Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake

NAWA President 1928-1930

Research by Alexa Miller

[Editor’s Note: This is the inaugural installment of an occasional series of articles based on historical research of past NAWA presidents and other NAWA notables]

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake (1894-1981) was a Manhattan portrait painter and arts administrator. She was President of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors from 1928-1930. She remained a member of the American Federation of Arts, the Barnard Club, the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (today NAWA), and the Tiffany Foundation during her career (3), not to mention multiple organizations within Columbia and the Manhattan area.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake (1894-1981) was a Manhattan portrait painter and arts administrator. She was President of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors from 1928-1930. She remained a member of the American Federation of Arts, the Barnard Club, the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (today NAWA), and the Tiffany Foundation during her career (3), not to mention multiple organizations within Columbia and the Manhattan area.

When was she born, and where did she grow up? Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake was born in New York City on December 31, 1894, to Henry S. Stanton and Julia Elliott Colbath Stanton. Unrelated to her namesake, Julia Stanton admired Elizabeth Cady Stanton and named her daughter after the famous suffragist. After her father died in 1906, her family moved to New Hampshire (2) .and a few years later to Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts. The artist J. Alden Weir was a family friend, and Elizabeth recalled sitting on his knee as a child while summering in Windom, MA (4). Her childhood relationship with Weir contributed to her later fondness for his Impressionist work. Blake finished her primary education in Jamaica Plain and was forced to forego college due to poor health. Instead, she enrolled at the Knox School, a finishing school in New York, where she discovered her passion for the arts (2).

When and how did she come to know that she was an artist? How did her education help her in her development as an artist? Blake’s first art teacher was William Chase, an instructor at the Knox School. She noted that studying under him was “what really got her interested in painting.” Grace Noxon, also a teacher at Knox, deeply admired Chase, and Blake noted that both teachers inspired her. Arguably the combination helped spark Blake’s discovery of the arts and helped lay the groundwork for her identity as an artist. Blake later studied with George Bridgeman at the Art Students League. She described him as “the leading authority on anatomy, an interesting man, but not an artistic nature at all” (4). She explained that many students found Bridgeman to be a strict instructor. He was fond of her and would hang her exceptional drawings in a particular place.

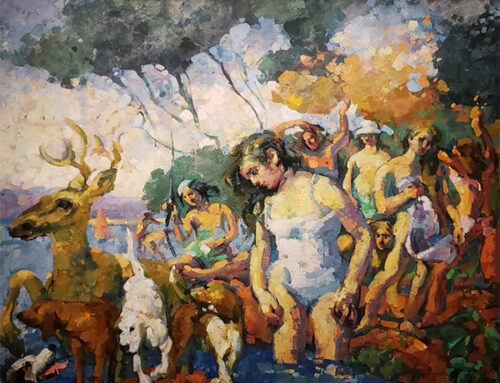

How did she develop her art skills? Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake received her foundational art education at the Art Students League. Her skills primarily developed from taking extensive notes while Cecilia Beaux and Luis F. Mora individually taught The Portrait Class. Painting throughout the length of the class, she noted visible differences in their artistic and technical styles, as well as in their teaching styles. Beaux’s technique was thinking about gestures for a long time, mixing colors and never touching them, whereas Luis Mora would draw things with the background and then build up (4). Blake noted that Luis Mora’s method appealed to her as an artist because she felt she lacked the intellectual depth to sit and think about her gestures for hours before putting them down on the canvas. Beaux emphasized having your vision and believed it wasn’t good for everyone to do the same technique. Speaking about Blake, Beaux said she could “recognize Blake’s work anywhere because of its individuality” (4).

How did she develop her art skills? Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake received her foundational art education at the Art Students League. Her skills primarily developed from taking extensive notes while Cecilia Beaux and Luis F. Mora individually taught The Portrait Class. Painting throughout the length of the class, she noted visible differences in their artistic and technical styles, as well as in their teaching styles. Beaux’s technique was thinking about gestures for a long time, mixing colors and never touching them, whereas Luis Mora would draw things with the background and then build up (4). Blake noted that Luis Mora’s method appealed to her as an artist because she felt she lacked the intellectual depth to sit and think about her gestures for hours before putting them down on the canvas. Beaux emphasized having your vision and believed it wasn’t good for everyone to do the same technique. Speaking about Blake, Beaux said she could “recognize Blake’s work anywhere because of its individuality” (4).

