LOUISE NEVELSON

By Sandra Bertrand

Shadow Dance

Jan 17 – Mar 1, 2025

New York

I hope you got to see this gorgeous show at Pace gallery. I’ve seen a lot of Louise Nevelson’s work, but this show presented her work in a way that changed my perceptions of it. First of all, I had never seen her collages and they were fabulous. Although they are a kind of work I haven’t seen from her before, they were immediately recognizable for their elegance, authority, and innovation. There are times she incorporates the backgrounds into the collages and even the frame, and taste.

The placement of the sculptures in groups that played up the repetition elements of the work also gave me new insight into her process. I saw those elements as rhythm, as if they were musical scores in three dimensions.

Here is a link to the show at Pace:

https://www.pacegallery.com/exhibitions/louise-nevelson-shadow-dance/

Behind the Lens with the Women Photographers Collective of the Mid-Hudson Valley

By Sandra Bertrand

“The camera makes you forget you’re there. It’s not like you were hiding but you forget you are just looking so much.” Annie Leibovitz

This disappearing act behind the lens that photographer Annie Leibovitz describes is no easy accomplishment. When I first encountered the work of the Women Photographers Collective of the Mid-Hudson Valley, I knew they all possessed this unique talent. The magic in the images they produce is very real, but they are as well. I found that it is through their persistence, passion and dedicated support for one another that the Collective continues to thrive and exist as an inspiration to women photographer everywhere.

Photographer Kay Kenny initiated the group to counteract the disconnectedness of the COVID-19 pandemic. “I began to organize the Collective on a walk in Thorn Preserve on a winter day in 2020 with two fellow photographers, Meryl Meisler and Jan Nagle. We were all feeling a sense of isolation. I had a Zoom account and was already a member of a photo workshop group that met regularly on Zoom.” By January 2021, a group of nearly twenty members opened their first exhibit at the Lace Mill Gallery in Kingston, New York. In February 2025 they opened another exhibit in New Rochelle, NY at the Vanda Gallery, organized by longtime NAWA member Susan Phillips. (Vanda has been an excellent resource for NAWA artists, sponsoring other NAWA shows in the recent past.)

Here’s an edited sampling of some of the questions I posed to these four members of the Collective that can be found in its entirety in Sanctuary Magazine: https://www.sanctuary-magazine.com/culture-crawl-september-24.html

Gail Albert is a fiction writer and National Book Award finalist who has incorporated her passion for the environment and her spiritual teachings into her images. Maria Fernanda Hubeaut searches for authenticity in life and art, dissolving boundaries between photography and performance art. Susan Phillip’s love of nature is expressed both in her photography and collage. Kelly Sinclair is an avid explorer of all photographic forms, most recently in portraiture of women as they age.

When did you first realize making images could be part of your vision, something only you could see?

GA: My world is filled with specific creatures in constant transition, whether they are trees or rocks, often mysterious, all sacred. The challenge is in creating images that convey to others what I experience.

MFH: As a very shy teenager, photography not only taught me to be present in every shot but also gave me a sense of purpose.

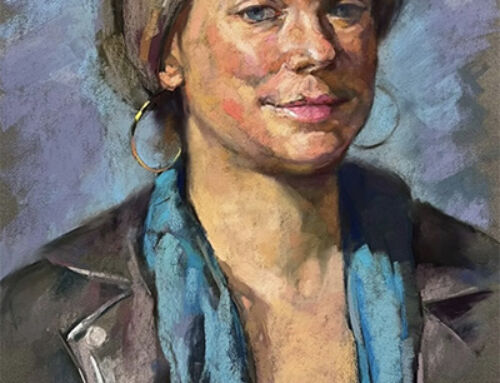

Maria Fernanda Hubeaut, The Dream (El Sueno), The City Object of Meditation Body of Work

SP: After taking what I thought was an excellent shot at the Cloisters in New York City, then developing and printing it myself, I was hooked!

KS: The camera became a bridge between my shy self and the world outside, allowing me to see differently.

Kelly Sinclair, Overlook, Church

Photography can take many forms. Do you see yourself as a street photographer, capturing “the decisive moment” (as photographer Henri Cartier Bresson coined)

GA: I am extremely dependent on the lighting of that ‘decisive moment.’ The objects themselves may not be moving, but the light is always in transition.

