ETHEL SCHWABACHER: THE EARLY SIXTIES,

AT BERRY CAMPBELL GALLEY

(l) Ethel Schwabacher, Longnook III, 1960, Oil on linen, 87 x 107 inches.

© Estate of Ethel Schwabacher. (r) the artist (ca. 1920s). Both Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

by Susan M. Rostan, MFA, EdD

NAWA Historian

I first encountered Ethel Kremer Schwabacher’s paintings on my iPhone in a momentary flash of images. A reel posted on the Instagram site @nycgalleryopenings offered a glimpse of gestural paintings at Berry Campbell Gallery that connected with my artistic preferences. Investigating the artist who had created the paintings in the 1950s, I found that she had been a historical NAWA member, so I endeavored to know her better and share what I had learned. I had a more recent encounter with the artist’s work when Berry Campbell Gallery opened its second solo exhibition of her works, Ethel Schwabacher: The Early Sixties. Described by the gallery as “a transformative period for the artist,” the paintings on canvas and paper depict a transition from gestural abstractions to more nuanced creations of shapes and colors.

Betty Parsons Gallery had shown many of the paintings in 1962, including Longnook III (1960), the current exhibit’s large-scale (87 x 107 inches) centerpiece. Inspired by her impressions of Longnook Beach, in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, like much of the work, this painting brings the viewer in touch with Ethel’s sweeping broad brushwork over a neutral ground, enhanced with an emphasis on bold, bright shapes of color. With a painter’s eyes, I was drawn into the translucent strokes of vibrant colors forming shapes over a visible grey-tone ground. The immense size of this canvas encourages one to step back to first take in the composition of yellow, orange, pink, white, and blue shapes and the movement around and within the canvas. Moving in to participate in the movement of Ethel’s brush, it wasn’t hard to think about this work as conversations with Cezanne and Gorky about a sense of motion and Matisse about the joy of vibrantly colored shapes.

In The Bride Returns, I and II, the brushy egg-yolk yellows are subdued by their interaction with the gray or enhanced with more opaque layers of variations in the hue. Two greenish ovals turn to each other, not quite touching, separated by a dented triangular yellow-orange shape. Using a similar palette, The Young Wife I, 1961, playfully riffs on “yellow.”

In her journal, Hungry for Light: The Journal of Ethel Schwabacher, edited by her daughter Brenda S. Webster and Judith Emlyn Johnson, Ethel offers her ruminations about Cezanne, Gorky, and Matisse. In her May 29, 1977, journal entry, Ethel reflects on Cezanne’s proclivity for “a slight and delicate motion, as though of breathing.” Cezanne had achieved this illusion by suggesting fluid light surrounding unchanging objects. Schwabacher, too, looked to nature for inspiration, noting on November 25, 1976, “In the country I have enjoyed the unplanned effects of drifting earth and pulverized rock melting one into the other. The rock merges into earth, as it were, and the earth accumulates around the bottom of the rocks, so that there appear to be no lines drawn, but only edges of “matière” meeting as they sift from different directions.”

Continuing that entry on November 25, she turned her attention to Gorky, noting he endeavored to preserve the quality of chance experienced in nature, as when the wind moved portions of the everchanging surface of the earth. Ethel described Gorky painting various layers, “one upon another, and allowing the edge of the underlayer to fringe the overlayer, to appear around it somewhat as an aura, or as giving this same senses of drifting, or fortuitousness, of something happening rather than being made.”

Considering observable changes in nature and aesthetically pleasing observable “differences between adjacent qualities,” on May 16, 1978, Ethel reflects on Matisse’s paintings, “so consistent and there are always lovely spaces that contrast beautifully with one another building to a very satisfying whole, they will not have been as varied as I could have wished. Life itself seemed endlessly varied and even erratic, although what we call erratic may well be simply that which we have not yet understood.” She also noted that Matisee painted pictures “that could be hung in rooms where people lived and wished to live happily, joyously, unplagued by the great problems of the world or its terrible miseries.”

It would be so for Ethel as well, as Patricia Lewy, PhD, author of Interregnum, the exhibition’s catalog essay, comments, “Yet whether working with gesture, geometry, or narration, Schwabacher sought to express her exquisite sensitivity to color and color forms in a visual language that would convert psychic pain –the piercing anguish of personal loss, abandonment, and betrayal – into images of calm, stability, awe, and sheer joy.”