At that time, women and men were separated into two different life-drawing classes at the League. Blake recalls a story from Luis F. Mora, who became her lifelong friend, that a young female model posed only for women, infuriating the men at the time (4).

Blake attended a series of lectures while studying at the Art Students League. One of the lecturers was J. Alden Weir, whom she knew from childhood and continued to hold in high regard. She noted, “He said that in this age, it was necessary to form ideas on a healthy and sane basis. Discrimination, construction, important.” While these lecturers became significant in the development of Blake’s art education, she emphasized that her only meaningful teachers at the League were Albert Sterner and Luis Mora (4).

Which, if any, art trends inspired her work? Did she have direct mentorship? Arguably, her direct mentor, Cecilia Beaux, had a closer influence on Blake than any current art movement of the time. After finishing at the League, Blake’s goal was to study under portrait painter Cecilia Beaux. Blake wrote a letter to Cecilia expressing her disappointment that she was no longer teaching at the Philadelphia Academy of Art and wanted to study under her, asking if she took private students. Beaux did not have private students but offered to meet with Blake in New York and advise her (4).

Expecting to receive Beaux’s mentorship, Blake formed a group, took a sublease on a studio, and collected her equipment, including stools and easels. Blake eventually convinced Beaux to come out of retirement for this class (1), and Beaux began coming to the studio to offer her critiques to the group of students who became known as “The Portrait Class.”(4).

Cecilia Beaux taught the Portrait Class in an unorthodox style. She did not believe in direct teaching, instead using a more passive approach through criticism. Blake surreptitiously took notes of her teaching methods, “Train the eye to recognize and catch the finest and most characteristic pose of the sitter and place it to best advantage on the canvas,” she noted, capturing Cecilia Beaux’s teaching portraiture (4).

The Portrait Class was held at the Gainsborough Studios from 1918 to 1927 (1), with socialites accounting for most students, as tuition costs around $250. Beaux left after one year to complete a series of war portraits in France, and Blake took over instruction as director and manager. Blake moved her studio to the National Arts Building with the help of Charles Robert Patterson, a marine painter, who had a studio there.

Art trends inspired Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake during the early 1900s. Blake noted that she participated in the 1913 Armory Show, a defining moment marking the beginning of Impressionism in the United States (4). Blake’s main painting focus, portraiture, was inspired by the work of her mentor, Cecilia Beaux. Beaux had an “extraordinary” technique of using vibrant colors to create highlights and shadows, leading Blake towards a more Impressionistic painting style. Beaux held firm views on color theory in portrait painting, influencing Blake’s use of cobalt blue and burnt orange in shadow areas, creating a more vibrant contrast. Members of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (today NAWA), such as Jane Peterson, a colleague of Blake’s, had a modern Impressionist style to her early 1900s work. The Impressionist Mary Cassatt, another organization member, appears to have influenced Blake’s work as well.

How did her work change over time? How would you describe her work/process? Arguably, much of her confidence in herself as an artist stemmed from the sought-after approval of Cecilia Beaux. Confusingly, Cecilia told Blake that she “should marry and have children, you would make a nice mother,” (4) implying that she would never become an outstanding artist. After spending many years working together in the Portrait Class, Beaux told her, “You have developed an individual painting style of your own. I wish I could paint red hair as good as you do; I’d always know your work anywhere, Betty, because it’s become very individual.” Through years of criticism and with a begrudging attitude about working together initially, Cecilia eventually admired Blake and her work as an artist. Individuality was Cecilia’s most valued trait in artists, and by the end of their careers working together, she had finally acknowledged that Blake had made herself a successful artist.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Weller Pottery dominated the ceramics industry and, by 1905, was considered the country’s largest mass producer of pottery (5). Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake designed a few pieces for the Eocean line of pottery, which reached the height of its popularity by 1904. Eocean Rose Vase with portrait of Border Collie is one of the series of Eocean vases that Blake created (6). This series circulated in 1905, when Weller was at the height of its career, and Eocean vases were in high demand. The vases were made of earthenware, fired in the kiln, painted, and glazed. They contained a series of animal portraits, with imagery of various dog breeds and a portrait of a kitten. Blake completed the series in her early 20s, marking them as the first pieces of professional work she created and establishing her as a professional artist, creating work for a large company and a portrait painter. The work’s value appreciated after 1948 when Essex Wire Corporation acquired a controlling share and closed the Weller business.