Gail Alpert, Morning Frost on Bluestone

MFH: I am deeply inspired by his philosophy that photography is about aligning the eye, the heart, and the camera.

SP I search for art in places often overlooked by people rushing by: street abstractions formed by the effects of traffic and the erosion of painted lines; graffiti art in the visible layers of torn papers, restructured by weather and random anonymous participants; oxidized rusted surfaces creating patterns and designs; reflections in puddles, ponds, or store windows.

Susan Phillips, Abstraction

Susan Phillips, Fifth Avenue

KS: I’ve experimented with many different styles from street photography to landscape and nature to still life. am now venturing into portrait photography, making portraits of women as we age and exploring what this means on a personal as well as a societal level.

Photography as an art form has not always been fully appreciated in the larger art community as “fine” art. In your opinion, how has that changed?

GA: There are galleries that never considered taking photography that now include photography in their open calls. Some galleries now have shows that are only for photography.

MFH: There are still some who do not view it as visual arts. The key is to create from the unique language of photography and to present your work honestly and authentically.

SP: At first, it had to be ‘black and white’ to get into galleries. Eventually, color was accepted. I still believe that the impact of a great black and white photograph can engage the viewer intellectually, in a way that color cannot.

KS: Photography has come a long way since its inception. The art lies in the content as well as the beauty and technical mastery of the photograph.

Creating art can at times be a lonely endeavor. How did you become involved with the Women Photographers Collective, and what are its aims?

GA: I came to photography as an author and psychologist, with no college or graduate courses in photography. I have learned in workshops and internet courses, and by going to museum shows, so I am an outsider. The idea of being part of a group of photographers who share their work was like a light in the dark.

MFH: It’s wonderful to be part of a community of women photographers where we can discuss and share projects.

SP: Everyone’s style and execution vary. Sharing and learning from each other is a singular, enjoyable endeavor.

KS: It’s helping me by igniting my fire to hold myself up to the highest standards. I want to continue to grow and evolve as a photographer.

What has been your experience as a woman, from your early days of learning photography to making it a viable profession, or being accepted within the constraints of exhibitions or public awareness?

GA: I have only been involved professionally in photography in the last ten years. I am not aware of any barrier because of being a woman.

MFH: Photography allows us to infuse our work with the nuanced, empathetic, and deeply personal insights from our experiences as women. Together, we can ensure that the feminine vision in photography remains vibrant, impactful, and indispensable.

SP: Professionally, I was an elementary school teacher for 35 years. I knew that it was my career path. Photography came a few years later and has never left.

KS: The art world has always been dominated by men. But women have always been here, making our art. As we gain more autonomy and agency in society, we are becoming more and more visible, as it should be.

Who are the women photographers who have inspired you?

GA: I have been more inspired by painters than photographers. So, I have to say Georgia O’Keeffe.

MFH: Two incredible, historical women photographers who inspire me are Tina Modotti and Imogen Cunningham, though many others, both past and present, influence my work.

SP: I admire many historical women photographers. Three come to mind. Dorothea Lange was best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration. Lange’s photographs influenced the development of documentary photography and showed the effects of the Great Depression. Berenice Abbott was best known for her iconic photographs of Paris and New York City during the 1920s and 1930s. Her architectural compositions and portraits of cultural figures of that time are realistic and riveting.

KS: So many! Dorothea Lang, Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Orkin, Diane Arbus, Francesca Woodman, Sally Mann, Graciela Iturbide, to name a few.

We are living in challenging times. How do you find peace in your life and art?

GA: As climate change has continued to progress, I have become committed to producing work that emphasizes the sacredness of our planet, encouraging people to act publicly for its protection.

MFH: In times of chaos and uncertainty, it’s natural to feel overwhelmed and distracted. These challenges often fuel my creativity, providing new layers of depth and meaning to my work. I find my own sanctuary in my art.

SP: My photography IS my sanctuary. It helps me to momentarily forget the issues of war, race, environment, elections, etc. It’s just me and the camera.

KS: A friend said to me, when we heal ourselves, we heal the planet. Showing up behind the lens and in front of the lens empowers me and the women I photograph. I find sanctuary or refuge in my life by grabbing my camera and heading into the woods!

Featured South Carolina Chapter Members

By Meyriel Edge, Chapter President

[Ed. Note: South Carolina Chapter President Meyriel Edge interviewed Staci Swider, the Chapter’s Co-Chair for Exhibits, and Saundra Renee Smith for this issue of NOW. The interviews have been edited for clarity].

