentation. This is an enormous pity. It is with this missing piece of the puzzle that a far more complete and satisfying picture emerges about what transpired here—the proverbial “something in the water”. At the very least, it was in the land: Six Nations land.

Ganondagan preserves the site of what was once the largest Seneca village in the 17th century. However, its status as a historic site should not give the impression that it is wholly in the past: the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Confederacy survives to this day, and Ganondagan helps connect Hodinöhsö:ni’ people across the region. The Seneca Art & Culture Center, built in 2015, aids in this community-building while also connecting the Hodinöhsö:ni’ community with the non-Hodinöhsö:ni’ community.

Seneca Art & Culture Center, Ganondagan State Historic Site, New York; photos by Linh Vivace

Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women: From the Time of Creation exhibit, Seneca Art & Culture Center; photo by Linh Vivace

Seneca Art & Culture Center, Ganondagan State Historic Site, New York; photos by Linh Vivace

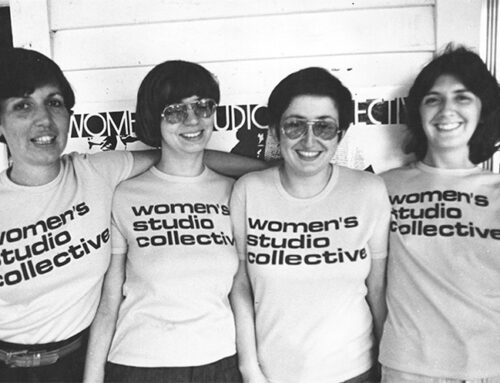

As museums and institutions across the country were planning exhibitions and celebrations honoring the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the Seneca Art & Culture Center mounted an exhibit in 2018 called Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women: From the Time of Creation, doing what the Hodinöhsö:ni’ culture has been doing from time immemorial: honoring its women. The exhibit illuminates the largely ignored existence of the matrilineal Hodinöhsö:ni’ culture, as well as its documented impact on some of the leaders of the Women’s Rights Movement, including Matilda Joselyn Gage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony. From the full ownership of titles, houses, and her own person, to the right to hold council and to forbid her brothers and sons from acts of war, a Hodinöhsö:ni’ woman and clan mother would have held an unimaginable position in her community by European and American standards centuries ago. Indeed, the exhibit can surprise even now—and “now” is what this article is about.

Seneca Art & Culture Center, Ganondagan State Historic Site, New York; photos by Linh Vivace

Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women: From the Time of Creation exhibit, Seneca Art & Culture Center; photo by Linh Vivace

Because as much as I would love to elaborate on this part of history (everyone should read up on it on their own after finishing this article), I would like to point out even more that, as non-Native women’s rights were expanding in this country, Native women’s rights were declining. The result has been that, today, Native women and Native women artists lag in terms of equality and recognition compared to non-Native women by several decades, regardless of what their own cultures may have dictated. Among the current issues are disproportionately high levels of violence towards Native women and unsolved cases of missing Native women; the persistent lack of attribution when it comes to Native women’s work throughout history (the “anonymous” problem); and Native women’s work automatically being deemed “crafts”, rather than “art”. This should obviously all sound very familiar. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) movement and the groundbreaking Hearts of our People: Native Women Artists exhibition have strove to correct this, but the fact that they are fairly recent arrivals to the scene only proves the point.

Hodinöhsö:ni’ artist Tonia Loran (Mohawk – Bear Clan); photo courtesy Tonia Loran

I had the immense pleasure of interviewing several Hodinöhsö:ni’ women—all of them artists—after my visit. I was struck by how lively and full of conviction they all were, despite expressing acute awareness of the stereotypes and injustices against them throughout American history. After all, it is easy to remain buoyant if one has one’s blinders on—but these women are informed and cogent. Tonia Loran, who recently retired from her job at Ganondagan State Historic Site and whose recreation of the wampum belt granting the clan mother the right to lead her clan and the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Confederacy is part of the traveling Hearts of our People exhibition, spoke of the truly dark times when the Seneca and other nations lost their rights while American women were gaining theirs. She readily acknowledged that this has left a tremendous disconnect between the way American culture views Native women and the way Hodinöhsö:ni’ women—and men—view women within their own culture. Until there is a more informed and nuanced understanding of Native women and Native cultures, she recognized there cannot be genuine support. The tricky bit in the case of Hodinöhsö:ni’ culture is that it means admittance of the fact that American culture has been the one with more to learn in terms of women’s rights and equality. This has not been something some people have been willing to do, as some of the reactions to the exhibit and the disbelief and/or anger all of my interviewees have seen from other people at various times in their lives have demonstrated. The exhibit’s reception over the years has been largely positive, but being forced to confront one’s own stereotypes does not always go down well.