Blake’s career remained focused on portrait painting, with many of her pieces exhibited in the annual exhibitions of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. Little information is available about The Blue Vase, a pastel drawing currently listed in an online auction (6). While the date of this pastel drawing is unknown, it can be inferred that it was made during the early days of her membership at the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. Much of the other members’ artwork then included still-life works, and Blake noted that Jane Peterson “did beautiful flower work” (4). Blake’s experimentation with still-life drawing indicates her arrangement of work as an artist.

Blake’s work is traditional, given her preference for portraiture. Her mentor, Cecilia Beaux, also a portraitist, gave groundbreaking stylistic feedback. Blake felt it was “disconcerting” to her to have worked with both Cecilia Beaux and Luis Mora because they varied greatly in their teaching methods. Beaux gave distant criticism, whereas Mora would demonstrate the technique. “I perhaps didn’t have a strong enough character myself to develop my way of doing things, and I was sort of continually torn between these two different viewpoints” (4).

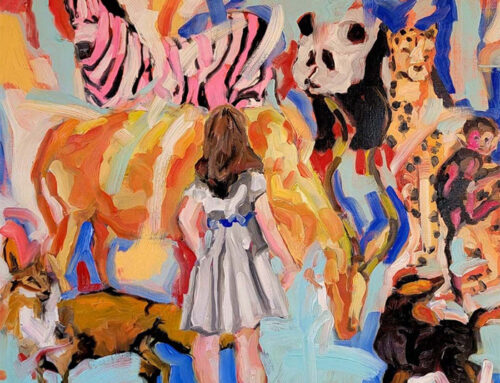

Inspired by the work of Cecilia Beaux, The Dancer was featured at the 1930 Annual Exhibition under the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. It has been exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Women’s International Art Club of London, and a traveling exhibition sponsored by the Rotary Clubs of the United States (9).

Can you describe the materials she used and how they came into her practice? Blake worked mainly in oil, as did other portrait painters of the time. Blake discusses first being introduced to charcoal by George Bridgeman at the Art Students League (4), who was very fond of her work in this medium. She gives Luis Mora credit for introducing her to pastel at the Art Students League.

Where did she find inspiration? Blake found inspiration in portrait painting largely from the people in her life. She created a portrait of Ernest I. Ingersoll, the explorer, a friend of a famous musician she knew, but most of her portraits were of children (4). After a board meeting at the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, Blake spoke with Emily Nichols Hatch, the current president at the time. Hatch wanted to share a studio in Paris, and they did so for a short time, both painting portraits.

One of Blake’s colleagues, Frances de Forest Stewart, lived near the Tiffany estate on Long Island and encouraged Blake to become a foundation member when they began accepting women as members (4). Blake sent examples of her work to Tiffany Studios and was accepted to the foundation after mentioning her affiliation with Frances. Mr. Tiffany invited Blake and her husband, William, to stay at the estate for a weekend so Elizabeth could paint. Impressed by the property’s beauty, she drew inspiration from the hanging gardens and the colored glass that decorated the estate. Louis Comfort Tiffany had a rule that did not allow figure painting, which upended Blake’s main painting style but allowed her to experiment with different subject matter.