Photo: Staci Swider with her art, Unapologetic. This work was recently displayed during The Women’s Caucus for Art exhibit, Meeting the Moment, at Aiken Center for the Arts.

MEMBER FEATURE: Staci Swider

Meyriel Edge (ME): Your art includes painting, collage, assemblage, and fiber. How do you describe your art and yourself as an artist?

Staci Swider (SS): As an artist, I identify as a fiber and mixed-media artist because these classifications encompass the majority of my artistic endeavors and provide ample room for creative expression. I approach my work with a highly experimental mindset, relishing the opportunity to utilize materials in unconventional ways. For instance, I delight in juxtaposing rough, unrefined cardboard with the smoothness of Asian jacquard silk, and I find that these unexpected pairings come together seamlessly to create a harmonious composition.

ME: How is your art of today reflective of your past professional career and your family’s ethnic heritage?

SS: During my early years, I worked as a professional fabric designer in both home furnishings and apparel. This experience has greatly influenced my art, as I am naturally drawn to textures and patterns. Even when I use painting and drawing to convey my ideas, I still incorporate patterns and chunky textures reminiscent of the coarse textiles and deconstructed fabrics I remember from the basement of our mill. Our mill had a large garnetting machine that would tear up discontinued fabrics so that the fibers could be repurposed. The texture of the fibers and wool fabric as they made their way through the machine looked like a craggy outcropping covered in soft mist. I particularly love the knobby texture and the look of a destroyed piece of canvas.

In addition to my professional background, my Slavic heritage has also influenced my art. From an early age, I was exposed to Eastern European folk art such as embroidery, lace-adorned garments, and Pysanky eggs. I intentionally refer to these influences first when searching for new design elements for my work.

Photo: Staci Swider presented a solo exhibit, titled “Vessels of the Elder Goddess,” at the

West Gallery of the Summerville, South Carolina Public Works Art Center. “Crone’s Garden,” (above) is a 15-ft-long fiber and mixed media vessel. Swider refers to these vessels in her artwork as “soul sleds” and imagines them to be a place of serenity.

ME: Your art is known for having a feeling of movement. How do you create this sense of movement?

SS: I employ various techniques to convey a sense of movement in my art, including the dynamic use of color, texture, and layering. I often integrate organic forms and flowing lines to lead the viewer’s eye across the canvas. The bold sweeping brushstrokes and varied textures, such as collage materials or patterns, further enhance the perception of motion.

ME: How do you represent yourself within your art?

SS: My narrative compositions, while abstract, evoke a natural rhythm, such as the movement of water or wind, creating an energetic flowing sensation. The interplay of warm and cool colors contributes to the push-and-pull effect, reinforcing the continuous movement within the artwork.

ME: You recently completed an artist residency in Ireland. How did that experience influence your art?

SS: My work focuses on exploring the concept of one’s soul journey. I am fascinated by the mythic idea of one’s daimon, or spiritual companion, who carries our destiny, according to Plato. I refer to the daimon as the “Grandmothers” and wonder how they bear such an important weight both physically and emotionally. How do they manage? Where do they reside? The idea of a boat-shaped vessel gliding effortlessly throughout the cosmos came to me while relaxing in my hammock, and I now refer to these vehicles as “soul sleds.” They are the agents through which the Grandmothers oversee and guide us. With the Grandmothers guiding me, I embarked upon my residency in Ireland in February 2023. It was there, while exploring the countryside of County Kerry, that I came across what is known as “The Greenville Rookery” and was immediately captivated. Hundreds of rooks, large black birds native to Ireland, were swooping, calling, and building nests; nests which reminded me of the soul sleds, suspended high up in the trees. It felt as if the rooks were beckoning me to build and create alongside them. The energy and spirit of that place influenced my art making and will forever remain in my subconscious, regardless of what is present on the canvas.

MEMBER FEATURE: Saundra Renee Smith

saundra-renee-smith-1

Saundra Renee Smith is a Gullah descendent, born in the house she grew up in, on the isolated island of St. Helena, South Carolina. She is a self-taught folk artist or so-called “outsider” who picked up a paint brush for the first time late in life, following the loss of very close family members every six months for two years. “The last to leave me was my beloved mother,” she said. “We laid her to rest on a very cold Christmas Eve morning. I experienced a magnitude of grief.”

