EXHIBITION: MARY CASSATT AT WORK

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco: Legion of Honor

October 5, 2024 to January 26, 2025

By Micheline Klagsbrun

Lydia at her Tapestry Frame, Print

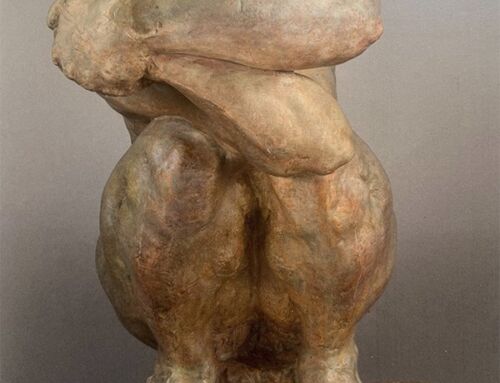

Several recent museum exhibitions have sought to re-evaluate the work and legacies of women artists, for example, CAMILLE CLAUDEL (The Art Institute of Chicago & The Getty Center, 2023-2024)(see companion article in this issue) and Now You See Us: WOMEN ARTISTS IN BRITAIN 1520-1920 (Tate Britain 2024). MARY CASSATT AT WORK is part of this movement, presenting Cassatt “as a fiercely professional artist and an aesthetically radical painter, pastelist and printmaker who helped shape the French Impressionist movement and transformed the course of modern art”.

”Work” in the title refers both to Cassatt’s subject matter – the “women’s work” of caretaking, nursing, bathing – and also to her own intense and professional labor and process. The show focusses on her daring exploration of different media, comparing her use of painting, pastel and printmaking. One could argue that part of her originality as an artist in the world of men is that she took both domestic work and art-making seriously – both types of work are repetitive, hands-on and all-consuming labors of love.

Her domestic subject matter has made it easy for critics to dismiss her as a “serious” artist. But to quote organizing curator Emily A. Beeny, Chief Curator of the Legion of Honor:

“In a sense, the mother-and-child theme was to Cassatt’s final decades what water lilies were to Monet’s or apples to Cezanne’s. Because this motif is and was so freighted with gendered meaning, it’s been too easy to write these pictures off as sweet or sentimental, when in fact they’re formally rigorous, engaged in an ever-deepening conversation with tradition and an ever more experimental handling of paint”.

Maternal Caress, Oil on Canvas

Mary Cassatt studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before traveling to Europe and settling in Paris, showing work at the official French Salon. As her style became more radical, she accepted an invitation from her mentor Edgar Degas to join the Impressionists, becoming the first American to exhibit with them in 1879. Closer to home, and of special interest to us at NAWA, she also exhibited with NAWA in New York in 1892, 1894 and 1896, and lent her name to our organization.

As an additional treat, visitors to the San Francisco Legion of Honor can now view the recently acquired Portrait of Bianca degli Utili Maselli and Her Children by Lavinia Fontana (Italian, 1552-1614), one of the greatest women artists in early modern Europe.

Portrait of Bianca degli Utili Maselli and Her Children

This extraordinary painting has been in private hands for 400 years and is on public view for the first time. Fontana was known for her compelling portraits including dazzling treatment of rich textiles, delicate lace and gleaming jewelry, as well as tender naturalism in her approach to children. She bore 11 children, of whom three survived. Her subject, Bianca degli Utili Maselli, bore 19 children before dying from complications of childbirth. The six children depicted in the painting are likely the only ones who survived. As Emily A. Beeny observes:

“It opens a window onto the life of a Roman noblewoman and her family, marked by both privilege and grief”.

Mary Cassatt at Work was organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in collaboration with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

KATHE KOLLWITZ – The People’s Artist

By Sandra Bertrand

Small Self Portrait, lithographic crayon and ink on paper

“It is my duty to voice the

sufferings of men, the never-ending

sufferings heaped mountain high.”

Born in the Prussian city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia) in 1867, Käthe Kollwitz established herself in an art world dominated by men by developing an aesthetic vision centered on women and the working class.

Self Portrait en Face, Crayon and pen Lithograph

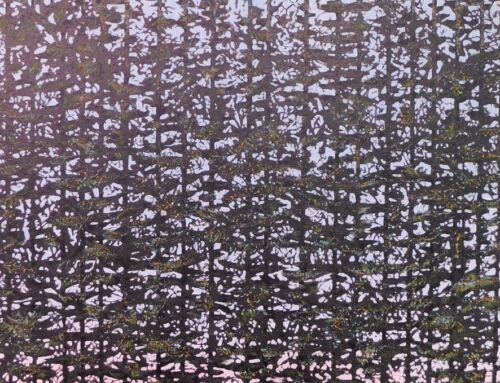

MOMA has chosen to put its long overdue gaze on this extraordinary artist. The 2024 exhibition includes approximately 120 drawings, prints, and sculptures drawn from public and private collections in North America and Europe. Examples of the artist’s most iconic projects showcase her political engagement, while preparatory studies and working proofs highlight her intensive, ever-searching creative process.

An unflinching eye on her fellow man, woman and child is everywhere evident. But what is particularly impressive is the absolute honesty she exhibits in her own self-portraiture, uncompromising in revealing the ravages of time to her face. The question of ego never seems prevalent (or even relevant) to the artist’s aim.

Käthe Kollwitz. The Mothers (Mütter). 1918. Line etching, sandpaper, needle bundle, and soft ground with the imprint of laid paper overworked with black ink, opaque white, charcoal, and pencil. Plate: 9 5/8 x 12 1/2″ (24.5 x 31.8 cm); sheet 12 5/8 x 16 5/16″ (32 x 41.4 cm). Collection Ute Kahl, Cologne. Fuis Photographie.

Following WWI, democracy was on the horizon and Kollwitz became a professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts. It wasn’t until 1932 that she signed a petition encouraging the political left to unify against the Nazi Party and within a year, she was forced to resign. Threats of concentration camp imprisonment grew to a fever pitch. Two weeks before the end of WWII, she died in exile in Maritzburg, Germany.

Art’s role in portraying the human cost in such devastating times becomes more important than ever. Kathe Kollwitz was the artist and woman to do just that, and she succeeded for all time.