Did she have a network of other artists, and how did they support her? Blake was in conversation with many artists at the time through her membership at the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. While working in Paris with Emily Nichols Hatch, she met and worked alongside other American artists (4). They became acquainted with Laura Knight, a famous English painter. Hatch was acquainted with people from the Opera, and Monsieur LeRoux took them behind the scenes of the Opera house, which left a lasting impression on her.

Blake kept a diary for several years, documenting a network of people she met at a reception hosted by Cecilia Beaux at the International Art Congress (4). The entry, dated April 1, 1922, mentions a few artists who attended the reception, including Henry Rittenberg, who lived in the Gainsborough studios and later painted a portrait of Elizabeth. Jane Peterson also attended the reception.

Did other interests influence her art? Alongside art, Blake was interested in sports, music, reading, theater, and Opera (7). In high school, her teachers thought she had a contralto voice and believed she was “opera material.” Blake’s mother was acquainted with the Boston philanthropist George W. Brown, who was interested in having Blake audition for the Opera. He would send her to Europe to study if her voice was promising. The experts found that Blake did not have enough breath control to study abroad. While in Paris, Blake and Hatch took singing lessons with Carl Warford (4).

While Elizabeth was deemed not talented enough to make it as an opera singer, her interest in music remained as she attended many concerts with Cecilia Beaux. She recalls Cecilia had season tickets to the Philadelphia Orchestra and would frequently go together.

Blake moved into Columbia University housing shortly after marrying William, a faculty member in the English Department. Interested in serving the community and working for an institution, Blake became one of the charter members of the Gift Shop at Columbia, which primarily contained gifts for the home. Blake and the Columbia wives worked in the same building with the Red Cross folding bandages and knitting sweaters and socks during World War II (4).

Elizabeth was also involved with Teacher’s College at Columbia. She started TC Day to promote friendly relations between Teacher’s College and the university. Artists attending Teachers College would visit her home and meet Columbia professors there. TC Day aided in easing prejudice against female professors, who made up the larger population of instructors at Teacher’s College.

Elizabeth remained a Columbia University Women’s Faculty Club member, the Columbia Committee for Community Service, and many other campus groups and activities (2). In the broader community, she helped with outreach to less fortunate children through her active participation with the Manhattanville Community Centers, which gave these children a safe place outside of school and enriched their studies (2).

How did she manage a work-life-volunteer balance as an artist? Elizabeth met William Harold Blake in the spring of 1925 when their high school English teacher, who had taught them ten years apart, invited the pair to see her off on a trip to England (2). Elizabeth and William found they had much in common with their family histories but were opposite in temperament (2). Elizabeth had just begun branching out into the art world when she met William and did not personally approve of “a woman marrying and carrying on her career” (4). She noted: “I was not for women’s lib in spite of the Elizabeth Cady Stanton name.” Elizabeth went to Paris with Emily Nichols Hatch shortly after meeting Bill to engross herself with painting before settling down.

The Old Actor was featured in the 1926-27 Annual Exhibition under the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, held at the National Arts Club. The portrait has also been exhibited at the Columbia Club, the National Academy Gallery, and the Women’s Faculty Club of Columbia University (10).

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake, The Old Actor Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Professor Elizabeth MacDowell

Elizabeth and William Harold Blake were married on March 26, 1927. The couple had one child, a daughter, Bettina Blake, born in 1929. Elizabeth tried painting for a little after her daughter was born, but she never wanted to “be a mediocre painter” (4) and did not want to continue painting if she could not be “tops.” After a short while, she became very unhappy with her work. Now married, Elizabeth felt obligated to forgo directing her professional portrait classes and painting. When the Depression era began, Elizabeth and William continued to be very active on Columbia’s campus while raising Bettina. Elizabeth remained involved on campus and in the community after Bill’s retirement in 1952 and his death in 1965. She remained an active volunteer until the 1970s, when her age made it too difficult to continue.

The Old Actor was featured in the 1926-27 Annual Exhibition under the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, held at the National Arts Club. The portrait has also been exhibited at the Columbia Club, the National Academy Gallery, and the Women’s Faculty Club of Columbia University (10).