ME: Why did you begin painting later in life?

SRS: My husband Michael led me on my path of discovery when he bore witness to my grief. He surprised me one day with canvas of all sizes, paint brushes, an apron, easel, and, most importantly, colorful paints of every hue imaginable. When I applied the first color, cerulean blue, to a brush and struck my first canvas with a wide heavy swath against a stark white background, I felt the artist inside me open new eyes, take its first breath of color and come to life. I painted my way out of the deep dark place of pain, and into a new life of color where my journey brings joy not only to me but to others who also enjoy my work. So “cum en go wid me.” (Geechee for: come and go with me).

ME: What inspires your work and what medium do you prefer for your art?

SRS: My work is inspired by the bright hues born from a culture tempered in isolation. This makes my work authentically Gullah and is a tribute to the people who hold a unique place in American history. The Gullah/Geechee Corridor on the southeast coast of the US is where we thrived and are descendants of the Guale Indians and West African slaves. My medium is acrylic and oil on canvas, wood, tin, or glass. I strive to capture the daily lifestyle of the Gullah people through visual art. Baskets, flowers, water, and sky; women and families with brightly colored dresses; colorful head rags and hats to cover unique nappy hair; and secrets of the land are inspiration for my paintings. My work is spiritual and transformative as I seek to provide a glimpse of Gullah life, and “de luk pon we island” (tr: the look of our island home) through art.

Flowers fa de Fisherman: Gullah Flower Girl

ME: How does your volunteer work mesh with your art?

SRS: I retired in 2016 as a Registered Nurse Educator and hold a doctorate in Spiritual Christian Counseling, a Masters in Administration, and a Bachelor’s

Degree in Nursing. I am the artist-owner of Gullah Art by Renee, LLC on St. Helena Island, and I am grant-writer and secretary for the Saint Helena Gullah Community Housing Project.

ME: Please tell me about the Gullah community.

SRS: The Gullah community on Saint Helena are direct descendants of formerly enslaved African Americans. Homes have been handed down for generations and, although the homeowners own the land, the impoverished Gullah community often needs assistance to maintain their homes. The Project helps by rehabilitating homes and educating owners, tradesmen and women through volunteerism, apprenticeship programs and workshops.

ME: What volunteer work have you done?

SRS: My other community volunteer work includes being the administrator of the Health and Wellness Ministry and Food Bank Program, which led to the establishment of an after school academy. I initiated support to raise funds for a summer recreation camp for island children; developed the HEAL program to address mental health concerns among school-aged girls; supported reopening of a summer camp program; and, developed a Hot Meals Delivery Program in partnership with Beaufort Memorial Hospital and Gullah Grub Restaurant as a life-line for seniors and children. Although challenging at times, I am surrounded by like-minded people who care about our community even though many are not from Saint Helena.

Saundra Renee Smith’s painting hangs on the exterior of a home rehabilitated by the Project.

SRS: My art is a way of showing a community that is without hope that we still care. The art piece is of Matilda Middleton, who died at age 105, and the children who were raised in this house. My hope in creating this art was to restore the memory of the woman who lived there, her legacy in the community, and to restore dignity to our neighbors.”

WOMEN OF THE NINTH: Conquering the Art World

By Jen Haefeli

The Smithsonian Associates recently held a presentation called How the Ninth Street Women Conquered the Art World with Nancy G. Heller. The presentation focused on the book, Ninth Street Women, a chronicle of the events surrounding the Ninth Street Women and their time in the cold-water lofts, by Mary Gabriel, published in 2018.

The Smithsonian Associates recently held a presentation called How the Ninth Street Women Conquered the Art World with Nancy G. Heller. The presentation focused on the book, Ninth Street Women, a chronicle of the events surrounding the Ninth Street Women and their time in the cold-water lofts, by Mary Gabriel, published in 2018.

With nearly a twenty-year age span among them, five of the eleven women who lived in the cold-water lofts represent different chapters in Abstract-Expressionism. Together, Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler launched a postwar American art genre, opening a new door for Modern Art and women. Their time in the cold-water lofts created a movement and made history.

The 1951 Ninth Street Art Exhibition was held in New York’s Greenwich Village. The Ninth Street Women, as they are now known, became the center of the Abstract Expressionist scene, making the new location for post-WWII Abstract Expressionist work The New York School.