Unburdened by the world outside the gallery, I imagined mixing the colors and their variations in Joyous Knowledge (1961) and applying the paint with my big brushes in The Wooing (1961). Enthralled doesn’t even come close to describing being in those moments.

*Take a tour of the exhibit Ethel Schwabacher: The Early Sixties

GERTRUDE VANDERBILT WHITNEY

Whitney, in Vogue magazine, by Adolf de Meyer, January 15, 1917

by Susan M. Rostan, MFA, EdD

NAWA Historian

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (b. January 9, 1875 – d. April 18, 1942) was an American sculptor, art patron and collector, and founder in 1931 of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. She was a prominent social figure and hostess born into the wealthy Vanderbilt family and married into the Whitney family.

Gertrude Vanderbilt was born on January 9, 1875, in New York City, the second daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II and Allice Claypole Gwynne (1852–1934) and a great-granddaughter of “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, the American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. The Vanderbilt’s first daughter died before Gertrude was born, so she grew up with two older brothers, several younger brothers, and a younger sister. Even as a child, Gertrude chafed at the constraints that her social position and gender imposed, later recalling how she had “longed to be a boy,” comparing her activities with those of her brothers. Growing up, she would record her thoughts and feelings in diaries with arresting candor. She would memorialize her wishes, noting things she could not do just because she was Miss Vanderbilt, longing at times to be someone else and living quietly and happily in a more modest lifestyle.1 The family’s New York City home was an opulent mansion at 742–748 Fifth Avenue, also known as 1 West 57th Street.

John Everett Millais, Gertrude Vanderbilt at age 13, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Growing up, Gertrude spent her summers in Newport, Rhode Island, at The Breakers, the family’s summer home. The family traveled extensively, and Gertrude was educated by private tutors at home and in Europe. Later, she attended the exclusive Brearley School for women students in New York City. Art classes were part of her early education, and she kept small drawings and watercolor paintings in her journals, which were her first signs of the value placed on her early involvement in the arts.

In her youth, Gertrude had a dear friend named Esther, with whom she exchanged letters expressing their deep affection for one another. Esther was the daughter of Richard Morris Hunt, the architect who had built Gertrude’s family home in New York City and summer home in Newport, Rhode Island, as well as many other Vanderbilt mansions. In an era, social environment, and family in which expressions of emotional states were limited, it was with Esther that Gertrude could share her intimate thoughts, feelings, and impulses.2 Her mother, Alice, was so concerned about the friendship that she forbade Gertrude to see Esther. The separation was painful for Gertrude but effective. Esther continued to write heartbroken letters of longing. At the same time, Gertrude had several male beaux until she found the one suitable male with whom she could comfortably share her thoughts and feelings, her neighbor across the Street, Harry Payne Whitney (1872–1930).

Whitney in her studio, ca. 1920

At age 21, on August 25, 1896, she married Harry, a wealthy sportsman, banker, investor, and the son of politician William Collins Whitney and Flora Payne, the daughter of former Ohio Senator Henry B. Payne, and sister to a Standard Oil Company magnate. Harry Whitney would inherit a fortune in oil and tobacco and interests in banking. In New York, the couple lived in townhouses originally belonging to William Whitney, first at 2 East 57th St., across the Street from Gertrude’s parents, and after William Whitney’s death, at 871 Fifth Avenue. Looking to add her personal aesthetic to her décor, she encountered the artist John La Farge and found great pleasure in the artist’s milieu. Taking an interest in American art, she began acquiring work. Within seven years, Gertrude and Harry Whitney had three children: Flora Payne Whitney (1897–1986), Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney (1899–1992), and Barbara Whitney (1903–1983).

The traditional life of a socialite and art collector did not satisfy Gertrude’s long-dormant personal needs. Her marriage had lost its energy, problems intensifying with her third pregnancy, which had triggered a lingering postpartum depression. Sinking into despair, Harry kept his distance, and Gertrude was correct in her suspicions that he was having an affair. While visiting Europe in the early 1900s, she was attracted to the burgeoning art world of Montmartre and Montparnasse in France. Despite her husband’s lack of support and with her mother’s initial encouragement, Gertrude began her sculpture studies. Finding solace and a purpose in her work, she would note in her diary, “I pity, I pity above all that class of people who have no necessity to work. They have fallen from the world of action and feeling into a state of immobility and unrest.” 1