Professor Elizabeth MacDowell was featured in the 1932 Annual Exhibition under the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. Professor MacDowell was head of the speech department of Columbia’s Teachers College. This painting was widely exhibited and featured in The New York Times (11).

What were her goals as president? Can you talk about how she accomplished these goals, or if she didn’t, what kind of obstacles did she face? Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake became president of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors in 1928. During her time as president, the organization owned a clubhouse at 17 East 62nd Street. Her goal was to sell the space, as it was costly, could not be advertised, and was restricted, so members could not use it. She was disturbed by the $10,000 debt in the organization and wanted to sell it to pay off their debts. Elizabeth persuaded the board then and eventually received an offer that paid off their debt, redeemed bonds, and generated sufficient surplus in their revenue. The organization walked away from the sale with $30,000, one of the last boom prices in New York City real estate before the stock market crashed (8).

In May 1930, Blake bought and built The Argent Galleries on 57th Street near Carnegie Hall. A past president of the organization, Berta N. Briggs, noted in her mission statement in the 1930 Annual Catalog, “The new Argent Galleries embody the spirit of the Association in providing an attractive and adequate place where the painting and sculpture of its members from all over the United States can be shown in the art buying center of New York City,” (9). The new location became the center of art action in the 1930s and 40s, which allowed the Galleries to do well.

Elizabeth also worked with Mary Beard while she was on the board, organizing archives of women’s work and organizations that were women-founded (4). Mary was very disturbed by the lack of women’s records in Washington. While Elizabeth was on the board of the association, she supplied Beard with records, including when and why it was founded and what they were doing to make it possible for women to exhibit in New York. Together, they donated this information to the Smithsonian Archives of American Artists in Washington. One issue Elizabeth faced was that women’s work at the time was not well regarded, especially nationally. Some women could be recognized if they became academicians, but most were not. Elizabeth noted: “They were not properly represented, I mean nationally, and so our national association gave them the chance to exhibit, which otherwise they would have had to have one-man shows, and they couldn’t always support that” (4).

How did the era during her presidency influence the women artists of NAWA at the time? Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake became the first NAWA past president to be made a permanent board member in 1964. She is responsible for the initial expansion of NAWA’s archival collection to Washington, DC, housing archives of women’s artwork in the 1920s and 30s. Elizabeth became a member of the organization in 1923 and also served as Corresponding Secretary, Chairman of the Catalogue Committee, and served on the Exhibition and Program Committees before becoming president in 1928. Following her presidency, she served as First Vice President and, for years after, served on the advisory board, finance committee, attendance committee, constitution, and by-laws committee, and as treasurer for many years. Elizabeth had pieces in the annual exhibitions beginning in 1924 until she stopped submitting her work in 1937.

While president, Elizabeth persuaded Cecilia Beaux to exhibit at the NAWA annual, and she was given the distinction of being an honorary member (4). Cecilia did not initially recognize the importance of the organization. However, Elizabeth proved its significance in helping women who needed a chance to exhibit but could not afford solo exhibitions. At the time of Elizabeth’s presidency, it was the only organization to send exhibitions of women’s art to San Francisco, Cuba, and internationally.

The New York Times covered the Annual Exhibitions extensively in the 1920s. Elizabeth noted that the organization was progressing in a more modern direction people enjoyed viewing (4). The organization founded to allow women to showcase their work lost some of its membership as it became possible for women to exhibit with men. In her 1975 interview with Kitty Gellhorn, Blake acknowledged that some people do not regard the importance of an all-woman’s association because everything has become more coeducational. She noted: “But on the other hand, they feel that today women need all the support they can get, and by sending these exhibitions all over the USA & Europe & South America and we had so many international exhibitions, we were providing a wide showing of women’s work,” (4).

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake died on November 24, 1981, and is buried in Agawam Cemetery in Wareham, Massachusetts.