Lee Krasner In Her Studio, Source: Kasmin Gallery

As a working female artist, I ask, are we surprised that nothing was sold at the exhibition? If nothing sold, what is it that resulted in this exhibition and the combination of powerful women making history?

What made this different? Was it their dedication to craft? Was it a willingness to leave charmed lives and safety nets, give up the comforts of their lives, not have children, in Hartigan’s case, to decide to have her family raise her child, embrace poverty and vulnerability, and give all in the name of succeeding or living to create? Was it the combination of their unique style? Looking deeper at the connection between these women and their relationships, it seems this was a bit of a lightning strike. Hindsight has the opportunity to reconsider, whereas creating in the here and now, with a strong drive to accomplish something legendary, many of us likely wonder what will make “it” happen. If we want “it”. What is “it” after all, that makes a piece so legendary, and what makes the creator sought after?

John F. Kennedy by Elaine de Kooning, Oil on Canvas, 1963, Source: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Lee Krasner was incredibly talented in photorealism, but her passion was in abstract. Forever connected, however unfairly, to her husband’s work, for a time, she did not create as her work was compared to her husband’s. After Jackson Pollock’s death, she began to create again, and today, she is among the most famous Abstract Expressionists.

Elaine de Kooning’s avant-garde style caught the eye of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, and she was selected to paint his portrait. She became the pinnacle of the New York School of Painters, bringing an appreciation and seriousness to the collection of avant-garde.

Grace Hartigan, a young mother and wife, left her life in the ‘burbs to chase her dream in NYC. She went on to become “The Most Celebrated Woman Painter in America,” as recounted in Life Magazine, 1957. Grace never stuck to one signature style, which likely frustrated galleries and gallerists. She simply created what she wanted to. I get you, Grace.

Joan Mitchell was a Chicago Heiress whose contribution was a large, explosively colorful piece. Her work was expressive and volatile and likely presented her tough exterior, though it may have concealed her vulnerabilities with its bold, visceral, and violent nature.

Joan Mitchell in her Vétheuil studio, 1983. Photograph by Robert Freson, Source: Joan Mitchell Foundation Archives. © Joan Mitchell Foundation

Helen Frankenthaler was considered to be the inventor of “Stain Painting”, a new school of painting she is famous for. Frankenthaler grew up in a prominent New York family and chose the life of an artist.

Each woman came to the cold-water lofts in New York City with her unique background, experiences, interests, and drive. Her work was unique and interesting, and her goals were for her work to succeed and be collected. Each of the artists was talented, hard-working, and self-sacrificial.

Grace Hartigan, Grand Street Brides, 1954, Source: Whitney Museum of American Art

Have we changed over the years? Would we still be willing to forgo motherhood and live somewhat more communally in cold and empty spaces filled primarily with our work? Or have we shifted and ebbed through these past decades? Speaking personally, I have become accustomed to comforts that I yearned to build upon. I was proud as I got older that I could incorporate what I created into my home, and I loved entertaining in my space. I spent my college years visiting artist’s lofts in NYC, where I contemplated the difference between the NYC creative artist’s experience and my own. I often wondered if I was giving up enough of myself for my craft. My immersive creative time was a home studio in my dining room that would spill into my living room with our family pup and our five-year-old watching television and eating breakfast while I worked on a sculpture or painted. Many sewn works over the years likely have small footprints or pieces of our pup’s hair within them. Would this have been different in a loft? Absent of others? Surely, there are aspects of life that are included in one’s work regardless of where one is. Heller was asked how curators and art historians maintain works by Pollock, and a brief discussion was had about the inclusion of Pollock’s cigarette ashes in his work. I rest my case.

Helen Frankenthaler, Source: The New Yorker

Reflecting upon the lifestyle the Ninth Street women kept, they enjoyed a life of letting loose, but it seemed that this happened in an impromptu sort of sense. Perhaps in their studios, amid their work. I envision that their contemporaries gathered among the pieces as they held spirited conversations and critiques flowed. When hangovers set in, perhaps the warmth of a steady brew of cheap coffee throughout the day pushed their work to completion. Living in a studio might be a dream. Maybe the dream held as long as the box of cigarettes. On days a window cold let in the fresh air, I’d venture it was brilliant to be in New York. Cold, rainy days may have been spectacular for working. When the booze, caffeine, and nicotine ran out, and the exhibition loomed, I’d imagine it was a bit of a cold and lonely nightmare. One filled with self-doubt and loud inner voices.