Tonia’s daughter, who goes by the name Jojo and is still in school, gave an especially memorable statement of the stereotype she sees represented in the media: that of the “chief giving his daughter away.” To say the least, it is an absurd image to be imposing on a Hodinöhsö:ni’ woman, but Jojo conveyed her criticisms and reflections on the compound discrimination experienced by Native women with a bubbliness that hints at the power of growing up in a culture with a deep, long-standing respect for women: self-assurance in one’s worth. Although she said it was not always easy to establish her own identity, the Hodinöhsö:ni’ ethos of women’s participation in society being a requirement for that society to function properly seemed to leave no doubt that any investment in herself was a worthwhile undertaking.

Samantha Jacobs, who grew up on the reservation and contributed a pair of moccasins to the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women exhibit, likewise exuded a steadfast connection with her Hodinöhsö:ni’ roots, despite now living over 90 minutes away from Ganondagan. She recounted how her experiences growing up in the community had left her with a lifelong feeling of being grounded in it, such that today, she does not find it hard to maintain her sense of identity or authenticity. Instead, her concern is that the community is losing its voice in western New York. As we discussed the influence of the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Confederacy in the time of the suffragists compared to today, it became clear how much the community has been marginalized since then, and Samantha, also a community educator, stressed the importance of the Hodinöhsö:ni’ people working together to inform the greater public that it is still a living, thriving culture.

Seneca Moccasins by Samantha Jacobs, left, and Karonhia:ke (the Sky World) by Natasha Smoke Santiago, right; photo by Linh Vivace

This is the complex atmosphere in which this Native community supports its women and its women artists day in and day out. It rightfully ought to seem like an uphill battle given the historical marginalization of Native peoples, but as my interviewees noted, Hodinöhsö:ni’ women’s art is simply Hodinöhsö:ni’ art—or, more to the point, human art—and has no separation from the Hodinöhsö:ni’ way of life, so at the heart of the respect and dignity conferred to women’s art in the community is the value the community places in itself. The Native Roots Artists Guild, founded in 2010, provides exhibition opportunities and assists with practical aspects such as professional development and networking. Programming at the Seneca Art & Culture Center is also increasingly preparing Hodinöhsö:ni’ artists for viable careers, with an annual juried exhibition already in place and an exhibition featuring young Hodinöhsö:ni’ women’s artwork in the winter of 2023. Michael Galban, the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women exhibit’s curator and now Ganondagan Acting Site Manager, describes these exhibition opportunities as a chance to provide Hodinöhsö:ni’ artists with a professional gallery experience. He mentioned a burgeoning art market in western New York and the Adirondacks but repeated the unique challenges that Native artists face in trying to find patrons beyond the Native community. In particular, a lack of understanding among collectors regarding indigenous art prevents more widespread appreciation and perceptions of value, and there is still a feeling in the Northeast that leaving one’s Native community is almost required to become a “great” artist, unlike in the Southwest where there is already an established balance between local ties and national recognition.

As for the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women exhibit, Michael said that it will be on display in its current form through the end of the year, at which point, it will be taken down and a smaller but permanent exhibit installed in another area of the center. Staff and volunteers at Ganondagan, he remarked, will not allow the exhibit to be removed completely. If visitors had any say in the matter, I would join them. Finishing my trip to Ganondagan with a tour of the Seneca Bark Longhouse and a walk along the Trail of Peace, I had been so humbled by the day’s education. Moreover, if a local community’s unwavering belief in the rights and dignity of women can persevere—in both its men and women, but perhaps most poignantly in its women—despite the injustices and negative messages that so many Native peoples have been subjected to at large, the local community really is the best place to start.

Linh Vivace

www.linhvivace.com

Instagram: @linhvivace