Today, an award given by NAWA bears her name, entitled the Elizabeth Stanton Blake Medal of Honor Award. Her daughter, Bettina, established this award using income from the estate that her mother passed on to her. In an interview with Jill Cliffer Baratta, Bettina referred to her mother’s sale of the Associations’ clubhouse, noting: “My mother Betty Stanton was not only a professional portrait painter (E.C. Stanton) but a knowledgeable investor, having been trained by Mr. Barron (of Barrons Weekly) himself,” (8).

A collection of Ms. Blake’s written correspondence, The Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake Papers 1915-1975, is housed at the Smithsonian in the Archives of American Art. Donated by her daughter Bettina Blake in 1987, The Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake Papers 1915-1975 contains correspondence, material related to The Portrait Class taught by Cecilia Beaux and Luis F. Mora, an interview of Blake by Kitty Gellhorn, printed material, and a mixed media scrapbook (1). There is also an extensive collection housed at Columbia University entitled, The Elizabeth Blake Papers 1940-2010, which contains her personal papers and records of the groups she was affiliated with at the university and the greater Manhattan area (2). Her daughter also donated this, which contains miscellaneous newspaper clippings, two sheets of Columbia University commemorative postage stamps, and small booklets related to Columbia’s 1954 Bicentennial and lectures given at the university (2).

Sources:

(1) Josefson, Jayna M. “A Finding Aid to the Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake Papers, 1915-1975, in the Archives of American Art.” siris, 11 August 2020, https://sirismm.si.edu/EADpdfs/AAA.blakeliz.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2023.

(2) Arthur, Linda. “Elizabeth Blake Papers, 1940-2010, bulk 1940-1976 | Columbia University Archives | Columbia University Libraries Finding Aids.” Columbia University Finding Aids, January 2014, https://findingaids.library.columbia.edu/ead/nnc-ua/ldpd_10721276. Accessed 20 July 2023.

(3) “Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Cady_Stanton_Blake. Accessed 18 July 2023.

(4) Gellhorn, Kitty, et al. “Mrs. William H. Blake.” dlc.library.columbia.edu, Microfilming Corporation of America, 1979, https://dlc.library.columbia.edu/catalog/cul:tx95x69rdm/bytestreams/access/content.pdf. Accessed 21 July 2023.

(5) Sicard, Jacques. “Weller Pottery.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weller_Pottery. Accessed 08 August 2023.

(6) Hindman. “The Blue Vase.” invaluable.com, Milwaukee Fall Auction by Hindman, 6 November 2015, https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/elizabeth-stanton-american-b-1894-the-blue-vase-210-c-7df44558d9. Accessed 08 August 2023.

(7) World Biographical Encyclopedia, Inc. “Elizabeth Stanton Blake.” prabook.com, 2 October 2022, https://prabook.com/web/elizabeth_stanton.blake/816205. Accessed 18 July 2023.

(8) National Association of Women Artists. “Letters.” National Association of Women Artists, 16 May 2021, https://thenawa.org/letters-6/. Accessed 09 August 2023.

(9) Argent Galleries of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, Exhibition of Members’ Work, May 1st to 30th, 1930. Retrieved from https://doi.org/doi:10.7282/t3-se4w-kd21

(10) Thirty-Sixth Annual Exhibition, National Association Women Painters and Sculptors, 1926-1927. Retrieved from https://doi.org/doi:10.7282/t3-0ghw-n384

(11) Forty-First Annual Exhibition, National Association Women Painters and Sculptors, 1932. Retrieved from https://doi.org/doi:10.7282/t3-c3qj-2481

About the author

Alexa Miller, a NAWA Summer Intern, is entering her junior year at Cornell University. A Fine Arts major with a minor in Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, she worked with the NAWA Historical Research Project co-leader, NAWA Signature Member Susan Rostan. Signature member and PR Chair Mary Ahern created the project in 2023 and co-leads the team.

* The Article was edited in March 2025 after receiving more accurate information from Rona Wilk, PhD and Dr. Bettina Blake, the daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake.

Acknowledgments:

Many thanks for the generous assistance Kate Van Riper, Archivist for Women Artists’ Collections, Special Collections, and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries provided.

Send question and comments to:

magazine@thenawa.org