Some modern artists try to balance life differently although aspects of the above methods likely play a role. Some work a day job, and if that day job is to create art, like mine, we work around the schedules of others if we have children. Though I had no plans to become a mother, life can be a slippery slope, and I eventually became Mother Hubbard. I have five. Their artwork fills our home. I can guarantee that, unlike the women of the Ninth, it has been a long time since I’ve settled for something akin to a free packet of ketchup in hot water to make “tomato soup.” It would turn Lord of The Flies very quickly in our home, and regardless of my talents, the household critics would take me down quickly, and the kitchen itself would become much like a Pollock.

Without raising families, the women of the Ninth could move freely in life, pick up work, take custom projects, and work day and night. Though they had relationships, friendships, and family, they poured themselves into their work. It was a commitment they could make themselves. Talent. They had it, but so do many of my contemporaries. Examining the experiences of the women of the Ninth to determine the fundamental aspects of this historical landmark event, I find the work incredible but not unattainable. Legendary, certainly. We owe them a debt of our gratitude. What makes this group different from modern working female artists?

Is it that we want our cake, and we eat it too? Is it that we make our cakes, decorate our cakes, cut them, serve them, throw parties for our families, sit down at the table with them, look around at the decorated house we also keep, and we try to hold space in the moments with our families that we build, and we try to enjoy that cake too? Then after we give everyone their favor bags, we clean it all up, and when everyone has had their time with us, then…we create? I suspect that is the difference between the women of the Ninth and the incredible women who are my contemporaries. That is not to say that all modern female working artists are mothers, but many modern working artists are not in a mindset of living in conditions described in the cold-water lofts. Am I painting with a generalized brush? Sure.

The combination of the loneliness and the darkness amid the hope for success in the lives of the women of the Ninth must have felt overwhelming. It appears that there was a complicated closeness in their relationships. Between sexual promiscuity (not judging!), what seems like rampant drug use (the times were a timing!), a raucous proclivity for parties (huzzah!), and an active flow of alcohol, there was likely a decent cycle of fighting and making up among them.

The legacy these incredible women left is a mark on time, space, and pieces the world may always know. Would I have stepped into their lives and left mine behind? At times, I have wondered what it would be like to have work in a famous museum’s permanent collection, but would I trade the warmth of my life and memories for the emptiness and the darkness of a cold studio filled with canvases yelling to be finished by my tortured mind wondering if giving it all up was the right choice?

Is that side really greener? Perhaps the women of the Ninth have provided us with the question of whether the precedent-setting and indelible mark they’ve made on the art world is worth it. Their wonderful pieces will hold a place in the canon of Post WWII-Abstract Expressionism. Is the price they’ve paid worth their pieces? Are these sacrifices and choices in exchange for respect and recognition for one’s work what we should expect from women? Or can women have this level of career advancement without depression, suicidality, alcoholism, sexual plurality, angst, or the need to abort or avoid motherhood? Did this group of women succeed at that time for a season or a reason? Is this success replicable? Do you have a Lee, an Elaine, a Grace, a Joan, or a Helen in your circle? Look left and look right. Find your “Four Quarters.” If you don’t think that you have them, look again. Empower yourself and do the work to recognize that you are a talented individual surrounded by incredibly inspiring women, and together, we can succeed at what we put our minds to.

I’ll leave you with one more question: who are your Power Women?

[Ed. Note: To explore these five painters and the movement that changed modern art, consider these additional sources the author relied in in part for this article:

https://smithsonianassociates.org/ticketing/attachments/262489/pdf/Ninth-Street-Women-Handout

How the Ninth Street Women Conquered the Art World with Nancy G. Heller

Ninth Street Women, by Mary Gabriel; Little, Brown & Company, © 2018. The book chronicles events surrounding the Ninth Street Women and their time in the cold-water lofts of New York City.

https://npg.si.edu/blog/elaine-de-koonings-jfk

https://www.kasmingallery.com/artists/3-lee-krasner/

https://whitney.org/collection/works/1292

https://www.joanmitchellfoundation.org/joan-mitchell

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/04/12/helen-frankenthaler-and-the-messy-art-of-life