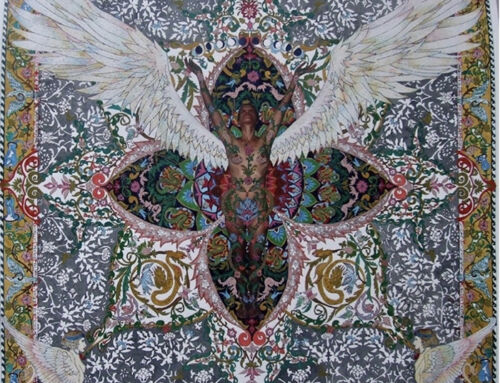

Whitney, Aspiration, entrance to the New York State Building, 1901

She studied at the Art Students League of New York with Hendrik Christian Andersen and James Earle Fraser. Other women students in her classes included Malvina Hoffman (NAWA 1914). In Paris, she studied with Andrew O’Connor and received criticism from Auguste Rodin. Her training with sculptors of public monuments influenced her later direction.

Her first public commission was Aspiration, a life-size male nude in plaster, which appeared outside the New York State Building at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, in 1901. Initially, she worked under an assumed name, fearing that she would be portrayed as a socialite and that her work would not be taken seriously.3 She once told an artist friend, “Never expect Harry to take your work seriously … It never has made any difference to him that I feel as I do about art and it never will (except as a source of annoyance).”4 She believed that a man would have been respected as an artist and that her wealth put her in a lose-lose situation: criticized if she took commissions because other artists were more needy but blamed for undercutting the market for other artists if she did not ask for payment. When people tactlessly asked her why she worked when she did not have to, Gertrude replied that she worked for the pure selfish joy of working. 5

Initially, Gertrude created a studio on her estate in Old Westbury, Long Island. By 1903, she had also acquired space in Manhattan, first on Fortieth Street, then at 19 MacDougal Alley in Greenwich Village. When she moved to the Village in 1907, she joined a thriving group of artists, many of whom were colleagues from the Art Students League. By 1908, Gertrude established an apartment and studio on West Eighth Street in Greenwich Village. After moving her work to Greenwich Village, Gertrude noted that her long problematic shyness had lessened. She was suddenly happier meeting like-minded people with big personalities, as if she had entered a secret society.6

The Three Graces, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Gertrude’s studio environment was a perfect setting for satisfying sexual fantasies and exploring the consequences of her marital indifferences. She engaged in several affairs, and by 1906, she was in a passionate flirtation with the painter Robert Chanler, a member of the Astor and Dudley-Winthrop families. Harry was civilized when he came across a cache of incriminating letters from another paramour in 1919, yet he noted that he had trusted and believed in her. Nonetheless, when Gertrude found herself in Greenwich Village, she and Harry led increasingly separate lives.

She also set up a studio in Passy, a fashionable Parisian neighborhood in the XVI arrondissement. Artists like Robert Henri and Jo Davidson showcased their works there.7 Her great wealth allowed her to become a patron of the arts. Still, she also devoted herself to the advancement of women in art, supporting and exhibiting in women-only shows and ensuring that mixed shows included women. Gertrude began exhibiting her work publicly under her own name in 1910. Paganisme Immortel, a statue of a young girl sitting on a rock with outstretched arms next to a male figure, was shown at the 1910 National Academy of Design. Gertrude’s Spanish Peasant was accepted at the Paris Salon in 1911.

Titanic Memorial I, Washington, D.C.

In 1914, Gertrude established the Whitney Studio Club at 147 West 4th Street as an artists’ club where young artists could meet, talk, and exhibit their works. She provided many nearby housing and stipends for living costs at home and abroad.

The same year, her name appeared in the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors’ catalog when she won the National Arts Club prize for her fountain intended for the Arlington Hotel in Washington, D.C. When funding to build the hotel fell through, Gertrude’s caryatid figure, also known as The Three Graces, was exhibited at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915 (In 1931, a version of the sculpture was installed at Montreal’s McGill University in Quebec, Canada). Gertrude’s Aztec Fountain was awarded a bronze medal in the San Francisco exhibition and her first solo show occurred in New York City the following year.

Critics consider Whitney’s Titanic Memorial, built from a $50,000 prize from a competition she won in 1914, the most important achievement in her artistic career.8

Gertrude’s younger brother, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, perished in the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915. Subsequently, during World War I, Gertrude Whitney dedicated much of her time and money to various relief efforts, establishing and maintaining a fully operational hospital for wounded soldiers in Juilly, northwest of Paris in France. While at this hospital, Whitney made drawings of the soldiers, which became plans for her memorials in New York City. Before the war, she had a much less realistic style, but with this work, realism offered a more profound feeling.9 She completed a series of smaller pieces depicting soldiers in wartime, but they were not seen as particularly significant during her lifetime.

