Book Review: The Story of Art Without Men

By Patrice Boyes, Co-Editor

Isaac Newton worked out calculus during a two-year closure of Cambridge University during the plague and transformed physics. Katy Hessel worked out the proverbial “rest of the story” of art during the COVID pandemic and the resulting book “The Story of Art Without Men” (Norton, 2023) promises to be transformative for future students of art history.

Admittedly, I jumped first to the non-linear timeline at the back of Hessel’s 512-page art history book to learn who I had missed 45 years ago in all those art history lectures in college. There appeared many, many talented non-male artists dating from the 12th Century through every recognizable movement in art history — the “Dutch Golden Age”, Renaissance, Edo Period, Cubo-Futurism, Bauhaus, to name a few. Stunned, mildly embarrassed, then feeling a bit cheated, I dug out the musty, formerly trusty 801-page “Art Through the Ages – Fifth Edition (1970)” (all of $13.95 at the college bookstore) and confirmed the absence of any nonmale artists, save Georgia O’Keefe. It was just like Hessel’s experience seeing only one woman artist in “The Story of Art”, a 688-page tome she paged through growing up in her parents’ home in London.

Suddenly, the random and confounding encounters with spectacular, heretofore unknown, nonmale artists’ exhibitions found a context in Hessel’s book. No longer is Swedish artist Hilma af Klint a non sequitur. Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama takes her place among the pantheon of modern multidisciplinary artists. Hessel places British artist Jadé Fadojutimi among the “New Masters” whom she believes will affect the next generation of artists and the future of art history.

Space does not permit discussing all of the significant artists in Hessel’s book, so this review focuses on the new context provided by Hessel for af Klint, Kusama and Fadojutimi.

Hilma af Klint, photo from “Notes and Methods,” University of Chicago Press 2018.

Hilma af Klint

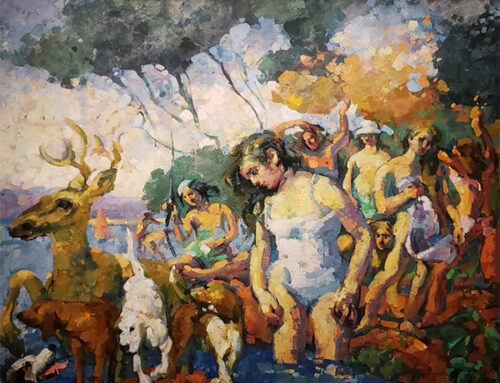

Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) is an artist of the Spiritualism movement, largely led by women, now credited with foreshadowing modernism more than any other movement in Western art. Mediums performed in public and in the home and were said to transmit messages from their spirits in various ways, including creating “automatic” drawings. Artists such as af Klint started using séances as a new method of creating art, according to Hessel. Af Klint drew perspective-free swaths and spirals of color, accompanied by text decoding her symbolism. (The doorstop art history books mentioned above fail to discuss Spiritualism and ignore af Klint).

Swedish artist af Klint was academically trained and produced conventional landscape, portraiture and still life work. But from 1906 to 1920, she produced hundreds of paintings and works on paper, including highly abstracted representational renderings, and nonobjective compositions. She placed an embargo on showing any of her proto-abstract work until 20 years following her death. There was some thought that she believed people would not understand her work until well into the future.

In 2018, the Guggenheim staged a major posthumous retrospective of her work entitled “Hilma af Klint—Paintings for the Future.” More than three meters tall, a number of paintings from the series of 193 works titled, “The Paintings for the Temple, 1906-15,” lined the spiral walls of the Guggenheim. Viewers could also see the influence of science on her thinking and work.

Hilma af Klint show at The Guggenheim, October 12, 2018-April 23, 2019

Hilma af Klint show at The Guggenheim, October 12, 2018-April 23, 2019

Guggenheim Museum and Foundation Director Richard Armstrong said in his Director’s Forward to the exhibition book:

“Her early arrival at abstraction–-before Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and other modernists—is especially notable. From this point of view, her use of a largely nonrepresentational style by 1906 demonstrates not only the depth of her imagination, and it does more than shift a timeline. It occasions an important and timely reevaluation of the emergence of abstraction, bringing to the fore fundamental questions about which factors shaped its formation, how we recount its development, and who is integral to that still-developing narrative.”

Enter Katy Hessel.

Hessel’s book resolves Klint’s place in art history along with those Guggenheim books about the 2018 exhibit and the collection of af Klint’s 124 notebooks holding sketches and photographs of her entire body of work.

Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama (b. 1929) born in Japan to parents who managed a plant factory claimed she experienced hypnotic hallucinations starting in her youth, reports Hessel. Kusama imagined being enveloped by waves of polka dots, nets and flowers. According to Hessel, Kusama emigrated to the Unites States in 1957 after receiving an encouraging letter from Georgia O’Keefe.

Video installation at Louis Vuitton, Paris, July 2023

She settled into the Downtown avant-garde scene. Hessel observes that Kusama placed her repetitive gestures across multiple media, employing strategies to deal with childhood traumas and visions. In one work, Kusama placed sculptures in a boat, photographed it and blew multiple images up as sequentially printed wallpaper – two years before Warhol “created his strikingly, and suspiciously similar, Cow Wallpaper,” wrote Hessel.

More recently, Kusama has undertaken a design collaboration with Louis Vuitton, producing handbag, clothing and even surfboard designs for release in 2022 and 2023. The motifs are her familiar polka dots and pumpkins. Louis Vuitton has erected a colossal statue of Kusama clutching her paint brush and a polka dotted iconic LV Capucines handbag. The statue is located outside of LV’s Paris Head Office near the Pont Neuf.

Hessel lauds Kusama for staying at the forefront of stardom in the art world for seven decades and counting.

Kusama (1963)

Warhol (1965)

Photos (Paris) by Patrice Boyes (2023)

Jadé Fadojutimi

Jadé Fadojutimi

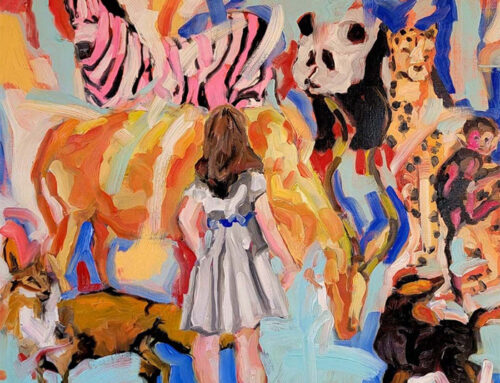

Jadé Fadojutimi (b. 1993) reminds Hessel of the vigor of Joan Mitchell, the expressiveness of Lee Krasner and the luminosity of Helen Frakenthaler, but with a style that is neither abstract nor figurative. “To me, (her paintings) are utopian: worlds where only harmony, joy, and pure colour exist.” They offer language for a new time, she wrote.

“Painting takes me over like witchcraft,” Fadojutimi told The Guardian newspaper.

Having read Hessel’s passage, it is understandable why The Metropolitan Museum of Art included Fadojutimi’s massive work, “Hope” (2021) (Gifted by Tiffany & Co. in 2022), in the chronological layout of its Abstract wing. I encountered the piece in May 2022 as I rounded the corner nearing the end of the Abstract gallery and viscerally reacted, almost tripping. The painting was new but there was no readily available information about the artist. You just sensed this was something fresh and significant.

Hessel has beautifully articulated Fadojutimi’s importance among rising artists. She wrote that Fadojutimi, along with Floria Yukhnovich and Somaya Critchlow, “most directly address the art history that I described to you at the very start of this book. In their work, they are reinvigorating the traditional medium of oil painting, bringing it into the modern day…(they) directly confront contemporary issues and draw from our technology-filled world.”

Jadé Fadojutimi HOPE, 2021 oil, oil bar and acrylic on canvas 220 x 300 cm, 86 5/8 x 118 1/8 in.

Detail from “Hope”

Hessel leaves the reader with hope that retrospectives of overlooked and emerging nonmale artists will continue and noted some permanent shifts. For example, the Baltimore Museum of Art in 2020 only acquired work by women for its permanent collection. In her mind, the future of art is opening up a world without hierarchy.

Much work remains to be done. A study published in 2019 found that in the collections of 18 museums in the U.S., 87% of artworks were by men, and 85% by white artists. In the meantime, readers of Hessel’s book can encourage art educators to consider it in parallel with traditional art history books for a richer, more representative Story of Art.

The Story of Art Without Men was published in 2023 by W.W. Norton & Company. It is available from a number of booksellers and well worth the time to study it.