The 1918 National Association for Women Painters and Sculptors catalog listed Gertrude as a member of the “Committee for Awards.”10 The Whitney Studio Club expanded again when its headquarters moved from West Fourth Street to West Eighth Street in 1923, growing in size and scope of programming. In addition to participating in shows with other artists, Whitney held several solo exhibitions during her career. These included a show in 1923 of her wartime sculptures at her Eighth Street Studio in November 1919 at the Art Institute of Chicago. Most of her works during this period were made in her studio in Paris. During the 1920s, her works received critical acclaim in Europe and the United States, particularly her monumental works. During the 1930s, the popularity of monumental pieces declined.

Gertrude donated money to the Society of Independent Artists, founded in 1917 to promote artists who deviated from academic norms. She actively bought works from new artists, including the Ashcan School, and in 1922, she financed the publication of The Arts magazine to prevent its closing.11 She was the primary financial backer for the “International Composer’s Guild,” an organization created to promote modern music performance.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Mother and Child from Knoedler Gallery 1936 exhibit.

In 1929, Whitney offered the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art the donation of her twenty-five-year collection of nearly 700 American modern artworks and enough money to build a wing to accommodate these works. When the Museum declined her offer because it would not take American art, Gertrude established the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Harry Whitney died of pneumonia in 1930 at age 58, leaving his widow an estate valued at $72 million. The following year, Gertrude had architect Auguste L. Noel convert the three row houses at 8–12 West 8th Street into the Museum’s first home and her residence. Whitney appointed Juliana Force, her assistant since 1914, to be the Museum’s first director. The Museum aimed to embrace modernism, shifting away from the notions that American art was largely rural and narrow in scope.

Spirit of Flight by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney at the New York World’s Fair, circa 1940. Archives of American Art.

Gertrude continued her membership in the National Association of Women Artists and Painters till her death, notably participating in the 1932 annual exhibition, which, under the directorship of President Berta Briggs, held the exhibition at the American Fine Arts Building at 215 West 57th Street, home to The Art Students League. The sculptures in that exhibition were in the Vanderbilt Gallery on the first floor, a space named for Gertrude’s cousin, George Washington Vanderbilt II.

In 1934, she was at the center of a highly publicized court battle with her brother Reginald’s widow, Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt, for custody of her ten-year-old niece, Gloria Vanderbilt. Gertrude won custody of her niece.

Gertrude had a solo exhibition at the Knoedler Gallery in New York City in 1936, exhibiting Woman and Child. Two of her last public art pieces were the Spirit of Flight, created for the New York World’s Fair of 1939, and the Peter Stuyvesant Monument in New York City.

Gertrude Whitney died of a heart condition on April 18, 1942, at age 67, and was interred next to her husband in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City. Upon her death, the Whitney Museum of American Art was cleared of the debt it owed her and granted $2.5 million of her estate.

Peter Stuyvesant Monument in New York City.

The Whitney Museum of American Art held a commemorative show of her works in 1943. Her daughter, Flora Whitney Miller, assumed her mother’s duties as head of the Whitney Museum, in turn succeeded by her daughter, Flora Miller Biddle. In 1954, the Museum moved uptown to new quarters on West 54th Street, and in 1963, the Whitney moved to a Marcel Breuer-designed building on Madison Avenue at 75th Street until 2014. Whitney’s current building at 99 Gansevoort Street opened on May 1, 2015, and this spring is celebrating its 10th anniversary at this location.

Whitney’s Greenwich Village studio has been named a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, giving it landmark status.

Sources

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/gertrude-vanderbilt-whitney-papers

10 https://archives.libraries.rutgers.edu/repositories/11/resources/362

Accessed March 19, 2025.

https://archive.org/details/memorialexhibiti00whit

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/gertrude-vanderbilt-whitney

https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/whitney-gertrude-vanderbilt-1875-1942

1,2Friedman, B.H., Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Doubleday and Company New York, 1978

3,4,5,6McCarthy, Kathleen D. (1991). Women’s culture : American philanthropy and art, 1830–1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780226555843. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

7Whitney Museum of American Art (1937). Whitney Museum of American Art: history, purpose and activities, with a complete list of works in its permanent collection to June, 1937. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art. p. 3. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

8,9,11https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gertrude_Vanderbilt_Whitney#Influence_in_art. Retrieved March16,2025.